There are at least seven powerful reasons to read Pulitzer Prize winner William Taubman’s Gorbachev: His Life And Times (W.W. Norton & Company). It is described by America’s late-Cold War Ambassador to the USSR, Jack F. Matlock, Jr, as “Comprehensive, judicious, utterly absorbing. William Taubman’s Gorbachev: His Life and Times gives us rare insight into the man who changed his country and world politics. A model of careful research and compelling narrative skill, this biography is destined to become a modern classic.”

First, this book often reads like a Robert Ludlum thriller. Bonus: as Henry Kissinger famously said in another context, “It has the added advantage of being true.”

Second, it lays out in vivid terms the formerly secret, thereafter obscure, historical events that very much shaped the world we live in today. Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” If you don’t fancy reruns and would rather avoid watching reruns of the Cold War, here you go. Notwithstanding the subtitle, this book is very much about our life and times.

Third, the events recited in this book preceded — in a perverse way, arguably created the context for — the Putin era. Understanding that context makes it easier to understand our world today. It implicitly provides subtle clues as to how our world might be transformed again.

Fourth, as Churchill famously said in a 1939 radio address, “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in mystery inside an enigma; but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.” Taubman (yet again) reprises Champollion’s role in deciphering the Egyptian hieroglyphics helping us read the riddle of the Russians. Ancient Egypt is long gone. The Russians seem to turn up on page one often. Good to decrypt their code.

Fifth, Gorbachev reveals the story of a political leader in mortal combat with a massive bureaucracy. For those of us following the struggle between our current president and what is romantically, if wrongheadedly, called the “Deep State,” there are profound lessons to be learned. By the way, speaking as one who has served therein, the “Deep State” gives the bureaucracy way too much mystique. Its main weapon is inertia, not laser death rays.

Sixth, Russia and America have an endless love-hate relationship. It verges on the mystical. A better mutual understanding will go a long way toward enhancing the love and subtracting the hate. Full disclosure, I am as passionate a Russophile as I was passionately anti Soviet. It is a great pity that our relationship with our old WWII ally is distorted by a belfry full of imaginary hobgoblins. For those who would like to take a peek at the counter-narrative, see here and here. (Even better, read Taubman.)

Seventh, socialism and communism reportedly are making at least a sentimental resurgence among our dear millennials. I sympathize with their disgust with the economic stagnation our political leaders have imposed upon America for a generation. That said, the stagnation came from an abdication of free market economics, not adherence thereto.

It would be a very healthy thing for our youth to be reminded of what a grotesque thing Communism, and even socialism, proved in practice, especially in its marquee incarnation: the USSR.

Taubman’s masterful work traces Gorbachev from his provincial roots to his rise as a Soviet apparatchik to becoming a regional party chairman. It shows how he was elevated by Brezhnev to the Politburo. After the deaths of Brezhnev, Andropov (of whom Gorbachev was a protégé), and Chernenko, the shrewd Gorbachev vaulted himself into the position of paramount – yet deeply constrained – leader of the USSR. We learn how he attempted to modernize — even civilize — the Soviet Union. There follows Gorbachev’s virulent and enigmatic fight with Yeltsin. Yeltsin would end up effectively Gorbachev’s successor, first president of the Russian Federation. Taubman provides a long and thoughtful look at the aftermath.

For the benefit of those mesmerized by the resurgence of the “Communist Mystique,” consider Taubman on one of Gorbachev’s closest friends at Moscow University:

“It was my five-year stay in Moscow [in the early 1950s] that gave rise to my first serious ideological doubts.” He refused to trace them to “the wretched living standards of the Soviet people, to the poverty and backwardness of their everyday lives. The problem was not chiefly the fact that Moscow was a huge village of wooden cottages, that people scarcely had enough to eat, that the most typical dress, even then, five years after the war, was old military war-issue uniforms, that most families lived in one room, that instead of flush toilets there was only an opening leading to a drain pipe, that both in the student residences and on the street people blew their noses into their hands, that what you didn’t hang onto tightly would be stolen from you in a crowd, that drunks lay unconscious in the street and could be dead for all the passers-by knew or cared.” … [Gorbachev’s friend] didn’t blame Communism for all this, but saw it as “a direct consequence of the war and if the terrible backwardness of czarist Russia.”

Yes, one can always find ways to rationalize and exonerate the object of one’s obsession. Communism to blame? Pshaw!

Yet, fast forward several decades and several Communist Party secretaries (from Stalin to Khrushchev to Brezhnev to Andropov to Chernenko to… Gorbachev himself). Gorbachev, then both leader and captive of the Soviet state, observed after Chernobyl: how there were only about half as many vegetables for sale in Moscow as needed and how many rotted away in antiquated warehouses; how anonymous denunciations remained a plague on society; how (anticipating Donald Trump) the bureaucracy meant “We’re sitting in a swamp”; how almost all economists favored change but have nothing to offer; how the defense industries were in great shape but people had to wait 10-15 years for housing; how the USSR produces more harvester combines than any other country but none of them work; how the Soviet prison population had blown up by a factor of 10 from czarist days; how the whole energy establishment “is dominated by servility, bootlicking, cliquishness, and persecution of those who think differently, by putting on a good show, by personal connections and clans….”

And how the USSR was polluting the environment.

Taubman presents the Chernobyl disaster and its aftermath as a turning point:

[Gorbachev] spent his time planning a drastic overhaul in party personnel, but kept worrying that new cadres would be crippled by the old system. “What was really needed as a real change in the system,” he thought, surprised that “such a conclusion no longer seemed seditious to me.”

Just say’n.

Bernie bros take note.

Taubman defines the transformations in the USSR under its respective supreme leaders succinctly and elegantly:

Ever since Lenin, the Bolsheviks had viewed world politics as a class struggle projected onto the global stage. Soviet Russia represented the exploited of the earth. The capitalist, imperialist powers were Moscow’s sworn enemies. Stalin saw the world as divided into two camps with conflict between the inevitable and enduring peace impossible. In Stalin’s time, the imperialist camp seemed more powerful, but the Soviet camp had important advantages. It could play on “contradictions” among imperialist powers, attempting to divide if not conquer them. It could urge on the working class in capitalist countries, if not to seize power, then to resist anti-Soviet aggression by their rulers. After Stalin’s death, his dog-eat-dog view of the world underwent important but limited, modifications. Khrushchev transformed “peaceful coexistence” from a short-term tactic into a long-run strategy. But his attempt to ease the cold war helped to trigger its two most dangerous crises, in Berlin and Cuba. Brezhnev succeeded where Khrushchev had not by negotiating East-West détente in the 1970s. But absent a fundamental rethinking of Soviet goals and a corresponding reduction in Western alarm about “the Soviet threat,” détente soon gave way to the renewed high tension that Gorbachev inherited.

Even before March 1985, Gorbachev arrived at two new postulates, which Grachev formulates as follows—that the Soviet Union was “clearly losing the competition with its historic capitalist rivals,” economically, technologically, and in living standards, and that contrary to Soviet propaganda’s image of a monolithic, aggressive West, “the so-called ‘imperialist world’ represented a complex reality of different states and societies” and “apparently was in no way preparing to attack or invade the Soviet Union.”

Thus do narratives change. And, in certain ways, Gorbachev’s greatest achievement, and greatest legacy, may have been in fundamentally changing the narrative of the world.

Gorbachev, an idealistic (rather than cynical) Communist, well understood that the Soviet system had failed and was in deep need of radical transformation: glasnost (greater transparency), perestroika (reorganization of the economy), and democratization. His efforts toward all of these produced, at best, mixed results and, in the end, brought about the dissolution of the USSR.

Was transforming a USSR so corrupt and dogmatic, its political culture so toxic, merely a Herculean or inherently Sisyphean task? Was its dissolution inevitable (and a peaceful dissolution such as Gorbachev engineered the best outcome possible)? Or could someone better equipped than Gorbachev have produced the transformation and produced an ethical and humane Soviet Union?

Taubman concludes:

Gorbachev was a visionary who changed his country and the world—though neither as much as he wished. Few, if any, political leaders have not only a vision but also the will and ability to bring it fully to life. To fall short of that, as Gorbachev did, is not to fail. … The Soviet Union fell apart when Gorbachev weakened the state in an attempt to strengthen the individual. Putin strengthened the Russian state by curtailing individual freedoms. The burgeoning Russian middle class, estimated at 20 percent of the population, has Gorbachev to thank for opening the door to a better life—even if its members have been slow to recognize him as their benefactor. Too many Russians compensated for the sense of worthlessness brought on by the loss of empire with conspicuous consumption and glorification of the state. Will they or their children or their grandchildren still feel the same about Gorbachev fifty years from now?

Will we?

Gorbachev presents as a complex figure, one not easily assessed at this point in history. Taubman intimately portrays an epic tragic hero of Sophoclean proportion. Gorbachev is likely to be a subject of interest to future historians for centuries, perhaps millennia. His name and career may remain an object of fascination long after the names of the vast majority of world leaders have been forgotten.

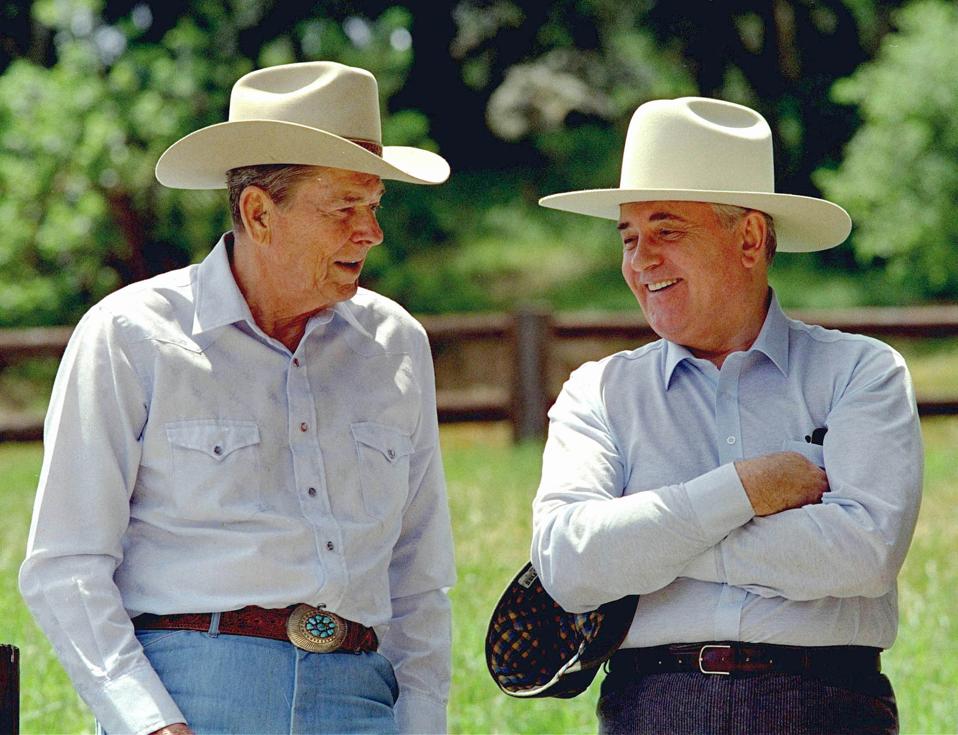

Mikhail Gorbachev, whose 87th birthday we celebrated this month, is perched on the precipice of eternity. Let’s do him, and ourselves, the courtesy of paying due attention to his life and statesmanship while he is still amongst us. Thank you, Prof. Taubman.