Before we salute “The Sting” as one of the most acclaimed and popular and enduring and exquisitely crafted blockbusters of all time, let’s get the Poker Quibbles and Beefs out of the way, shall we?

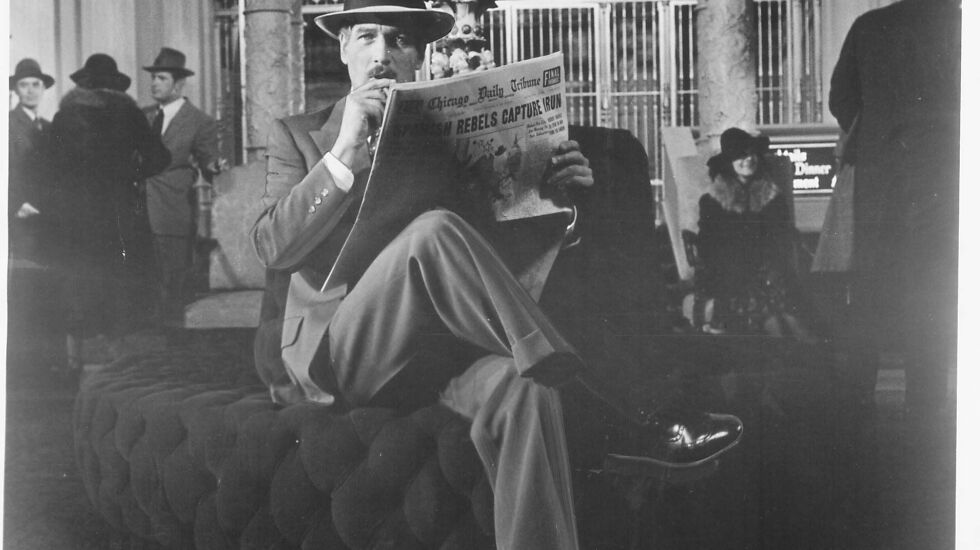

In a crisply edited scene set onboard the 20th Century Limited express train from New York City to the LaSalle Street Station in Chicago, the hotheaded and conniving mob boss Doyle Lonnegen (Robert Shaw) aims to swindle Paul Newman’s boisterous and seemingly drunk Chicago bookie “Shaw,” real name Henry Gondorff, in a high-stakes game of five-card draw. Along the way, various players at the table commit a number of moves that would never be allowed in such a game, from making “string bets,” i.e., “Call and raise,” to splashing the pot, to Lonnegen adding to his stack of chips in the middle of the hand.

Ah well, it still makes for a great payoff when Lonnegen displays his “winning” hand of four nines — only to see Shaw/Gondorff has four Jacks. The hustler, so to speak, was hustled, and there was nothing he could do about it. As he later screams at his henchman: “What was I supposed to do, call him for cheating better than me in front of the others!”

Great stuff — and just one of the many beautifully executed set pieces that helped catapult “The Sting” to 10 Oscar nominations and seven wins, including best picture, best director, best film editing and best original screenplay, and a box office gross of more than $160 million. To this day, “The Sting” is the 21st most successful film of all time, with an inflation-adjusted take of some $815 million.

Director George Roy Hill’s second film with Robert Redford and Paul Newman after “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” (1969) further solidified Redford’s superstar status and gave Newman a hit after a string of disappointments including “WUSA,” “Pocket Money” and “The Mackintosh Man.” As we approach the anniversary of “The Sting,” released 50 years ago this month, a few things to note if you’re planning a rewatch or you’re going to experience this still-great gem for the first time.

***

The extended prologue sequence (which carries a heavier and more somber tone than the story that follows) is set in Joliet, and the remainder of the film is set nearly entirely in Chicago, but most of the 1936 period-piece locations were shot at Universal Studios in Hollywood and in various spots in the greater Los Angeles area:

- Henry Gondorff’s Chicago carousel, which is actually a front for a brothel, is the Loof Hippodrome Carousel on the Santa Monica Pier. (In the film, the Chicago skyline appears in the background through the magic of matte artwork.)

- The FBI’s ad hoc headquarters is the old Koppel Plant storage facility in the San Pedro Harbor District.

- Even the downtown L is a set that was built on the Universal back lot for Norman Jewison’s largely forgotten 1969 comedy “Gaily Gaily,” which was based on Ben Hecht’s early years working as a newspaper reporter in Chicago and starred Beau Bridges as one “Ben Harvey.”

- The diner in “The Sting,” another backlot set, is the same diner where Marty McFly crosses paths with his father George in the first “Back to the Future.”

***

In David S. Ward’s original script, the character of Henry Gondorff was reportedly an older, slovenly, supporting character. That quickly changed after Paul Newman said he wanted to play Henry, who was elevated to handsome co-star status.

The veteran Western actor Richard Boone was slated to play Lonnegan, but inexplicably stopped returning the producers’ calls, so Robert Shaw was signed. Noted producer Michael Phillips in an article in the Guardian, “Luckily, Shaw turned out to be the most entertaining antagonist you could imagine … [and] Shaw’s limp was genuine. He had damaged his leg playing racquetball and couldn’t walk properly.”

***

For all its popularity, you don’t hear a lot of film buffs quoting “The Sting” like they do with “The Godfather.” We remember the action and the visual grace of the movie, particularly in the con scenes, than the dialogue. That doesn’t mean Ward’s screenplay isn’t loaded with terrific lines, including Lonnegen’s repeated use of, “You follow me?” as a way of saying, “You’ll do what I just said, or else.”

Then there’s the moment when Hooker sees Lonnegen for the first time at New York’s Grand Central Terminal (“played” by Chicago’s Union Station) and says, “He’s not as tough as he thinks,” and Gondorff retorts, “Neither are we.”

I also love the moment of genuine honesty between these two lifelong con men when Gondorff says, “You can’t play your friends like marks, Hooker,” as well as the scene when Hooker shows up at Loretta’s apartment door in the middle of the night and she says, “I don’t even know you,” and he replies, “You know me. I’m the same as you. It’s 2 in the morning and I don’t know nobody.”

So it goes with Johnny Hooker.

“The Sting” is brilliant and breezy entertainment, but there’s also something melancholy and self-destructive about that character, played so well by Redford in the role that earned him his one and only Oscar acting nomination. When Johnny takes down a mark for the biggest take of his life in Joliet, he blows three grand on one bet on a rigged roulette wheel. And after the major score from the “Wire” con, Johnny is set for life, but he doesn’t even stick around for his share of the take, telling Gondorff, “Nah. I’d only blow it.”

Henry took great joy in the art of the con. Johnny? It seemed more like something to do between sleepless nights.

.jpg?w=600)