Moral values are the principles that guide a person’s perceptions of good and bad, and right and wrong. They shape our prejudices, political ideologies and many other consequential attitudes and actions.

It’s tempting to assume that a person’s moral values are stable across time and circumstances, and to some extent they are — but not entirely. Moral values are malleable and can sometimes change depending on the specific thoughts, feelings and motivations that arise in different situations.

Our research examined whether moral values might change with the seasons, too.

Changing values

Seasons are characterized not just by changes in the weather, but also by many additional changes in our surroundings and the rhythms of our lives. These may include spring cleaning, spending more time with family in summer, back-to-school shopping in the autumn or preparing for winter holidays.

Consequently, changes in the seasons lead to changes in the things that people think, feel and do. Most people know that seasonal changes in the weather have effects on people’s moods, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Psychological research has revealed seasonal effects on attention and memory, generosity, colour preferences and many other things.

And so, in our recent research, we investigated whether there might also be seasonal cycles in the moral values that people endorse.

We examined five core principles that previous research has identified as fundamental moral values. Two of these principles — don’t hurt other people and treat all people fairly — pertain to individual rights and are referred to as “individualizing” values.

Three other principles — be loyal to one’s group, respect authority and maintain group traditions — promote group cohesion and are referred to as “binding” values.

Most people endorse all these values, but people differ in the extent to which they prioritize them, and these priorities have important implications. People who prioritize individualizing values are more politically liberal, whereas people who prioritize binding values are more conservative, more punitive and express stronger prejudices against out-groups.

Seasonal cycles

Do the seasons affect the extent to which people endorse these core moral values? To find out, we obtained data from YourMorals, a research website that uses online survey methods to assess people’s self-reported endorsement of all five of these core moral values.

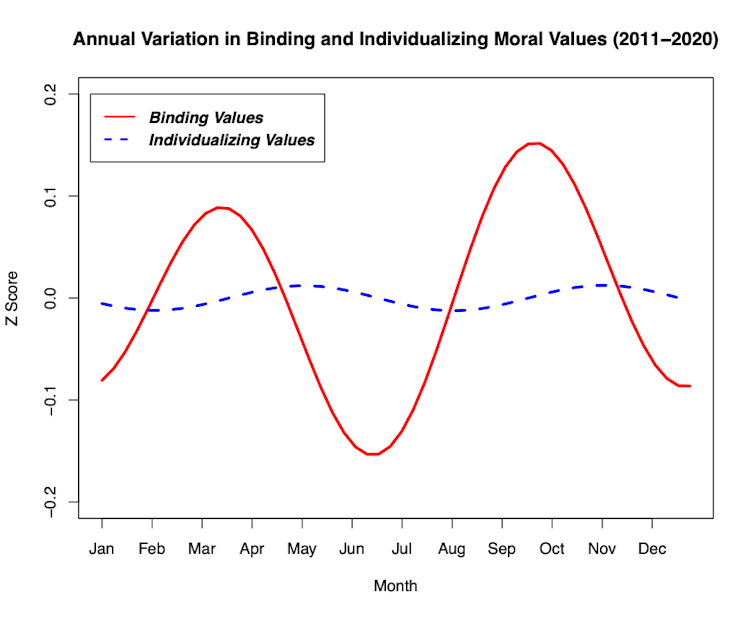

Our analyses focused on the values reported by 232,975 respondents in the United States across a decade (2011-20) of data. The results revealed no apparent seasonal cycle in Americans’ endorsement of individualizing values, but there was clear and consistent seasonal cycle in Americans’ endorsement of all three binding moral values.

This seasonal cycle was bimodal, with two peaks and two valleys each year: Americans endorsed binding moral values (valuing loyalty, authority and group traditions) most strongly in the spring and autumn, and least strongly in midsummer and midwinter. This bimodal seasonal cycle in binding moral values showed up again and again in the data, year after year.

This seasonal cycle in binding moral values wasn’t unique to the U.S. either. Additional analyses on data from Canada and Australia revealed similar patterns: Canadians and Australians also endorsed binding moral values most strongly in the spring and autumn, and least strongly in midsummer and midwinter.

Anxiety patterns

What might explain this seasonal cycle in people’s endorsement of binding moral values? One possibility is that it has something to do with the perception of threat, which encourages people to close ranks within a group. Previous research has linked this to increased endorsement of binding moral values.

To test this idea, we analyzed data on an emotion associated with threat perception: anxiety. Results revealed that Americans’ self-reported anxiety showed the same bimodal seasonal cycle, and so did 10 years of data on Americans’ Google searches for anxiety-related words. This seasonal cycle in anxiety helps to explain the seasonal cycle in binding values.

This explanation raises a new question: what might explain the seasonal cycle in anxiety? Although we can only speculate, our analyses on moral values revealed an intriguing clue. The summertime dip in Americans’ endorsement of binding moral values was bigger in places with more extreme seasonal changes in the temperature. There was no such effect on the size of the midwinter dip.

Perhaps something similar might be going on with anxiety: maybe that summertime decrease is the result of pleasant weather, whereas the midwinter decrease is more of a holiday effect.

Double-edged sword

Regardless of the cause, seasonal cycles in binding moral values could have consequences that affect people’s lives, for better or worse. Binding moral values promote cohesion, conformity and co-operation within groups, which can be beneficial, especially when coping with crises.

The implication is that groups might cope better with crises that emerge in the spring and autumn, compared to those that occur in the summer and winter.

But binding moral values also promote distrust of people who fail to adhere to group norms and traditions. The implication is that there may also be seasonal cycles in prejudices against immigrants, racial minorities, LGBTQ+ individuals and anybody else who is perceived to be different.

People who more strongly endorse binding moral values are also more punitive, so there could be seasonal effects on judicial decision-making in the millions of legal cases that occur every year.

And given the link between binding moral values and conservative attitudes, there are potential implications for politics. One intriguing possibility: the timing of political elections (whether they are scheduled for summer or autumn, for instance) might have some subtle effect on some votes — which, for an election that is especially tight, might even influence its outcome.

Mark Schaller receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Ian Hohm does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.