Only at Alexander McQueen could a subterranean raw-concrete venue, as chosen by Seán McGirr for his debut show, feel like a respectful homage to the heritage of a fashion house. McQueen stands for savagery and for sentimentality, and old-timers love to reminisce about nights spent shivering in derelict car parks being outraged by the designer’s bumsters in the 1990s. In the event, a day of driving rain had left McGirr’s disused Chinatown food market bleaker than he perhaps intended, chilled to its raw bones and perilous with puddles. Which might have been a coincidence, or might – a certain witchiness being a strand of the McQueen DNA – have been the spirit of Lee McQueen dialling in from the afterlife with his distinctive dark sense of humour.

The models scowled, arms wrapped tight around their bodies, hurrying along the catwalk as if they were navigating a particularly sketchy street on the late-night walk home from a club. The first wore a dress in laminated black jersey, glossy and salty-sweet as liquorice, wrapped clingfilm-tight. It was a nod to a dress made of pallet tape from Lee McQueen’s collection The Birds, shown in a warehouse in London’s then-gritty King’s Cross in 1995. It was also a great dress. The McQueen language was strong in the silhouette. Shoulders were padded until the models hunched in statuesque coats; trousers were shrunken and bum-hugging.

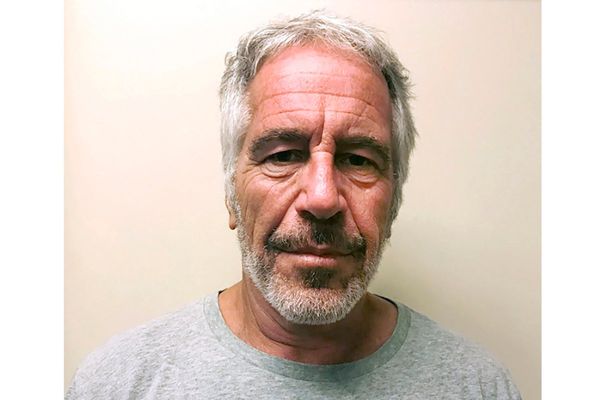

When the 35-year-old McGirr, blue-eyed and handsome with diamond hoops in each ear, was asked backstage whether he was intimidated to follow the much-loved Sarah Burton, and Lee McQueen himself, he kept his poise. “I don’t see it like that. I was just pumped to get going.” He said he wanted his McQueen to be about “people that I’d be curious to meet on the streets. The rough glamour of the East End, that kind of tattered opulence.” The outsider vibe extended to a celebrity-free front row. “When I look at pictures of McQueen’s shows in the 1990s, the girls look like people on the fringes. I’m into that idea of anti-politeness,” he said. Paparazzi photos of a young Kate Moss and Amy Winehouse were pinned on his moodboard, alongside archival McQueen images.

McGirr said he wanted the emotional tone to be “uplifting and upbeat”. Perhaps he forgot to tell this to the scowling models. Anyhow, he seemed to have early McQueen in his sights, the days when it felt like street and club wear. McGirr’s vision does not, as yet, have either the intense braininess or the master tailoring of the original McQueen, but this first showing felt aimed at conjuring the sharp-edged spikiness of that era, rather than the delicate, British folkloric, Princess of Wales-facing version of the house that evolved under Burton.

The roughly stitched wall hangings either side of the catwalk were more student digs than Paris salon. A safety pin moulded like a fish skeleton sketched by the famed Gonzo-illustrator Ralph Steadman for the invitation appeared as a silver brooch on lapels of coat jackets on the catwalk. Skulls were carved into earrings. There was energy and charm in party dresses embroidered with dazzling laser-cut crystal fragments – McGirr got the idea for the effect from a smashed phone screen – and in how he weaved in his own backstory with moulded-steel “car dresses” in colours he called Lamborghini yellow and Aston Martin blue. “My dad is a mechanic and I grew up talking about cars with him,” he said, adding that his parents were at the show, and that he planned to celebrate with “a hug from my mum, and maybe a bath”.

Having found himself the unwitting centre of a row about the absence of women in creative director roles, McGirr sensibly hung back from embracing McQueen’s more fetishistic extremes. The dubious syphilitic glamour of Lee McQueen’s bone-crunching corsets might have felt too provocative to those sensibilities. Leather lacing that Lee bound around women’s thighs in The Birds was confined to the calves of skinny jeans, and McGirr instead found exaggerated silhouettes in giant, chubby knitwear.