The career of Scott Walker, who has died aged 76, divided into three distinct phases. A restless quest for new soundscapes led him from the easy listening of the Walker Brothers’ wall-of-sound pop to the difficult listening of his avant-garde solo work via an interim reinvention as a lavishly orchestrated crooner and storytelling lyricist.

Walker, born Noel Engel in Hamilton, Ohio, to a Canadian mother and American father who was a manager in the oil industry, possessed a deep baritone to which critics variously ascribed the adjectives rich, brown, mahogany, velvet, noble, elegant, soaring and even fruity. His voice was unmistakable, yet he said in a recent interview: “I don’t like singers very much. There’s very few I really like. More and more, I listen to instrumental music.”

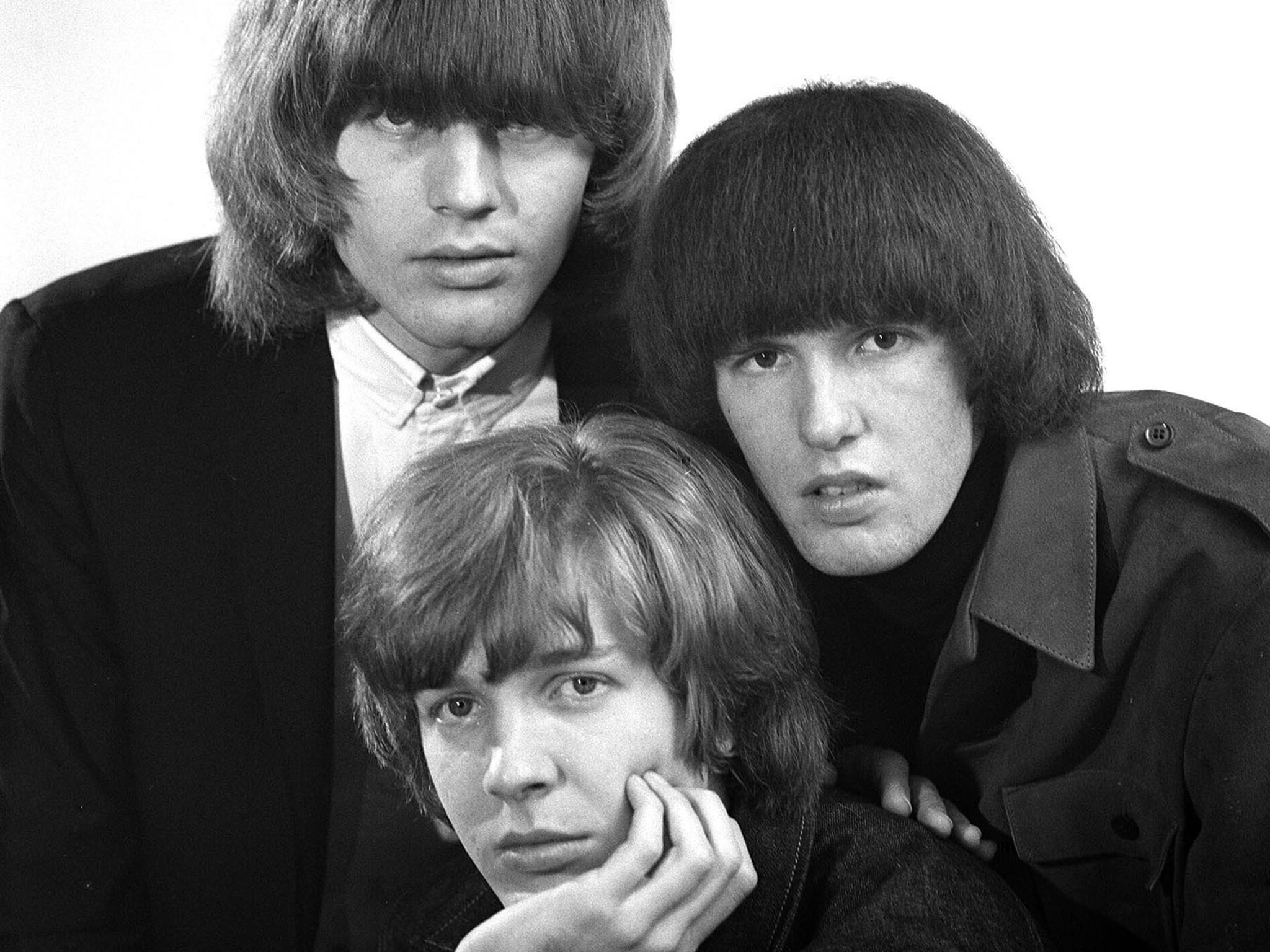

The majesty of his vocal style, which later won him admirers such as Jarvis Cocker of Pulp, Radiohead’s Thom Yorke and David Bowie (who called him “my idol since I was a kid”), was not initially apparent to record companies and colleagues. When the Walker Brothers formed in 1964, John Maus was the lead singer. Engel – or Scott Walker as he became, replacing Noel with his second name and joining Maus and drummer Gary Leeds in adopting the surname Walker – provided harmonies and bass guitar.

That changed in 1965. The trio, all Americans who had based themselves in the UK, released their second single, “Love Her”, with Scott out in front. Their reworking of what was originally an Everly Brothers B-side reached No 20 in the UK. When he sang it on ITV’s Ready! Steady! Go! his ascendancy within the group cemented. He also became an overnight sensation.

Their next three singles, all cover versions of teen-heartbreak songs, had a blue-eyed soul feel and Phil Spector-style production. “Make It Easy On Yourself” and “The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” reached No 1, while “My Ship Is Coming In” made No 3 (although none made the US top 10). Scott took the lead on each, and in 1967 the Walkers drew audience screams on a now-legendary tour with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Cat Stevens and Engelbert Humperdinck.

Scott, however, was weary of his pop-idol status, life on the road and the search for the next hit, being more interested in jazz, poetry, cinema and literature. In 1966 he briefly entered Quarr monastery on the Isle of Wight to study Gregorian chant. The following year he broke up the group and embarked on a solo career.

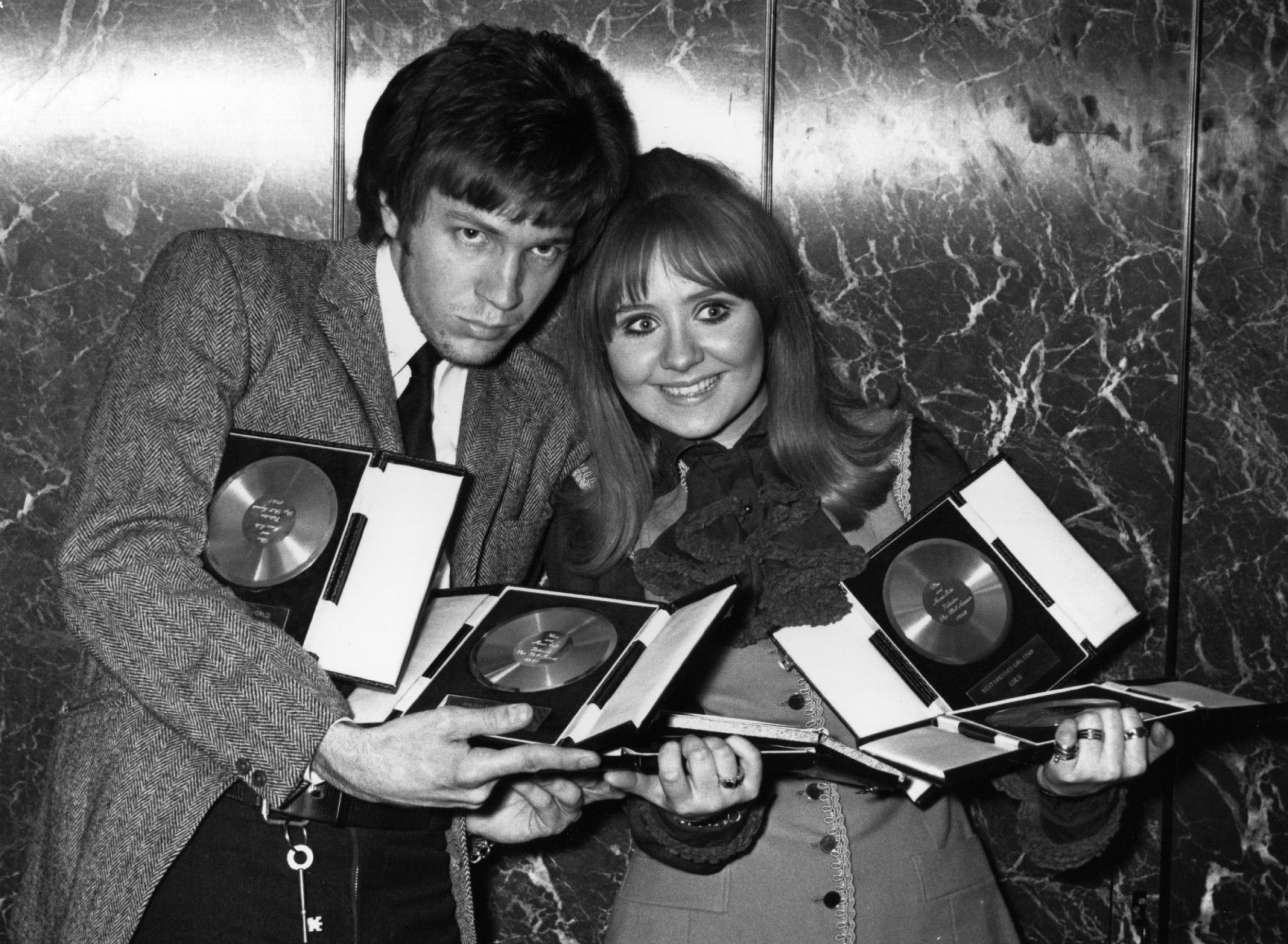

Over the next seven years he released 10 albums, with the first three, Scott, Scott 2 and Scott 3, reaching No 1, 3 and 1 respectively. The covers included several songs by Jacques Brel. Walker’s own contributions, swathed in symphonic sound and chronicling quirky characters living on the margins of society, were influenced by Brel, whom he hailed as “the most significant singer-songwriter in the world”.

A 1969 BBC TV series, Scott, led to a compilation album of studio renditions of material from the show, Scott Walker Sings Songs From His TV Series, which peaked at No 7. It included the standards “The Look Of Love” and “The Impossible Dream”, but Walker was again growing uncomfortable with middle-of-the-road conventionality. His next LP, Scott 4, was darker and more experimental. It became the first of six consecutive Walker albums which failed to chart.

He later called the 1970s – which began with his becoming a British citizen – “my wilderness years”. He became reclusive and drank heavily. Few devotees complained, though, when the Walker Brothers reformed in 1975. The reunion delivered one hit, Tom Rush’s “No Regrets”, and three albums. Before they parted again there was a pointer to a new direction on 1978’s Night Flights in the form of the unsettling, discordant track “The Electrician”.

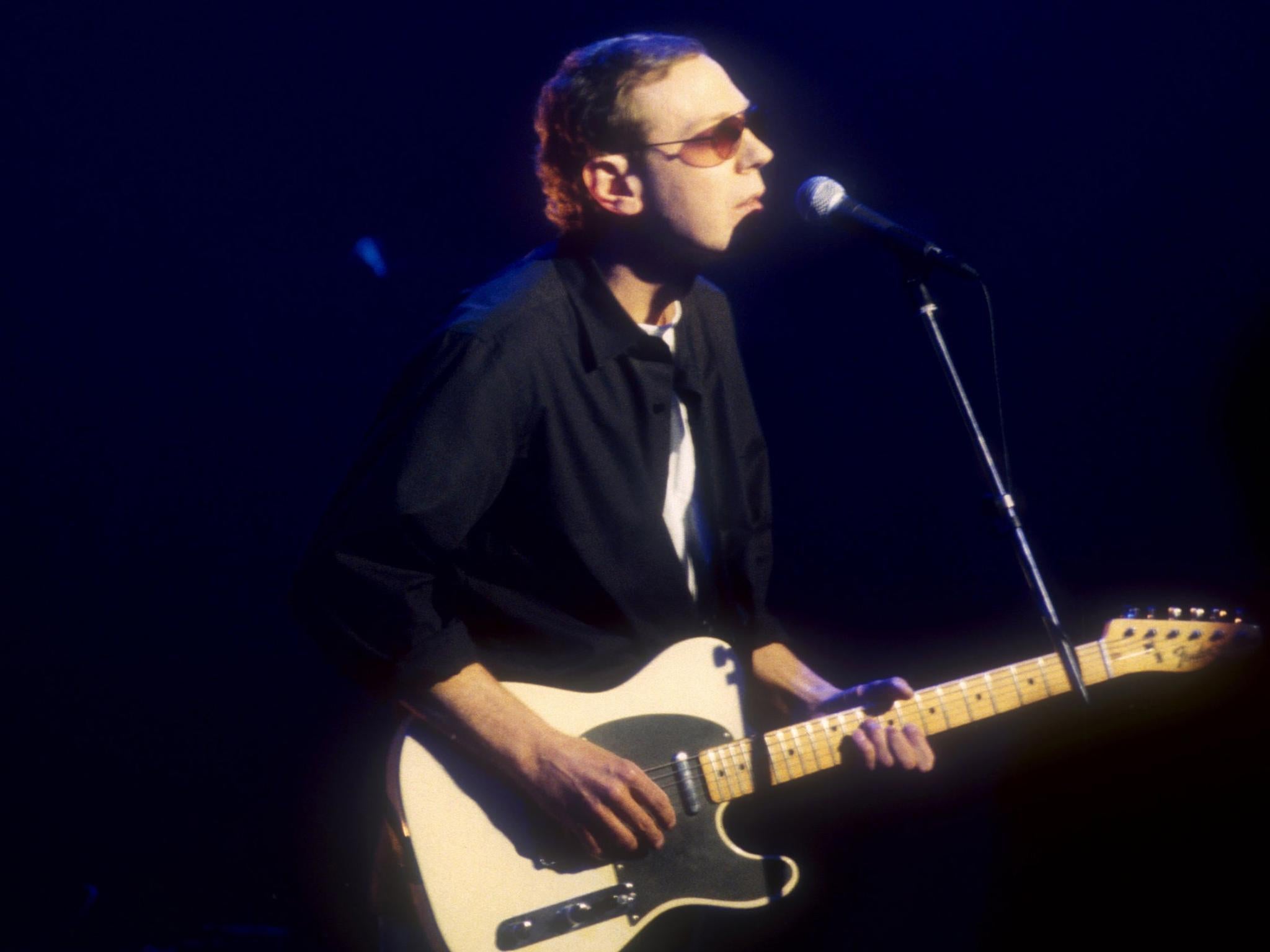

A 1981 collection of Walker solo songs, curated by mega-fan Julian Cope of The Teardrop Explodes and reverentially titled Fire Escape In the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker, arguably earned him a deal with Virgin Records. The liaison produced 1984’s Climate of Hunter, which prompted high praise and low sales. The dichotomy persisted with Tilt (1995), The Drift (2006) and Bish Bosch (2012) confirming the 21st-century Walker as enigmatic and uncompromising, eschewing melody in favour of discordant “blocks of sound”.

Among those Walker worked with as producer were Pulp and Bat for Lashes. In 2000 he curated the Meltdown summer music festival at London’s South Bank – but did not sing, having long disliked performing live – while in 2017 the Royal Albert Hall staged a Proms concert of his songs.

He interpreted Bob Dylan’s “I Threw It All Away” for the soundtrack of To Have and To Hold and recorded a song for the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough, only for it be dropped for being too sombre. Last year he created the score for Brady Corbet’s film Vox Lux.

A 2006 documentary named after a Walker song, 30 Century Man (which Bowie executive-produced) showed him overseeing the punching of a side of raw pork as percussion for the bleak, disturbing “Clara” on The Drift. Yet in one of his final interviews he said: “I feel I’m writing for everyone. They just haven’t discovered it yet. I’ll be six feet under, but they will.”

He is survived by his partner Beverly and daughter Lee.

Scott Walker (Noel Scott Engel), singer, songwriter and producer, born 9 January 1943, died 22 March 2019