Scientists have developed a tool they say is able to briefly restore circulation and some brain activity — but not consciousness or global electric functions — in the brains of pigs 4 hours after death.

Why it matters: Researchers hope to eventually have the ability to restore some lost brain functions in humans after injuries or cell death from stroke or diseases. This study, published in Nature Wednesday, offers a new tool likely to enable progress toward that goal. However, it's also expected to pose ethical dilemmas down the road — such as, will we eventually have to redefine the line between life and death?

Background: The standard definition of brain death has remained relatively unchanged for a little more than 50 years.

- Human brains (and that of all mammals) are very sensitive to decreased oxygen levels, and interruptions to blood flow are believed to cause irreparable brain damage.

- But, recent research has shown certain structures of the brain may remain viable for hours after death, like mitochondria.

- In a press briefing discussing this study's findings, co-author Nenad Sestan of Yale School of Medicine said: "We questioned the belief that widespread cell death is unavoidable minutes or even hours after death."

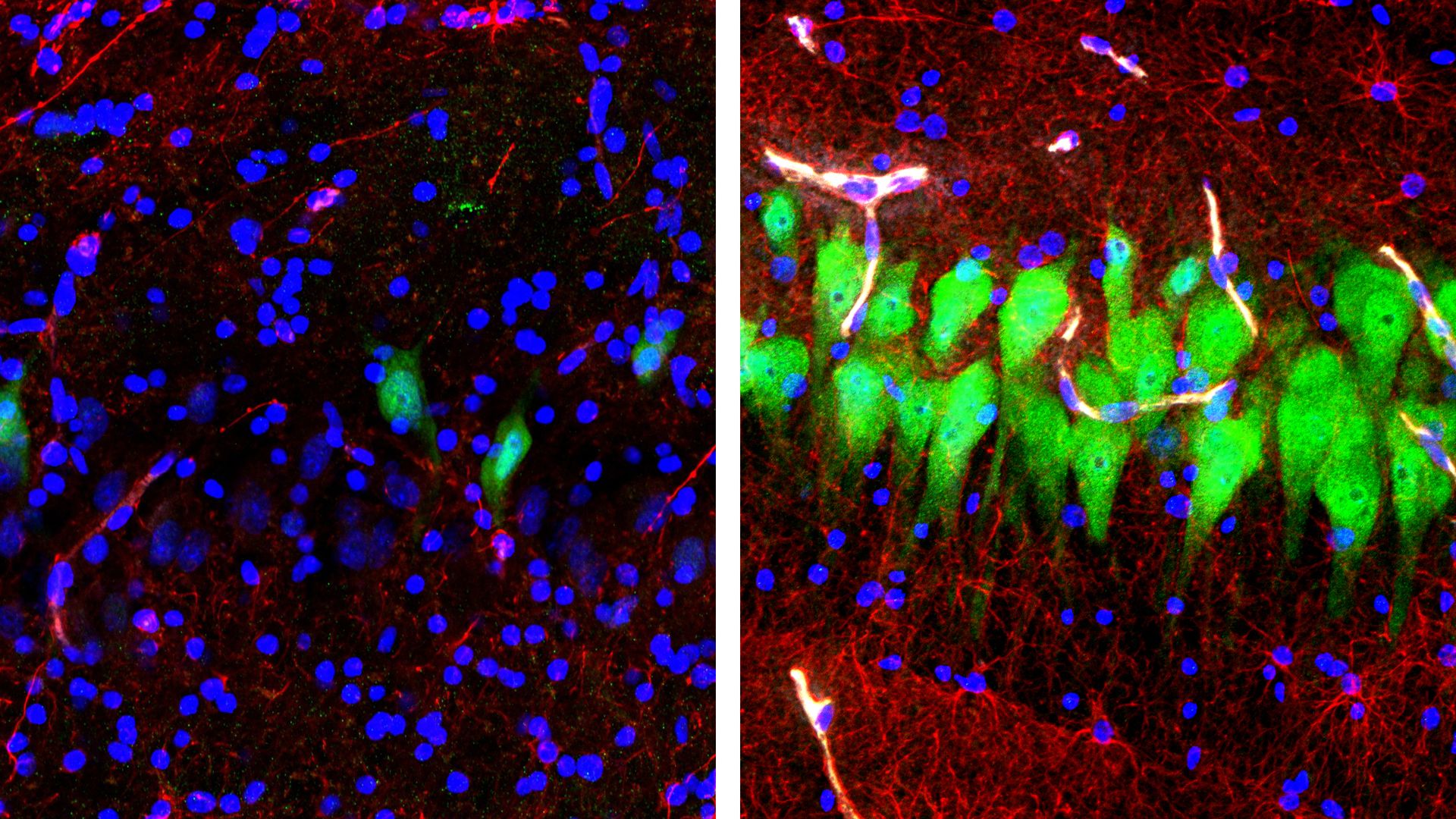

What they did: The team developed a tool called BrainEx and then tested it on the whole brains of 32 pigs, which had been slaughtered at a pork plant 4 hours earlier. They compared this with whole brains from pigs slaughtered at the same time but left untreated.

- Pig brains are similar in some aspects, including size, to that of humans.

- They drained the blood and pumped a cell-free solution called BEx perfusate, which had protective, stabilizing and contrast agents, into the brain's main arteries at normal body temperature.

- One of the key ingredients was a blocker called lamotrigine, which limits neuronal activity, to help preserve the brain cells.

What they found: The researchers say they found some of the brain cells were surprisingly resilient for those in BrainEx compared to those untreated.

- "We found that tissue and cellular structure is preserved and cell death is reduced. In addition, some molecular and cellular functions were restored," Sestan said.

- The platform restored brain circulation and some cellular functions — but there was no evidence for global electrical brain activity associated with awareness, perception or other higher-order brain functions, they said.

- They did see some new electrochemical responses after they took a sample of tissue and washed out the perfusate solution — which raises questions about whether there'd be more brain activity seen without the blocker in the solution — but they did not pursue this discovery in this trial, the researchers said.

What they're saying: "This story is really not about making dead people live again," but creating a new research model to examine how the whole brain works via pigs, says Jonathan Moreno, a bioethicist from the University of Pennsylvania who was not part of this study.

- Andrea Beckel-Mitchener, the team lead for the BRAIN Initiative at the NIH’s National Institute of Mental Health which co-funded the research, tells Axios they are "aiming for revolutionary new approaches to studying the brain."

- "The real advantage here is that this has never been done before in a large, intact mammalian brain," Beckel-Mitchener says. The results show "the brain cells are resilient and under the right conditions they can maintain [some] healthy functions many hours after the loss of blood flow."

What's next: This experiment was designed to create the tool, and the scientists were very careful to maintain ethical guidelines, Moreno tells Axios. But, what happens later could require conversations and new guidelines, he adds.

- "To me the elephant in the room, or the pig in the room shall we say, is consciousness," the scientific definition of which remains under scientific debate, Moreno says.

- A group of scientists wrote a similar view in their commentary published in Nature, calling for the development of guidelines on preservation or restoration of whole brains, including "how should researchers try to detect signs of consciousness or sentience?"

- They add that the study “throws into question long-standing assumptions about what makes an animal ― or a human ― alive.”

- In a separate commentary in Nature, scientists point to the problem of how this could affect human transplants, since if people have hope of resuscitating the brain, there could be fewer organ transplants, and roughly 20 Americans die every day waiting for a transplant now.

- Beckel-Mitchener says the Brain Initiative has an ethics council that deliberates on these new technologies, as they believe "science [should] evolve in parallel with the ethics conversation."

The authors state clearly in the paper that as experiments using BrainEx gravitate towards human brain research:

The bottom line: This new tool offers the possibility for major advances in neuroscience — but will also require grappling with thorny questions.