In 1984, when a farmer was brought into the emergency room of San Vicente de Paul University Hospital in Medellín, Colombia, with complaints of mood changes and memory loss, it became very clear to Francisco Lopera, a neurology student at the time, that the man had Alzheimer’s disease, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder that’s the most common cause of dementia. But for Lopera, something wasn’t adding up.

“The one thing that didn’t make sense to me was that he was very young — the patient was 47 years old. Alzheimer’s usually begins after age 65,” he told NPR’s Radio Ambulante in 2021.

Lopera eventually discovered the man and many others in a large extended Colombian family carried a mutation on a gene called presenilin-1. Carriers of this E280A variant developed early-onset Alzheimer’s disease — a condition characterized by mild cognitive impairment starting in a person’s early 40s, with them reaching full-blown dementia by age 49, and death in their 60s.

Over the last several years, members carrying the Paisa mutation, as it was later dubbed, have become a prominent research cohort for early Alzheimer's. In 2019, scientists made a surprising discovery: One female clan member dodged the disease altogether, remaining unimpaired until her 70s. Now another individual appears to have shared her fate, avoiding the worst of his family’s cruel neurodegeneration curse thanks to a rare, protective genetic variant, according to a study published Monday in the journal Nature Medicine.

“What we have done with the study of these two protected cases is to read mother nature,” Lopera, the study’s first author, and director of the Antioquia Neuroscience Group at the University of Antioquia in Medellin, said in a press release.

“A great door has been opened for the prevention and treatment of incurable diseases.”

Two different protective genes

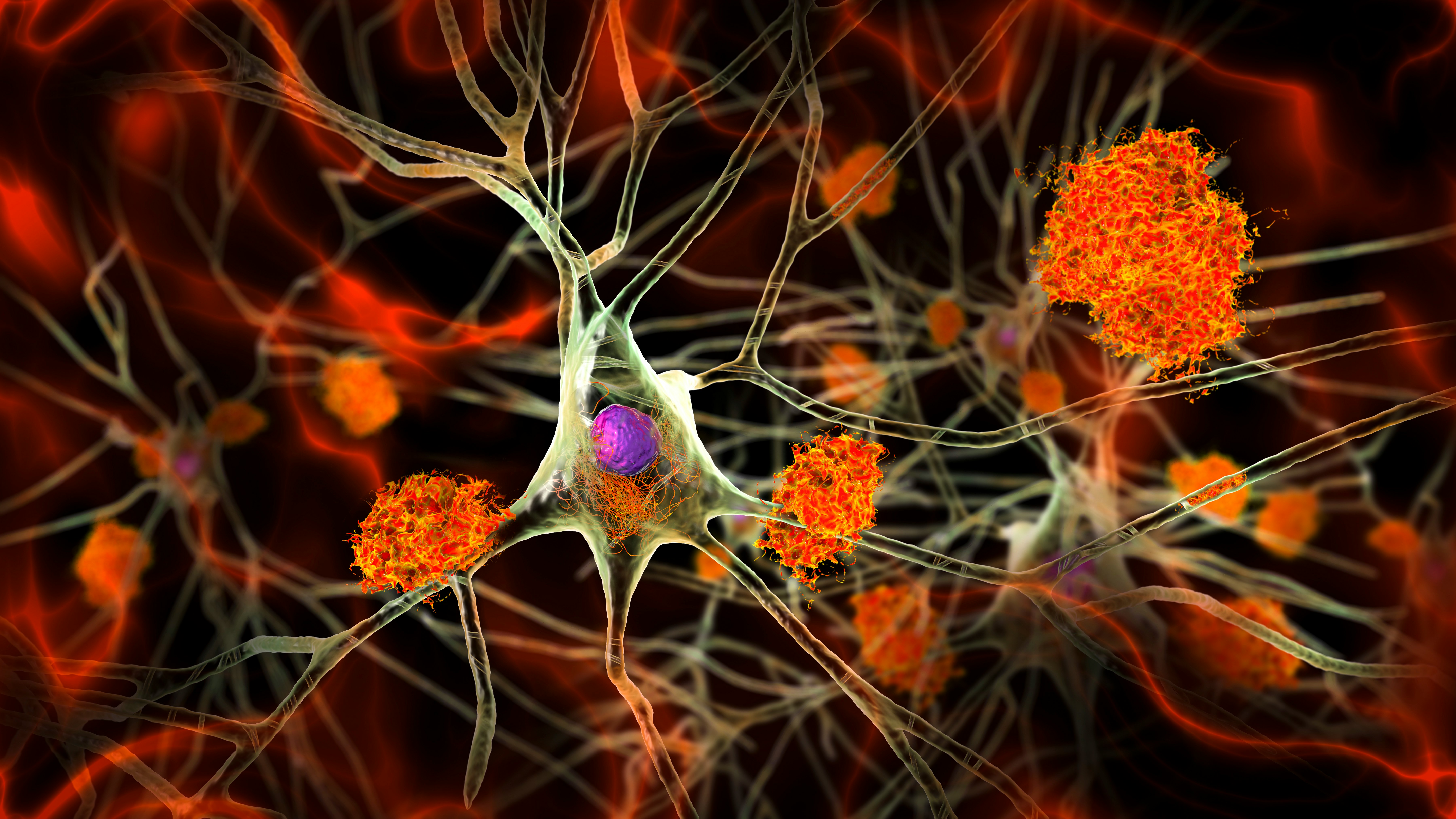

While the woman from 2019 carried the Paisa mutation and developed plaques in her brain made of sticky proteins called amyloids, her memory deficits were minor, and her cognitive faculties remained pretty normal and unchanged.

Researchers were stumped until they discovered the woman also carried an extremely rare genetic variant affecting a different Alzheimer’s-related gene called APOE. This gene codes for a protein, apoE, that helps ferry cholesterol and other types of fat in the blood. There are three common variants of the APOE gene that either increase or decrease one’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s. (The underlying disease-causing mechanism behind these variants is still an area of research.) For this woman, she appeared to carry the Christchurch mutation in both copies of her APOE gene, which shielded her from the neurodegenerative effects of Alzheimer’s disease.

The other individual carrying the Paisa mutation, who remained cognitively intact until his late 60s before developing mild dementia in his early 70s and dying at 74, did not have Christchurch genetic variant. He instead harbored a mutation in the RELN gene that makes a protein called reelin involved in regulating neuronal migration and is also implicated in neurological conditions like schizophrenia and autism.

While there have been a few studies looking at the RELN gene in Alzheimer’s, much is still unknown. To suss that out, the researchers genetically engineered mice with the same mutation the man had and found it altered brain proteins called tau, preventing them from tangling, which is what happens in Alzheimer’s disease alongside amyloid plaque formation.

This individual had a lot of amyloid plaque build-up just like the 2019 patient, as well as some tau tangles, despite the protective mutation. The one place in the brain that was relatively unscathed for both was the entorhinal cortex, a region of the brain serving as a major hub connecting the neocortex (outer layer of the brain) with the hippocampus involved in memory formation and spatial navigation.

“This case indicates that the entorhinal region may represent a tiny target that’s critical for protection against dementia,” Yakeel Quiroz, the paper’s co-author, and director of the Familial Dementia Neuroimaging Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, said in the same press release.

More research on the horizon

The researchers believe these genetic variants are protecting the two individuals from developing those proteins like tau from going haywire. This mode of action points to a greater role for tau proteins in Alzheimer’s disease development and progression than the current theory that centers neurodegeneration around amyloid plaque formation and build-up.

Many immunotherapy drugs approved for treatment by the FDA, such as lecanemab, or undergoing clinical trials like Eli Lilly’s donanemab focus on eradicating these plaques. But the results of these two case studies suggest more scientific effort needs to be channeled toward tau proteins or targeting key brain structures like the entorhinal cortex.

More investigations into these protective gene variants will be needed before we can devise any adequate Alzheimer’s disease treatments. Lepora and his colleagues are hopeful their research is making the necessary gains toward that goal, especially as the burden of Alzheimer’s disease patients is growing fast — in 2023, an estimated 6.7 million Americans age 65 years are or will be living with the disease.

“The genetic variant we have identified points to a pathway that can produce extreme resilience and protection against Alzheimer’s disease symptoms,” Joseph Arboleda-Velasquez, the study’s co-author and an associate scientist at Mass Eye and Ear. “These are the kinds of insights we cannot gain without patients. They are showing us what’s important when it comes to protection and challenging many of the field’s assumptions about Alzheimer’s disease and its progression.”