NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has made the most precise and direct measurements of the total amount of light produced by our universe.

The question of just how dark the universe is has vexed astronomers for decades, because from our stretch of the solar system, scattered sunlight and interplanetary dust and ice interfere with the measurement of the ambient light produced by the cosmos' hundreds of billions of galaxies.

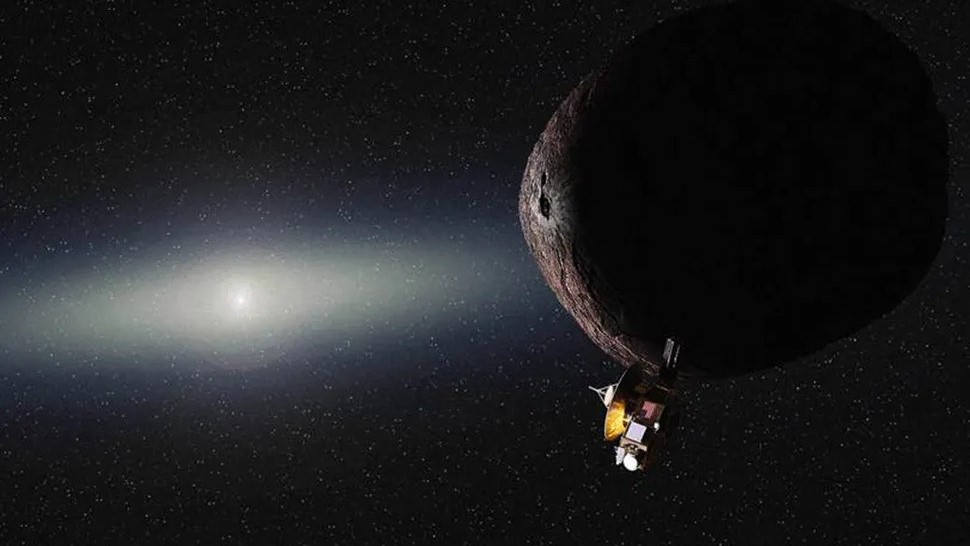

Now, more than 18 years after its launch and nine years after mapping the surface of Pluto, the New Horizons spacecraft has produced an answer. Drifting more than 5.4 billion miles (8.8 billion kilometers) from Earth in the cold, dark space of the outer solar system, the spacecraft measured the universe's light. The researchers published their findings Wednesday (Aug. 28) in the The Astrophysical Journal.

The background of visible light added up over the universe's lifespan (called the cosmic optical background or COB) is important to astronomers because it helps them to match the light coming from stars and the exteriors of black holes with that predicted by theory.

Related: Supercharged 'cocoon of energy' may power the brightest supernovas in the universe

If these two figures line up, then our current picture of the universe is mostly correct; but if they misalign, it could mean that there's more going on in the universe than we presently know. Yet accurately measuring the COB from Earth, or even the inner solar system, is extremely difficult.

"People have tried over and over to measure it directly, but in our part of the solar system, there's just too much sunlight and reflected interplanetary dust that scatters the light around into a hazy fog that obscures the faint light from the distant universe," co-author Tod Lauer, a New Horizons co-investigator and an astronomer at the National Science Foundation NOIRLab in Tucson, Arizona, said in the statement. "All attempts to measure the strength of the COB from the inner solar system suffer from large uncertainties."

To overcome this problem, the New Horizons spacecraft waited until it was far away in the Kuiper Belt, on its way to interstellar space. Then, it used its body to shield the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) from the sun's light and pointed itself away from the Milky Way's bright core. The spacecraft then snapped two-dozen snapshots of the universe.

After carefully calibrating the light levels observed with those taken in infrared by the Planck satellite to screen out dust, the researchers arrived at their estimate for the universe's visible light — a radiant intensity 11.16 nanowatts per steradian.

The result was consistent with the light intensity thought to be generated by all galaxies over the past 12.6 billion years, meaning that (at least in the visible spectrum) astronomers are unlikely to be missing anything big in their models.

"The simplest interpretation is that the COB is completely due to galaxies," Lauer said. "Looking outside the galaxies, we find darkness there and nothing more."