Archaeologists have found preserved human brains dating back thousands of years ago, but little was known about the preservation of the organ. Until now. The discovery of over 4,400 human brains spanning 12,000 years may have helped find a new preservation mechanism, presenting an untapped resource for bioarchaeological studies of human evolution and health.

The brain is thought to be among the first human organs to decompose after death, the University of Oxford Forensic Anthropologist Alexandra Morton-Hayward wrote with her co-authors.

This is why the discovery of brains preserved in the archaeological record is regarded as unusual, the researchers stated in a new paper published on Wednesday (March 20) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Although mechanisms such as dehydration, freezing, saponification, and tanning are known to allow for the preservation of the brain when they are less than 4,000 years old, the discovery of older brains is much rarer.

Archaeologists uncovered over 4,400 preserved human brains spanning 12,000 years, potentially revealing a new preservation method

Nevertheless, after collecting more than 4,400 human brains across approximately 12,000 years, researchers found that brains preserved in the absence of other soft tissues indicate an unknown mechanism that may be responsible for preservation, particularly to the central nervous system.

“Some soft tissue preservation is well-studied. Dehydrating and freezing—think of Egyptian mummies or frozen bodies,” Alexandra told Science.

She continued: “Sometimes fat in the body can turn to a soaplike substance after death that preserves tissue, a process called saponification.

“And in peat bogs, the acid in sphagnum moss puts soft tissue through a tanning process that often preserves brain tissue.

“But in this paper, we’ve identified a fifth category: hundreds of brains that are preserved even when all the body’s other soft tissue has decomposed.”

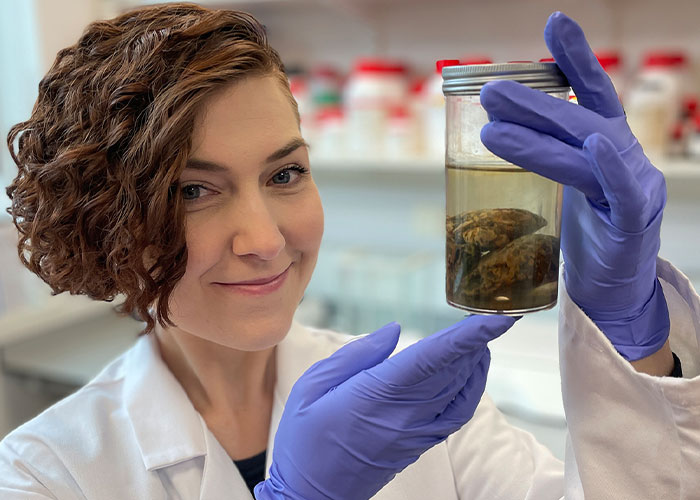

Forensic Anthropologist Alexandra Morton-Hayward co-wrote the study

The scientists involved in the study identified a total of 4,405 preserved human brains from 213 unique sources, which were reported from every world region except Antarctica. Moreover, the brains were universally described as discolored and shrunken.

The researchers compared the number of preserved human brains with other soft tissues in archaeological databases, and they found that while internal soft tissues like muscle and gut were rare, preserved brains were much more common.

The result suggested that brains have been preserved more frequently than previously thought.

“My belief, based on the evidence, is that it’s something particular to the central nervous system, because of the brain’s unique biochemistry,” Alexandra told Science.

She further explained: “There are fats in the brain that aren’t expressed anywhere else in the body, and sulfur-containing proteins that are part of the brain’s signaling mechanism.

“I think all that is fusing together to form a recalcitrant material that can preserve for a really long time.”

The brains that were discovered were described as discolored and shrunken

Ancient brains may provide new and unique palaeobiological insights, helping us to better understand the history of major neurological disorders, ancient cognition and behavior, and the evolution of nervous tissues and their functions, the scientists stated in the paper.

As for the ethical concerns of working with a long-deceased person’s brain, Alexandra explained that in the U.K., research into human soft tissues was regulated by a law known as the Human Tissue Act (HTA).

Subsequently, if the tissues are more than 100 years old, the material isn’t deemed to fall under the HTA’s purview.

The anthropologist added: “But obviously, regardless of how old they are, we still want to treat these remains with respect and with dignity.

“After years of working as an undertaker, I’m always conscious these are human beings.”

The discovery sparked different reactions on social media