Teri Patrick bristles at the idea she wants to ban books about LGBTQ issues in Iowa schools, arguing her only goal is ridding schools of sexually explicit material.

Sara Hayden Parris says that whatever you want to call it, it's wrong for some parents to think a book shouldn't be readily available to any child if it isn’t right for their own child.

The viewpoints of the two mothers from suburban Des Moines underscore a divide over LGBTQ content in books as Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds pushes an especially sweeping crackdown on content in Iowa school libraries. The bill she's backing could result in the removal of books from school libraries in all of the state's 327 districts if they're successfully challenged in any one of them.

School boards and legislatures nationwide also are facing questions about books and considering making it easier to limit access.

“We’re seeing these challenges arise in almost every state of the union,” said Deborah Caldwell-Stone, director of the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. “It’s a national phenomenon.”

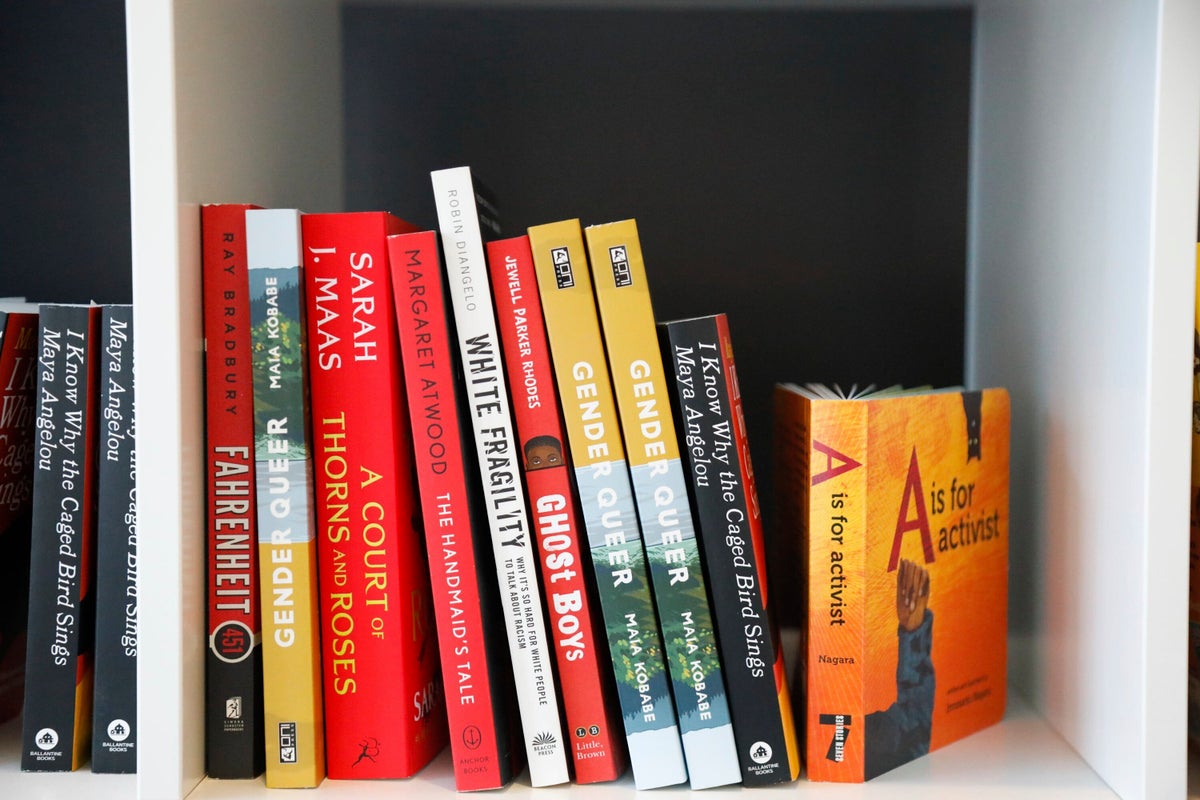

Longstanding disagreements about content in school libraries often focus this year on books with LGBTQ themes as policymakers nationwide also consider limiting or banning gender-affirming care and drag shows, allowing the deadnaming of transgender students or adults in the workplace, and other measures targeting LGBTQ people.

The trend troubles Kris Maul, a transgender man who is raising a 12-year-old with his lesbian partner in the Des Moines area and wants school library books to reflect all kinds of families and children. Maul argued that those seeking to remove books take passages out of context and unfairly focus on books about LGBTQ or racial justice issues.

LGBTQ people are more visible than even five years ago, Maul said, and he believes that has led to a backlash from some who hope limiting discussion will return American society to an era that didn’t acknowledge people with different sexualities.

“People are scared because they don’t think LGBTQ people should exist,” Maul said. “They don’t want their own children to be LGBTQ, and they feel if they can limit access to these books and materials, then their children won’t be that way, which is simply not true and is heartbreaking and disgusting.”

In Louisiana, activists fear a push by Republican Attorney General Jeff Landry to investigate sexually explicit materials in public libraries — and recently proposed legislation that could restrict children and teens’ access to those books — is being used to target and censor LGBTQ content.

Landry, who is running for governor, launched a statewide tip line in November to field complaints about librarians, teachers, and school and library personnel. Landry released a report in February that listed nine books his office considers “sexually explicit” or inappropriate for children. Seven have LGBTQ storylines.

In Florida, some schools have covered or removed books under a new law that requires an evaluation of reading materials and for districts to publish a searchable list of books where individuals can then challenge specific titles.

The reviews have drawn widespread attention, with images of empty bookshelves ricocheting across social media, and are often accompanied by criticism of Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican expected to run for president.

The state’s training materials direct the reviews to target sexually explicit materials but also say that schools should “err on the side of caution” when selecting reading materials and that principals are responsible for compliance.

DeSantis said the state has not instructed schools to empty libraries or cover books. He said 175 books have been removed from 23 school districts, with 87% of the books identified as pornographic, violent or inappropriate for their grade level.

The Iowa legislation comes amid efforts there to keep a closer eye on public school curriculums and make taxpayer money available to parents for private school tuition. Reynolds, the governor, has made such proposals the core of her legislative agenda, telling a conservative parents group that their work was essential to guarding against “indoctrination” by public school educators.

Under a bill backed by Reynolds, the titles and authors of all books available to students in classrooms and libraries would be posted online, and officials would need to specify how parents could request a book's removal and how decisions to retain books could be appealed. When any district removes a book, the state Education Department would add it to a “removal list,” and all of Iowa’s 326 other districts would have to deny access to the book unless parents gave approval.

At a hearing on Reynolds’ bill, Republican lawmakers, who hold huge majorities in both legislative chambers, said they might change the proposal but were committed to seeing it approved. The bill has passed a Senate committee and is awaiting a floor vote.

“The parents are the governing authority in how their child is educated, period,” said Sen. Amy Sinclair. “Parents are responsible for their child’s upbringing, period.”

Patrick, a mother of two, expressed befuddlement about why anyone would want to make sexually explicit books available to children.

“I have to believe that there are books that cater to the LGBTQ community that don’t have to have such graphic sexual content in them,” said Patrick, a member of a local chapter of Moms for Liberty, a conservative group that has gained national influence for its efforts to influence school curriculum and classroom learning. “There are very few books that have ever been banned and what we’re saying is, in a public school setting, with taxpayer-funding money, should these books really be available to kids?”

Hayden Parris, a mom of two from a suburb only a few miles away, understands the argument but thinks it misses the point.

“A kindergartner is not wandering into the young adults section and picking out a book that is called like, “This Book is Gay,” said Hayden Parris, who is leading a parents group opposed to Iowa's proposed law. “They’re not picking those books, and the fact that they can pick one out of several thousand books is not a reason to keep it away from everyone.”

Sam Helmick, president of the Iowa Library Association, said communities should decide what's in their libraries and that it's important for children to have access to books that address their lives and questions. Helmick didn't have that ability as a child, and students shouldn't return to that time, she said.

“Can we acknowledge that this will have a chilling effect?” Helmick asked. “And when you tell me that books about myself as an asexual, nonbinary person who didn’t have those books in libraries when I was a kid to pick up and flip through, but now publishing has caught up with me and I can see representation of me — those will be behind the desk and that’s not supposed to make me feel less welcome, less seen and less represented in my library?”