British Columbia is in the midst of an enduring drug overdose crisis that continues to claim hundreds of people every year with no end in sight. With a significant rise in deaths over the last seven years, innovative responses are urgently needed.

Among these responses is community drug checking, which continues to gain traction in both public health practice and research. Drug checking is a harm reduction practice that provides chemical analysis of substances. This is not only to inform harm reduction for people who use, buy and sell drugs (and those who support them), but also to monitor the supply for emerging trends that inform both the community and policymakers about the state of the unregulated supply, which remains volatile, unpredictable and dangerous.

As researchers providing drug checking on Vancouver Island, we see value in exploring new ways to deliver this service to reach more people who use drugs, at a scale required to address the current crisis.

Drug checking in global perspective

While drug checking has been around since the 1990s, it remains an underused intervention that is often limited in both scope and scale. However, innovations in how and where the service is provided, as well as technological advancements within analytical chemistry and instrumentation, are helping to overcome these limitations.

Internationally, groups like the Drug Information Monitoring System in the Netherlands have been pioneering drug checking and continuing to inform drug-checking research and practice internationally.

While services in some countries remain beholden by archaic prohibitory legislative environments that challenge the legality of drug checking, others are finding success in embedding drug checking within novel legal frameworks, like the legalization of drug checking in New Zealand.

Drug checking in Canada

In Canada, drug checking has its origins in the festival and rave scene as a grassroots bottom-up response to the harms of an unregulated market. The oldest drug-checking project has provided critical services at Shambhala Music Festival in Salmo, B.C. for the last two decades.

The success of drug checking in festival settings for lowering potential harms and highlighting broader trends is now increasingly being evaluated as a response to the overdose crisis in B.C. and other parts of the country.

Drug checking alone is not enough to curb the dramatic increase in drug toxicity deaths in the province and nationally. However, some of its strengths include generating evidence of trends within the drug supply, as well as evidence for its effectiveness as a harm-reduction measure. It can also be incorporated into other harm reduction programs and methods, including safe supply.

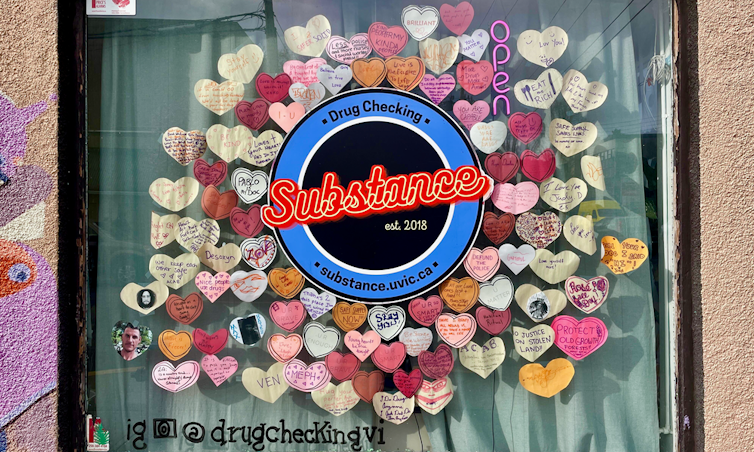

Substance: The Vancouver Island drug-checking project

Our research-based service in Victoria, B.C. has spent the last five years developing and evaluating drug-checking service models while conducting robust multi-disciplinary research in the fields of social work, chemistry, computer science and public health. This research provides evidence to support services that respond to the unique needs of people accessing drug-checking services.

On the chemistry side, our research evaluates and improves analytical technologies and methods, and boosts their effectiveness in detecting fentanyl and other adulterants. Public health research highlights how drug checking goes beyond individualistic responses to act within community, market and policy arenas. This research supports services that respond to the unique needs of people accessing drug-checking services.

Vancouver Island’s unique model of drug checking

In responding to the challenges of scaling up drug-checking services, we developed a unique distributed drug-checking model to increase the reach of these services.

This model aims to fill in gaps in service delivery for diverse communities that are vulnerable to the unregulated drug supply. It also highlights the importance of multidisciplinary research and service design that draws critical insight from multidisciplinary fields to better inform drug-checking services.

Drawing on a network that enables the collection of samples in various locations and communities, our distributed model provides a hybrid, easy-to-use drug-checking program. The program blends immediate portable drug-checking technologies for timely harm reduction with more comprehensive lab-based technologies that provide greater accuracy of drug composition.

Through the use of specialized spectrometers and test strips distributed at various sites and connected to a central server and database, drug analysis can be done remotely within our central hub. These results get looped back to service users distributed across Vancouver Island who also have the opportunity to receive further analysis at a later time using a lab-based method called paper spray mass spectrometry.

This model responds to the unique challenges of providing critical harm reduction across geographical locations and within different communities. Through the distributed model, we continue to evaluate what works best for whom in the context of an ever-changing drug supply and policy landscape.

Most consumables in Canada have quality controls that help inform purchasing and consumption decisions. People who use drugs and those who support them deserve the same. It is long past time that we respond to the enduring crisis to the magnitude it deserves.

Drug checking everywhere for everyone: is it possible? It is certainly a worthwhile goal with life-saving potential, and we will continue working to achieve it.

Bruce Wallace received funding from Health Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, Vancouver Foundation, and the Island Health Authority.

Dennis Hore received funding from Health Canada, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Piotr Burek does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.