A new investigation of data collected by NASA's Cassini mission, which ended six years ago, has revealed that the spacecraft spotted a key ingredient needed for life on Saturn's icy moon Enceladus. The Cassini observations have revealed a powerful energy source for potential lifeforms deep below the icy shell of this moon.

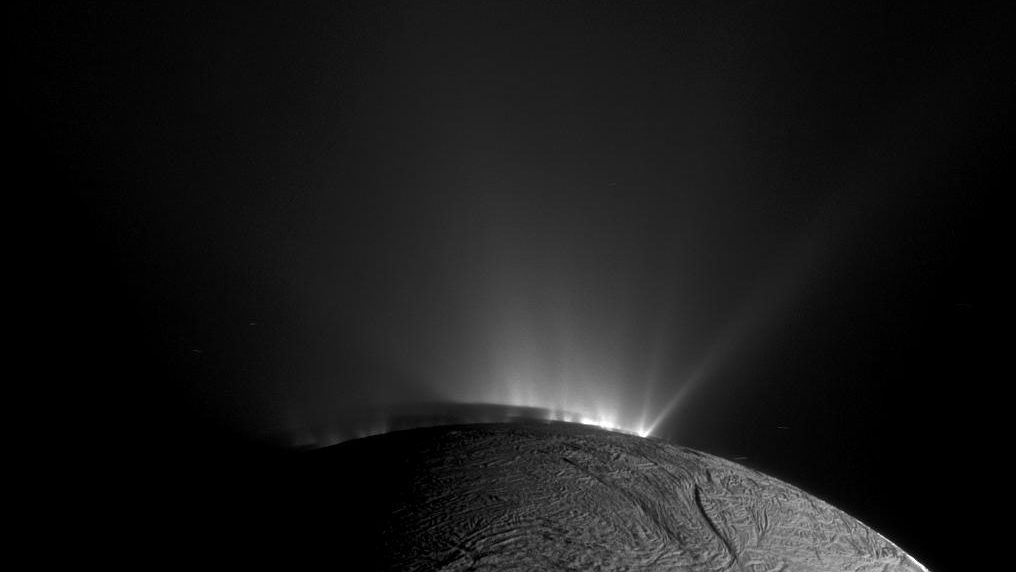

Enceladus blasts out plumes of ice and water from fissures in its icy shell, and scientists have known for some time that organic molecules — some of which may have the right chemistry to be important for life as we know it — are contained in these jets. In 2017, scientists found carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen in Enceladus' plumes, indicative of a metabolic process called methanogenesis. As its name suggests, methanogenesis produces methane, which is widespread here on Earth and could be a sign of life on other worlds.

The new confirmation of hydrogen cyanide — a crucial precursor for some molecules that needed to be present on Earth for life to arise — takes the concept that Enceladus could be habitable to a whole new level, however.

The same research team also discovered that the subsurface ocean of Enceladus, from which the plumes apparently originate, could be the source of several other organic compounds, some of which serve as fuel sources for terrestrial organisms. This indicates that there may be more energy available for life on Enceladus than was previously thought.

"Our work provides further evidence that Enceladus is host to some of the most important molecules for both creating the building blocks of life and for sustaining that life through metabolic reactions," lead author and Harvard University doctoral student Jonah Peter said in a statement. "Not only does Enceladus seem to meet the basic requirements for habitability, we now have an idea about how complex biomolecules could form there, and what sort of chemical pathways might be involved."

The Swiss Army Knife of life

To get started, life as we know it needs compounds like amino acids as its essential building blocks. The team behind the new findings describes hydrogen cyanide as the Swiss Army Knife of amino acids because of the variety of ways the molecule can be stacked to help construct amino acids.

"The discovery of hydrogen cyanide was particularly exciting, because it's the starting point for most theories on the origin of life," Peter said. "The more we tried to poke holes in our results by testing alternative models, the stronger the evidence became. Eventually, it became clear that there is no way to match the plume composition without including hydrogen cyanide."

This newfound source of chemical energy is more powerful and diverse than the methanogenesis process, study team members said. This means that there are various chemical pathways available for organisms (if they exist) in the moon's subsurface ocean.

"If methanogenesis is like a small watch battery, in terms of energy, then our results suggest the ocean of Enceladus might offer something more akin to a car battery, capable of providing a large amount of energy to any life that might be present," research co-author Kevin Hand, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California, said in the same statement.

The team used statistical analysis to arrive at their results. Armed with the new findings; scientists can now investigate these chemical pathways for life in the lab as they attempt to discover if Enceladus really has the right stuff for life.

"We used math and statistical modeling to figure out which combination of puzzle pieces best matches the plume composition and makes the most of the data without overinterpreting the limited dataset," Peter said. "There are many potential puzzle pieces that can be fit together when trying to match the observed data."

The research also demonstrates that the Cassini mission keeps delivering important insights about Saturn and its moons, despite having made a suicide dive into the atmosphere of the gas giant in September 2017.

"Our study demonstrates that while Cassini's mission has ended, its observations continue to provide us with new insights about Saturn and its moons — including the enigmatic Enceladus," said Cassini team member Tom Nordheim, also of JPL.

The team's research was published on Thursday (Dec. 14) in the journal Nature Astronomy.