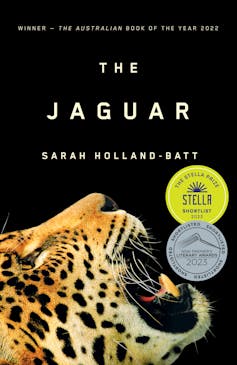

Acclaimed poet Sarah Holland-Batt has won the 2023 Stella Prize for her powerful and elegiac collection of poetry, The Jaguar.

Poetry was excluded from the Stella Prize until 2022. In only the second year of its inclusion, poetry has made its presence known: Holland-Batt is the second poet in a row to win the prize, after last year’s was won by Evelyn Araluen’s collection, Dropbear.

And poetry seems to be more widely on the ascendant in Australia: in January, it was announced that from 2025, Australia will have a national Poet Laureate. Holland-Batt read a poem from The Jaguar at the announcement.

Read more: Australia is to have a poet laureate – how will the first appointment define us as a nation?

The full power of poetic language

The Jaguar is Holland-Batt’s third collection of poetry, and the $60,000 Stella Prize joins a string of previous accolades – most notably the 2016 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for her 2015 collection The Hazards.

The Jaguar brings the full power of poetic language to bear on experiences often pushed to the edges of public life. The most stunning poems in the collection focus on the experience of ageing, illness and death – in ways that are both deeply compassionate and fierce.

Stella Prize chair Alice Pung says of the book:

In The Jaguar, Sarah Holland-Batt writes about death as tenderly as we’ve ever read about birth. She focuses on the pedestrian details of hospitals and aged care facilities, enabling us to see these institutions as distinct universes teeming with life and love.

Her imagery is unexpected and unforgettable, and often blended with humour. This is a book that cuts through to the core of what it means to descend into frailty, old age, and death. It unflinchingly observes the complex emotions of caring for loved ones, contending with our own mortality and above all – continuing to live.

The politics of bearing witness

Stella’s winning books have tended to have an activist dimension – and The Jaguar is no exception. In paying such careful attention to the long decline and death of Holland-Batt’s father from Parkinson’s Disease, this collection can be considered an extension of her advocacy about human rights abuses in aged care in Australia.

Holland-Batt has spoken publicly about the neglect of aged care funding and policy in this country. She made a submission to the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety about the abuse and neglect her father suffered in aged care.

“Because we vehemently resist thinking about ageing and death, talking about these subjects openly is difficult or even taboo,” she wrote in the Sydney Morning Herald last year. “Our cultural denial of death also underwrites many of our failures in aged care.”

The politics of this collection reside in the act of bearing witness. In these poems, the mundane world of the hospital and nursing home takes on a glowing life, with the natural world interleaving and sometimes crashing into the cloistered worlds of illness and death in hospital waiting rooms and corridors.

The brilliant opening poem envisions the speaker’s father as a giant koi, “guiding the mottled zeppelin / of his body in a single unceasing turn”, surfacing when the nurses bring his dinner.

In another poem, the speaker’s mother is in hospital, listening to David Attenborough, and the ward and the world of his documentary become entangled: “Buzzers / zip and sting like electric / whipbirds.” These poems are moving and surprising, full of inventiveness and sound play.

There are some vertiginous tonal shifts across this collection. Readers are taken from hospital elegies to a world of champagne, travel and sex. These shifts can be discomforting because much of the collection, including its first section, uses a traditionally lyric voice: an “I” which in this case can easily be aligned with the experiences and perspective of the poet herself.

This makes the poems easy for the reader to get a handle on and to understand what is at stake in them. When the reader gets to poems that take on a more satirical or playful tone, such as “Affidavit”, the speaking “I” is much less stable: the reader needs to work harder to understand what is going on.

Read more: How to complain about aged care and get the result you want

Imaginative flight

A good example of these shifts is in the ways the jaguar of the collection’s title emerges throughout the collection. The hyperbolic “Ode to Cartier”, which reanimates images of jewellery advertising to unsettling life, reads: “let me die in peace / with the silk of a jaguar’s breath / huffing in my ear at dawn.”

Elsewhere we see a father raise a cup of jaguar’s blood on an impossible trip to Brazil. Another jaguar is given as a pet by a drug dealer to his daughter. And finally, the titular poem in which the Jaguar transmogrifies from imagined animal to actual car, “a folly he bought without test-driving, / vintage 1980 XJ, a rebellion against his tremor.”

This “bottle green” jaguar exemplifies the grief and rage and lost possibilities embodied in a diagnosis like Parkinson’s. It is driven, dangerously and against doctor’s orders, then tinkered with until finally “it sat like a carcass / in the garage, like a headstone, like a coffin – / but it’s no symbol or metaphor. I can’t make anything of it.”

The jaguar of this poem also demonstrates Holland-Batt’s imaginative and linguistic power: it is at once an object of this world and a link to other understandings of the relationship between the human and the animal, especially at death.

With a combination of ruthlessness and tenderness, clear-eyed witness and imaginative flight, this is a poet who knows exactly what she is doing.

Julieanne Lamond receives funding from the Australian Research Council. She has undertaken research, with Melinda Harvey, for the Stella Count.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.