If Aaron Hawkins is stuck for ideas to include in the Green Ōtepoti campaign launch this week, Philip Temple, Rosemary Penwarden, Sir Alan Mark and Olivier Jutel offer some suggestions that he’s free to take up

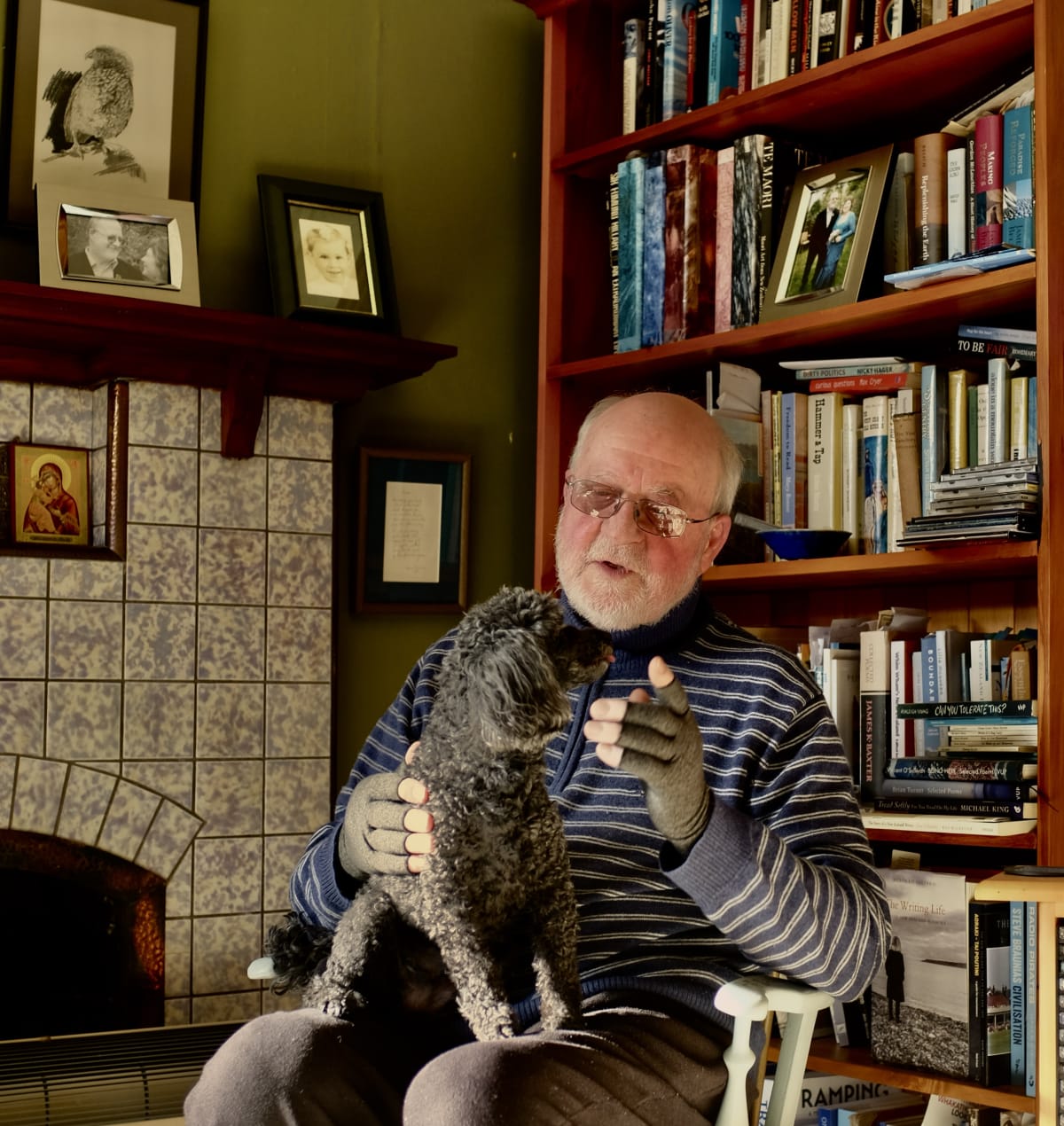

Before Ōtepoti Dunedin mayor Aaron Hawkins and councillor Marie Laufiso outline their Green vision for the city on Wednesday, long-time greenie Philip Temple would willingly bend their ears. Whether they would listen is another thing.

Temple, a writer, one-time mountaineer and climate campaigner, feels excluded by today’s Green Party.

“I’ve always been green and I’m also a bit of a socialist. But the Green Party seems to be leaving me behind – I know, I’m 83."

Identity issues are sidetracking them, he believes.

“Some of the changes that are taking place seem to leave me out of the discussion as an older, white, straight male.”

In May, the party changed its constitution to no longer require both female and male co-leaders, but specifying one be female, the other any gender and one Māori.

“I have nothing against LGBTQ at all – everyone has rights – but most of these questions have already been settled.

“And especially now, with pressures developing through climate change, limits to growth, the economic crisis and the Ukraine war, we have to shift our focus back to being together as a community of all stripes.”

Temple, a £10 pom whose connection to the New Zealand outdoors springs from decades climbing in the Southern Alps, can’t claim to have been present at the conception of the Green Party of Aotearoa. But he was part of the team that ensured it didn’t have a still birth.

With legendary Green Rod Donald, Temple was active in the pro-MMP campaign. After a series of debates with backers of first-past-the-post, mixed-member proportional won the day in a binding 1993 referendum.

“We ended up back at the hotel after the last live television debate and Donald said to me, ‘If we win, what are you going to do? I have to make up my mind whether to join the Labour Party or the Greens.’

“I told him he was obviously a Green.”

Donald became a party founder and, as part of the Alliance, landed one of two Green seats in the first MMP election. He was Greens co-leader until his death in 2005.

Temple, feeling battered by the campaign’s nastiness, vowed to have nothing more to do with politics.

He has, however, remained active in his advocacy of environmental issues, these days as part of Wise Response, a group that includes scientists, academics, writers, ex-mayors and a former All Black who attempt to bring pressure to bear on Parliament to do something about climate change.

Although a champion of community, his prescription in the face of the world’s woes is greater self-reliance, which he thinks his home city of the past 30 years could exemplify.

“Dunedin is the perfect small city. With its size and population, it is ideally configured to be self-sufficient, and my feeling is that’s where the future is.”

Woman of action

Rosemary Penwarden, a long-time campaigner against the burning of fossil fuels, also thinks Dunedin could have a unique response to climate change. Her own commitment – she faces charges for stopping a train last December that was carrying coal to a Fonterra milk-powder plant and also spent more than $20,000 converting her 1993 petrol-burning Honda car to battery power – is clear to see.

“For a long time I’ve been trying to put things into a wider context, which is pretty overwhelming. It’s hard to see what we can do in our small part of the world that is going to be useful.

“This is a massively changing time - I’m talking about the climate breakdown, which we can see happening in real time - and the mayor is pivotal among public-office holders in taking a lead.”

In Ōtepoti, the most pressing climate-related problem is the repeated flooding of South Dunedin. The city council and Otago Regional Council are collaborating on South Dunedin Future, a flooding mitigation plan made public on July 5 to a generally positive reception.

Penwarden believes this is Hawkins’ opportunity to make his mark.

“The best thing the council can do is put important decisions - such as the future of South Dunedin - into the hands of the people via something like a citizens’ assembly.”

She points to Ireland’s use of a citizens’ assembly in 2017 to grapple with the issue of abortion, which the Catholic church had ensured remained illegal since the 1860s. The assembly, made up of randomly selected members of the public, debated the question after hearing from expert witnesses. They recommended the law be changed, which was supported by a referendum the following year.

“South Dunedin flooding is the big one. I think the council is finding a way through that and the mayor I want is someone who is clearly recognised by ordinary people and is out there talking to them.

“The days are gone when the people with big money and financial interests get the most say. That’s what I would like to see.”

Penwarden is a member of the Greens but says the party can’t take her vote for granted, which she communicated recently to MP Golriz Ghahraman. “I told her ‘I need a good reason to vote for you guys at the moment’.”

Her hesitation comes from the Greens’ apparent willingness to support the Labour government on the Ukraine war, when she feels questions need to be asked about the environmental costs of the conflict.

“It is the last moment in history when we need something like this. But it is a long way from the mayoralty.”

Despite her reservations about the Greens on the national stage, she does think a mayor of that hue “is streets ahead” when it comes to change at a civic level. “Neo-liberalism has got us into this mess. We need a more collaborative model and I think the Greens have policies to take us in the right direction.

“But I will keep pushing them because I don’t think they’re doing enough.”

Penwarden is not in the mayor’s inner circle but she is pleased to be on the same page as him - literally - in regard to offshore oil drilling. The Otago Daily Times quoted Hawkins and Penwarden in a story in February last year welcoming news that the South Island’s last oil and gas exploration permit was unlikely to be taken up.

“I’m pleased we’re on the same page because he does call himself a Green mayor. So that’s a good thing.”

Still making a mark

The climate crisis ensures plenty of column centimetres are given over to environmental issues, but there’s nothing new in that in this country.

In the early 1970s, a headline-grabbing battle was fought on the shores of Lake Manapōuri in Fiordland. It was sparked by a proposal to raise the lake by 27m as part of the hydro scheme built to supply electricity to the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter, proving that power-hungry plant is no stranger to headlines either.

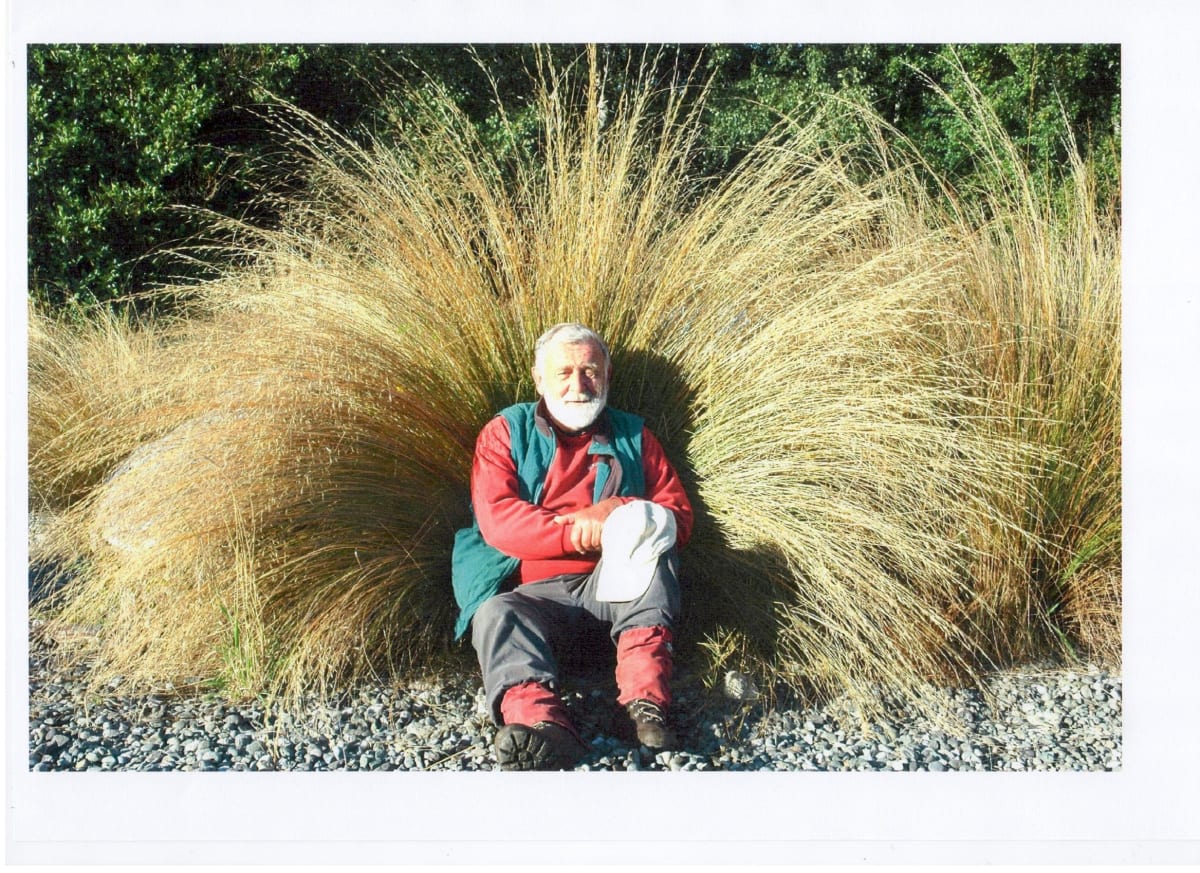

University of Otago botanist Alan Mark (now Sir Alan), who was asked by the Government to advise on how a raised lake would affect the forested shore, went further and became a founding member of the Save Manapōuri campaign. With the help of a petition signed by more than 250,000 people, the lake was saved.

Mark, who is 90, is still fighting the good fight as a member of Wise Response. But he is a political pragmatist, acknowledging that however green a mayor may be, they can only do what their council lets them.

“A mixed bag of councillors keeps a Green mayor from showing his true colours,” he says.

As an urgent response to climate change, Mark advocates Ōtepoti move to reduce carbon emissions.

“One way of doing that might be free public transport.”

Last November, the council backed a nationwide call for the government to provide free fares for people with a Community Services Card, those aged under 25 and all tertiary education students.

With its own money, it is spending up large on bike paths - tens of millions of dollars, alongside Waka Kotahi, for harbour-edge shared cycle and pedestrian paths and millions more for planned Mosgiel and North Dunedin routes.

“That is also a response to reducing global warming and reducing carbon emissions,” Mark says. “But I must say there’ve been a few cock-ups in the planning and execution of those and costs have escalated beyond what might have been expected.”

Aside from rates, Dunedin pulls in millions of dollars - about $80 million since 1990 - from 20,000ha of council-owned pinus radiata plantations. Mark would like to see City Forests, which owns the trees, diversify into california redwoods, a longer-lived species that is better for carbon sequestration.

“Pinus radiata plantations are reasonably positive in terms of carbon sequestration, but with its 28-year cycle, that species can only take a certain amount of carbon out of the atmosphere. And once it’s harvested, it’s the fate of the wood that determines the fate of the sequestered carbon.

“The california redwood lasts for a 1000 years-plus so has more going for it, although they say it is more appropriate for the North Island than the south. But there are some impressive redwoods in the Pine Hill catchment and across the town belt.”

Despite the limitations on what the mayor can accomplish, Mark is supportive of him.

“Dunedin’s councillors certainly represent a wide range of views. I’d be sympathetic to Hawkins in terms of what he’s been able to achieve as a Green mayor knowing that he has to be adjudicator and draw a compromise among the views that are expressed.”

Got his skates on

Olivier Jutel is frank about his and Hawkins’ relationship going a long way back. In 2014, when Hawkins was the breakfast host on student station Radio One, Jutel was the programme director, and they had known each for years already. He calls him a close personal friend.

“Hawkins was the person at work who would be watching Parliament TV,” says Jutel, a communications lecturer at the University of Otago who teaches a paper in urban studies.

As a Dunedin Skateboarding Association member and an advocate of new urbanism, Jutel has worked on submissions on the city’s 10-year plans.

“We care about the local political debates around pedestrians, liveable cities and that kind of stuff. Hawkins is one of those guys.

“He is green, and that’s about resiliency, but it’s also about the politics of new urbanism. That’s a big cultural clash with, I suppose, suburban Fairfield, Taieri and the folks who want car parks.”

Jutel is happy to trade on the fact Dunedin has a Green mayor.

“It’s one of those things that makes us feel good about our self-image. I have friends in Auckland and Wellington who say, ‘Oh, Dunedin is such a cool city, it has a Green mayor,’ much as a lot of my international friends talk about New Zealand because of Jacinda Ardern.

“It’s a good export image of Dunedin as a progressive, cosmopolitan small town with a university, history and arts and culture.”

For Jutel, the way Dunedin dealt with a long-running anti-vax encampment in the central-city Octagon exemplifies the city’s -and mayor’s - measured approach to civic challenges.

“The view was, ‘This is the cost of democracy, we’ll be cool about it,’ and it dissipated. That was very nicely managed.

“He’s pragmatic and a believer in consensus debate, the core civic processes that underpin these institutions. He is not a revolutionary.”

If Hawkins sticks with the programme, Jutel is sure Ōtepoti will be seeing more of him.

“I think he’s done incredibly well and I think he’ll win re-election. There may be some populist culture-war headwinds, but I don’t think they really threaten Hawkins.”

* Made with the support of the Public Interest Journalism Fund