What will the diets of the future look like? The answer depends in part on what foods Westerners can be persuaded to eat.

These consumers are increasingly being told their diets need to change. Current eating habits are unsustainable, and the global demand for meat is growing.

Recent years have seen increased interest and investment in what are called alternative proteins – products that can replace typical meats with more sustainable alternatives. One option is cultivated, or cultured, meat and seafood: muscle tissue grown in labs in bioreactors, using animal stem cells. Another approach involves replacing standard meat with such options as insects or plant-based imitation meats. All of these products promise a more sustainable alternative to factory-farmed meat. The question is, will consumers accept them?

I’m a philosopher who studies food and disgust, and I’m interested in how people react to new foods such as lab-grown meat, bugs and other so-called alternative proteins. Disgust and food neophobia – a fear of new foods – are often cited as obstacles to adopting new, more sustainable food choices, but I believe that recent history offers a more complicated picture. Past shifts in food habits suggest there are two paths to the adoption of new foods: One relies on familiarity and safety, the other on novelty and excitement.

Disgust and the yuck factor

Disgust is a strong feeling of revulsion in response to objects perceived to be contaminating, polluting or unclean. Scientists believe that it evolved to protect human beings from invisible contaminants such as pathogens and parasites. Some causes of disgust are widely shared, such as feces or vomit. Others, including foods, are more culturally variable.

So it’s not surprising that self-reported willingness to eat insects varies across nationalities. Insects have been an important part of traditional diets of cultures around the world for thousands of years, including the ancient Greeks.

Many articles about the possibility of introducing insects to Western or American diners have emphasized the challenges posed by neophobia and “the yuck factor.” People won’t accept these new foods, the thinking goes, because they’re too different or even downright disgusting.

If that’s right, then the best approach to win space on the plate for new foods might be to try to make them seem similar to familiar menu items.

The safe route to food acceptance

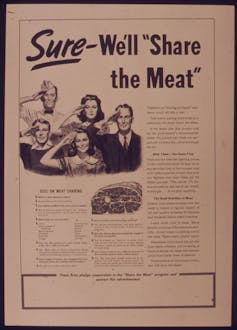

During World War II, the United States government wanted to redirect its limited meat supply to troops on the front lines. So it needed to convince home cooks to give up their steaks, chops and roasts in favor of what it called variety meats: kidneys, liver, tongue and so on.

To figure out how to shift consumer habits, a team of psychologists and anthropologists was charged with studying how food habits and preferences were formed – and how they could be changed.

The Committee on Food Habits recommended stressing these organ meats’ similarity to available, familiar, existing foods. This approach – call it the “safe route” – focuses on individual attitudes and choices. It tries to remove psychological and practical barriers to individual choice and counteracts beliefs or values that might dissuade people from adopting new foods.

As the name suggests, the safe route tries to downplay novelty, using familiar forms and tastes. For example, it would incorporate unfamiliar cuts of meats into meatloaf or meatballs or grind crickets into flour for cookies or protein bars.

The sushi route

But more recent history suggests something different: Foods such as sushi, offal and even lobster became desirable not despite but because of their novelty and difference.

Sushi’s arrival in the postwar U.S. coincided with the rise of consumer culture. Dining out was gaining traction as a leisure activity, and people were increasingly open to new experiences as a sign of status and sophistication. Rather than appealing to the housewife preparing comfort foods, sushi gained popularity by appealing to the desire for new and exciting experiences.

By 1966, The New York Times reported that New Yorkers were dining on “raw fish dishes, sushi and sashimi, with a gusto once reserved for corn flakes.” Now, of course, sushi is widely consumed, available even in grocery stores nationwide. In fact, the grocery chain Kroger sells more than 40 million pieces of sushi a year. Whereas the safe route suggests sneaking new foods into our diets, the sushi route suggests embracing their novelty and using that as a selling point.

Sushi is just one example of a food adopted via this route. After the turn of the millennium, a new generation of diners rediscovered offal as high-end restaurants and chefs offered “nose to tail” dining. Rather than positioning foods like tongue and pigs’ ears as familiar and comforting, a willingness to embrace the yuck factor became a sign of adventurousness, even masculinity. This framing is the exact opposite of the safe route recommended by the Committee on Food Habits.

The future of alternative proteins

What lessons can be drawn from these examples? For dietary shifts to last, they should be framed positively. Persuading customers that variety meats were a necessary wartime substitution worked temporarily but ultimately led to the perception that they were subpar choices. If cultivated meat and insects are pitched as necessary sacrifices, any gains they make may be temporary at best.

Instead, producers could appeal to consumers’ desire for healthier, more sustainable and more exciting foods.

Cultivated meat may be “safe-ly” marketed as nuggets and burgers, but, in principle, the options are endless: Curious consumers could sample lab-grown whale or turtle meat guilt-free, or even find out what woolly mammoth tasted like.

Ultimately, the chefs, consumers and entrepreneurs seeking to remake our food systems don’t need to choose just one route. While we can grind insects into protein powders, we can also look to chefs cooking traditional cuisines that use insects to broaden our culinary horizons.

Alexandra Plakias does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.