On July 8, Canada’s Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly announced new sanctions against Russia as a counter to the Kremlin’s disinformation activities aimed at Canada.

Ukraine and the West have long been a target of the Kremlin’s disinformation campaigns. Since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia has used a variety of information warfare tactics to destabilize the Ukrainian government and undermine the legitimacy of democratic governments around the world.

In recent years, as part of its bid to shape public perception of their action on the world’s stage, Russia has deployed an army of bots, trolls, hackers and other proxies across social media and the internet. These tactics are being used as a part of a concerted effort to curate a more favourable information environment for their agenda in Ukraine and other areas of geopolitical interest.

In the lead up to the 2016 U.S. federal election, the Kremlin used the now infamous “Internet Research Agency” to sow discord online and off-line.

Online warfare tactics

Since the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February, the Social Media Lab’s Conflict Misinformation Dashboard has tracked over 1,000 false, misleading and unproven claims. Some of these false and misleading claims were spread by Russian government officials and their proxies. For example, in the early months of the war, the Kremlin was actively spreading the unsubstantiated claim that chemical and biological weapons are being covertly developed in Ukraine.

And Canada’s Communications Security Establishment has raised concerns about Russian online state-sponsored disinformation campaigns aimed at distorting Canada’s effort to help Ukraine defend itself.

Read more: Conspiracy theorists are falsely claiming that the coronavirus pandemic is an elaborate hoax

As part of our ongoing research into how misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories spread online, we conducted a survey in May 2022 to examine the extent to which Canadians are exposed to, and might be influenced by, pro-Kremlin propaganda on social media. Among other questions, we asked participants about their social media use, news consumption about the war in Ukraine, political leanings as well as their exposure to and belief in common pro-Kremlin narratives.

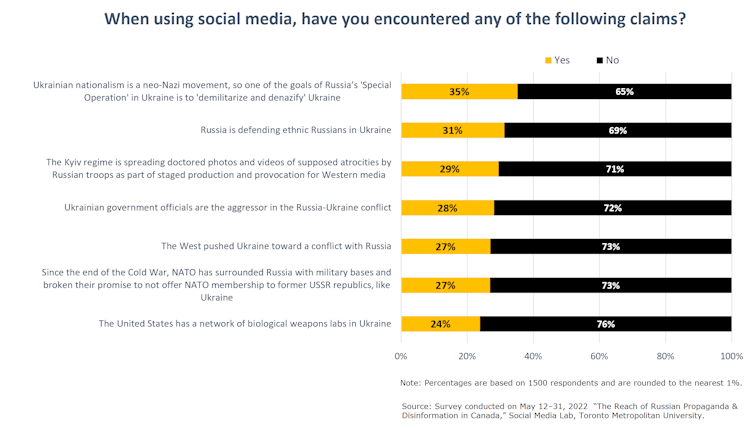

The data we collected shows that Canadians are being exposed to pro-Kremlin propaganda. Slightly over half of Canadians (51 per cent) reported encountering at least one persistent, false claim about the Russia-Ukraine war on social media pushed by the Kremlin and pro-Kremlin accounts.

The most prevalent claim, encountered by 35 per cent of Canadians, was “Ukrainian nationalism is a neo-Nazi movement,” a false narrative that has long been debunked by numerous fact-checkers.

However, it is the claim about NATO expansion that gained the most traction with the Canadian public. Specifically, nearly half of Canadians (49 per cent) believed at least to some extent that “since the end of the Cold War, NATO has surrounded Russia with military bases and broken their promise to not offer NATO membership to former U.S.S.R. republics, like Ukraine.”

Pro-Kremlin propaganda

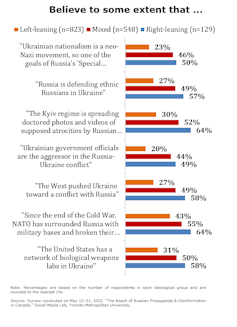

Next, we looked for a connection between political ideology and people’s propensity to believe in pro-Kremlin propaganda. We used the Ideological Consistency Scale developed by the Pew Research Center. The scale is designed to determine one’s political ideology on a scale between -10 (mostly liberal) to +10 (mostly conservative). It is based on 10 questions about social issues, military and homosexuality, which correlate with a traditional left/right political affinity.

Our analysis shows that left-leaning Canadians are consistently less likely to believe in pro-Kremlin propaganda overall, as compared to Canadians who hold mixed or right-leaning views. Conversely, those who hold right-leaning ideologies are more likely to believe in pro-Kremlin propaganda overall, as compared to Canadians who hold mixed or left-leaning views.

Reliance on social media

Another important factor that we found to be associated with belief in pro-Kremlin disinformation was a preferred source for getting news about the Russia-Ukraine war. Particularly concerning is the fact that those who believe in one or more of the pro-Kremlin claims are more likely to rely on social media for news about the war than those who do not believe in any.

For instance, 57 per cent of Canadians who believe the claim that “Ukrainian nationalism is a neo-Nazi movement” reported preferring social media as a source of news about the Russia-Ukraine war. In contrast, only 23 per cent of those who do not believe in this claim favour social media when accessing news on this topic.

This stark difference in social media consumption between those who believe versus those who don’t believe in this and other persistent claims stresses the importance of doubling down on efforts to combat misinformation in online spaces, especially misinformation seeded by foreign adversaries.

The perils of pro-Kremlin propaganda are real, and we should not underestimate its potential to shape public perception in Canada. The aim of an information operation is not necessarily to make everyone believe. It is often sufficient to sow doubt and confusion, as well as to delay or derail consensus amongst one’s adversaries, their allies and bystanders.

Our research provides evidence that the Kremlin’s disinformation is reaching more Canadians than one would expect. Left unchallenged, state-sponsored information operations can stoke tensions and undermine democracy.

Anatoliy Gruzd's research is supported in part by funding from the Canada Research Chairs program and the Tri-Council funding agencies.

Alyssa N. Saiphoo, Felipe Bonow Soares, and Philip Mai do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.