With the Arab spring of 2011, a downturn in tourism and the devastation of COVID, the odds have been stacked against the opening of Giza’s Grand Egyptian Museum, work on which began in 2005 and is due to complete 2023.

Nevertheless, it will house over 100,000 artefacts and become the largest archaeological museum complex in the world. It is sure to draw millions of visitors to see the most complete story yet of ancient Egypt, told by Egyptians.

Highlights will include the entirety of Tutankhamun’s treasure, displayed together for the first time. However, as dazzling as this will be, it is unlikely to completely distract from the ever-present repatriation debate.

In fact, the museum’s opening looks set to mark a turning point in the academic debate around returning its most obvious missing artefact – the Rosetta Stone – to Egypt.

The case against repatriation

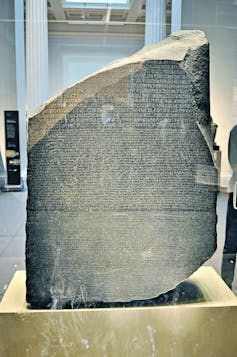

The Rosetta Stone has been the subject of a lengthy repatriation campaign. Rediscovered in 1799 by the French military campaign in the Egyptian Delta, following Napoleon’s defeat by the British, the stone was shipped to England in 1802. It has been on display at the British Museum ever since.

The British Museum has maintained a steady resistance to the stone’s return to Egypt. Legislation, including the British Museum Act 1963 (which prevents the British Museum from disposing of its holdings), covers its legal right to the stone. But there is now increasing pressure to return it to Egypt as a gesture of goodwill, recognition of the stone as Egypt’s cultural property and a symbol of a country that is increasingly reclaiming its heritage.

Some academics maintain that the stone should stay in London. There, they argue, more visitors will see it, and it takes pride of place among artefacts representing the collective efforts of humanity. They also highlight that the British Museum has kept it safe for two centuries and without British and French efforts, the stone’s significance would remain unknown.

For many years, one of the main academic arguments questioned the suitability of the Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, Cairo, as a home for the Rosetta Stone.

The case for repatriation

The argument that the stone is safer from a conservation perspective in the British Museum no longer carries the same weight in light of the new Grand Egyptian Museum, which now houses many objects formerly in Tahrir Square.

Ironically, the infrastructure of the British Museum is also in need of upgrading and refurbishment. The next few years will see this work commence in a radical overhaul called, appropriately, the “Rosetta Project”.

The British Museum positions itself as a repository of world culture, and there is certainly a case to be made for a more inclusive cultural heritage network. It can be argued that the Rosetta Stone is also part of British and French history, due to the decipherment success by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, but in the end, it may come down to perceptions.

To some Egyptians, the stone is a symbol of colonialism, and the British Museum’s retention of it signals that the western dominance of Egyptian archaeology is still present. The British Museum, understandably, does not wish to relinquish its star object, but the pressure may eventually make its position untenable.

As one of the world’s most high-profile museums, its decisions are in the spotlight and any change in its stance on the Rosetta Stone could lead to other institutions being approached about the repatriation of Egyptian collections.

This year, more than 2,500 archaeologists signed a petition to repatriate the stone and, in 2021, a YouGov poll on the wider issue of returning artefacts to their country of origin found 62% in favour.

Implications for worldwide heritage

The British Museum has stated that they have received no formal request for the return of the Rosetta Stone, but as the 1963 Act prevents its return, the most logical way forward is the establishment of a partnership with Egypt’s Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

George Osborne’s position as chair of the British Museum is that the strength of the collection is in the representation of common humanity, but that the museum is willing to enter into a dialogue to ensure a satisfactory outcome for all parties.

However, as ownership will still reside with the British Museum, advocates for the stone’s return may feel this does not go far enough. On the other hand, there is a concern about the potential for cultural regression if museums start to divide their collections, although the likelihood of having to empty stores is small.

The Rosetta Stone is a perfect example of the continuing biographies of objects. Its significance no longer rests only on its role in the decipherment of hieroglyphs, and 18th- to 19th-century relationships between Britain, France and Egypt. It has taken on new meaning, and its importance now is as a symbol of the decolonisation debate, and of Egypt itself.

Claire Gilmour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.