Ron DeSantis has broken his silence on allegations that he observed the force-feeding of detainees at Guantanamo Bay during his time serving as a Navy lawyer there.

The Independent reported last week on claims by a former prisoner of the prison camp, Mansoor Adayfi, that Mr DeSantis observed his brutal force-feeding by guards during a hunger strike in 2006 – a practice the United Nations characterised as torture.

Mr DeSantis was stationed on the base between March 2006 and January 2007, according to his military records, and part of his role involved hearing complaints and concerns from prisoners over their conditions.

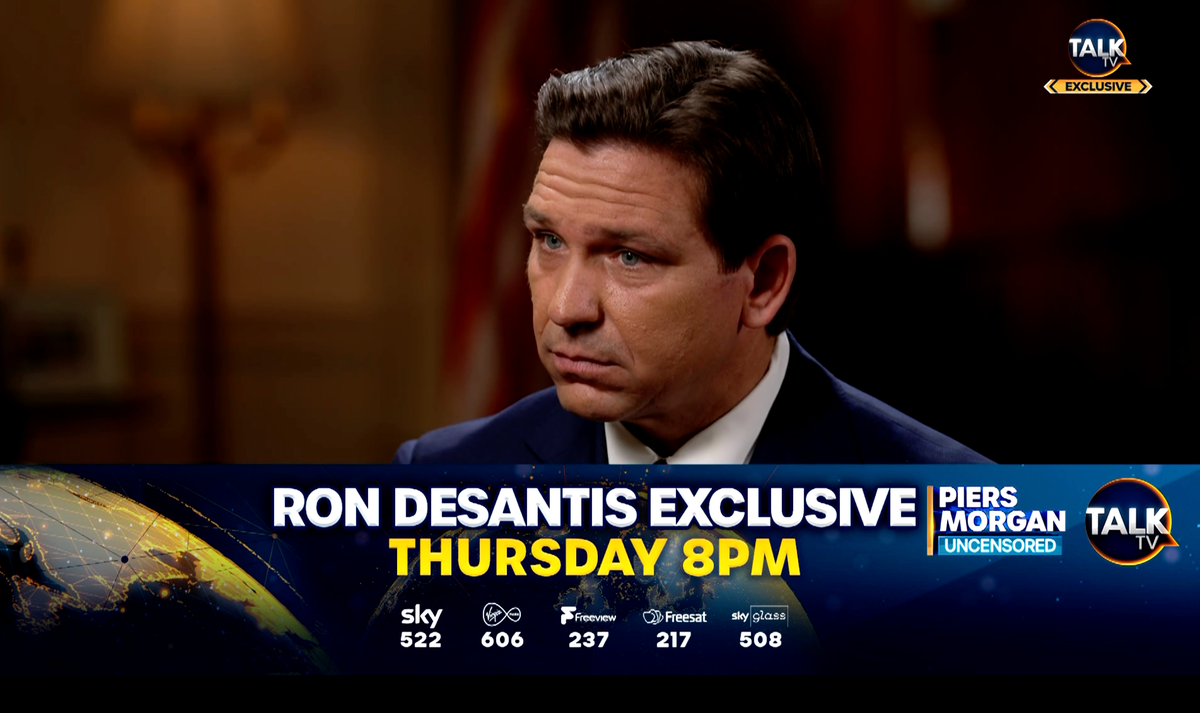

“I was a junior officer. I didn’t have authority to authorise anything,” Mr DeSantis told Piers Morgan, in an interview to be broadcast on Thursday.

“There may have been a commander that would have done feeding if someone was going to die, but that was not something that I would have even had authority to do.”

The Florida governor’s response did not address the central allegation from the detainee that he witnessed the force-feeding. Investigations by The Independent, The Washington Post and other outlets did not report that Mr DeSantis authorised the force-feeding – rather, that he observed and was aware of the practice.

Mr DeSantis has not responded to several requests from The Independent for comment on the allegations and for clarity about his role in the notorious prison camp.

As an assumed candidate for the 2024 election, Mr DeSantis is likely to face questions about this time in his career and what impact – if any – witnessing the treatment of Guantanamo detainees has had on his politics.

Until now, he has not spoken in detail about this part of his career. In public, he has advocated for the continued use of Guantanamo Bay to hold detainees suspected of involvement of terrorism, but he has not spoken in detail about his time at the camp.

The US government has denied that force-feeding hunger strikers amounts to torture, and it has been used against prisoners over successive administrations during hunger strikes.

In 2006, the year Mr DeSantis arrived at Guantanamo, the camp was rocked by hunger strikes, violent riots and protests from prisoners over their conditions. Camp officials began to take a more aggressive tack to bring the hunger strikes to an end in the early part of the year.

In February of that year, camp authorities began to implement a more aggressive regime of dealing with hunger strikers, according to a New York Times report from the time.

That method, according to the Times, involved “strapping some of the detainees into ‘restraint chairs’ to force-feed them and isolate them from one another after finding that some were deliberately vomiting or siphoning out the liquid they had been fed.”

Mr Adayfi told The Independent that Mr DeSantis was present for a particularly brutal episode of force-feeding at the base.

“He was watching, and I was really screaming, crying,” Mr Adayfi, a Yemeni, said in a video call from his home in Belgrade. “I was bleeding and throwing up. We were in the block yard, so they were close to the fence.”

Mr DeSantis has spoken sparingly of his time at Guantanamo Bay, where he served between March 2006 and January 2007 with the US Navy, at 27-years-old, as a judge advocate general (JAG), a job which entailed providing legal representation to military personnel and ensuring the US military complied with the law. There is little mention of it in his new book and he has offered few details of what he did on the campaign trail.

But since serving at the controversial military prison, Mr DeSantis has consistently argued for it to remain open, and spoken against the release of prisoners, even though most are held for years without charge.

At a congressional hearing chaired by Mr DeSantis in 2016, the then-congressman forcefully argued for Guantanamo to remain open.

“The president’s conclusion that the detention facility should be closed is based in part on his idea that the facility is a recruiting tool for Islamic jihadists, but this represents a misunderstanding of the nature of the terrorist threats we face.,” he said. “These are not the type of people that will abandon their jihad against America and our allies simply because we close Guantanamo Bay,” he told the House of Representatives Subcommittee of National Security, part of the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform.