In the final months of the 70 s, two double albums were released that, true to the punk-torn music scene of the times, couldn’t have been more different. One of them was by a band that seemed to represent all that punk stood for: anger, anti-establishment attitude, and youth rebellion. The other was by a bunch of millionaire rock stars.

Both albums, it could be said, had apocalyptic themes. But while one was clearly about partying in the face of disaster – full of humour and good times – the other was caustic, unforgiving and nihilistic in its portrayal of post-war Britain and the education system, as well as a cynical critique of rock stardom itself. Amazingly, it was this angry double album that produced a new youth anthem, sung by kids everywhere – ‘Hey! Teacher! Leave those kids alone!’ – and immediately thrust to the No.1 spot.

So how, exactly, did millionaire rock dinosaurs Pink Floyd manage to ‘out-punk’ The Clash’s London Calling? What forces brought the kings of blissful prog rock to create their troubled, angst-ridden epic album The Wall?

It would be difficult to determine what Pink Floyd meant to the man in the street in 1979. It had been two years since their last album, Animals, released at the end of the first wave of punk. And while John Lydon famously customised a Pink Floyd t-shirt with the words ‘I hate…’ Floyd certainly weren’t short on album sales: their supporting tour had once again slogged around the stadiums and arenas of North America and Europe, playing to capacity crowds.

Yet in many ways Pink Floyd were still a cult band – because they had never recorded singles, they slipped silently in and out of rock’s consciousness with each successive album and tour, known only to a certain breed of rock fan.

While The Clash’s single London Calling stalled at No.11, Pink Floyd, who hadn’t released a single in 10 years, shot into the No.1 spot with Another Brick In The Wall Part 2, where it remained over the entire Christmas period. The accompanying video, a hastily assembled (hastily because no one thought the single would sell enough to get the band on Top Of The Pops) montage of disturbing animation and bizarre footage of a giant schoolteacher puppet, was as bewildering as it was inventive. Worryingly and weirdly, Another Brick In The Wall Part 2 also had the feel of a novelty record. What was going on with Pink Floyd?

The members of Floyd – David Gilmour, Nick Mason, Roger Waters and Richard Wright – had been slowly drifting apart with each successive album and tour since the making of 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon, and consequently the story behind The Wall is a deeply complex one, involving money, ego and a battle for creative control.

Despite their recent successes, almost everything Floyd had earned from record sales and tours to date had been wiped out, thanks to some naive investments via City brokers Norton-Warburg. Waters: “We lost a couple of million quid – nearly everything we’d made from Dark Side Of The Moon. Then we discovered the Inland Revenue might come and ask us for 83 per cent of the money we had lost. Which we didn’t have.”

Using this misfortune as a convenient lever, the ever-resourceful Waters, who had positioned himself as spokesman and chief lyricist of the band, proposed bailing them out with one of two possible album projects that he had envisaged and part written and demoed since the Animals tour: Bricks In The Wall (later known simply as The Wall) and The Pros And Cons Of Hitch-Hiking. Barely resembling what would later evolve into one of their most successful albums, Gilmour – at odds with Waters’s later view – remembered them well.

“The demos for both The Wall and Pros And Cons were unlistenable, a shitty mess,” the guitarist told me in September 1987. “[They] sounded exactly alike, you couldn’t tell them apart.”

In the end it was decided that The Wall was the better prospect. The finished album told a desperate story of isolation and fear, far more complex than anything previously tackled by Waters.

“The idea for The Wall came from 10 years of touring,” Waters explained. “Particularly the last few years in ’75 and in ’77 when we were playing to very large audiences, most of whom were only there for the beer, in big stadiums. Consequently it became rather an alienating experience doing the shows. I became very conscious of a wall between us and our audience, and so this record started out as being an expression of those feelings.”

Many of the scenes in the album also represented actual events in Waters’s or the band’s personal history. “It is partially autobiographical,” Waters confessed. “It’s a lot about my early life. I mean my father being killed [in the Second World War]. And some of it’s about Syd [Barrett] and some of it’s drawn from other experiences.”

Indeed it had taken Waters some 10 months before his demos were in a fit state to play to anyone. “I started in September [1977],” he recalled, “and it was the next July [’78] when I played it to the other guys in the band. Then we started rehearsing it and fiddled about with it, and started really recording it properly in April [1979].”

According to Gilmour, to begin with the band were “just sitting around and bickering, frankly”, but the confrontational nature of the process seemed to bring out the best in Waters, their chief songwriter. “Someone would say: ‘I don’t like that one very much,’ someone else might agree, and then Roger would look all sulky and the next day he’d come back with something brilliant. He was pretty good about that during The Wall.”

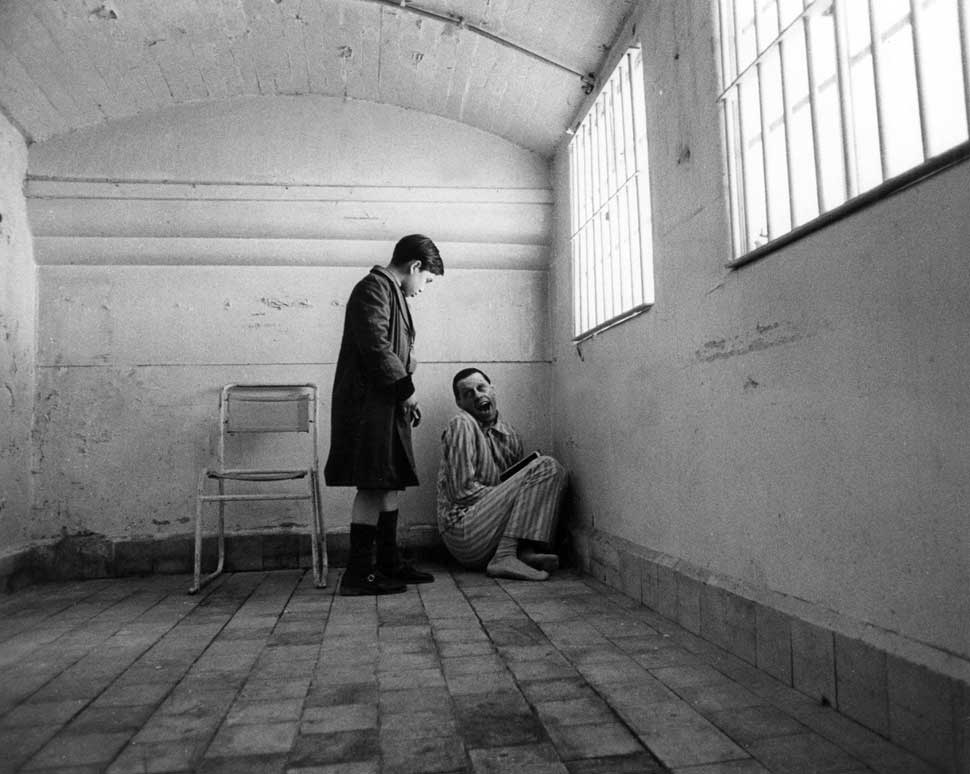

Inevitably the album is seen as partly autobiographical: Pink, the central character, played by Waters, is a successful rock star facing the break-up of his marriage while on tour (mirroring Waters’s own separation from his wife, Judy Trim, in 1975). This leads Pink to review his whole life and to begin to build a protective wall around himself, each brick representing the things that have caused him to suffer: a suffocating, overprotective mother, vicious schoolteachers, a faithless wife, stupid groupies.

Pink imagines himself elevated to the position of a fascist dictator, with the audience his obedient followers. At the story’s climax he faces up to his tormentors, and the wall finally crumbles. But as soon as this wall has fallen, another one slowly begins to rise, suggesting a perpetual cycle of imprisonment.

It was an ambitious project by any stretch of the imagination. From its inception Waters envisaged a three-pronged attack: album, tour and film. Initially it was hoped that all three would be in simultaneous production, but almost at once it became evident that the sheer magnitude of effort in the recording process alone would make that plan unfeasible.

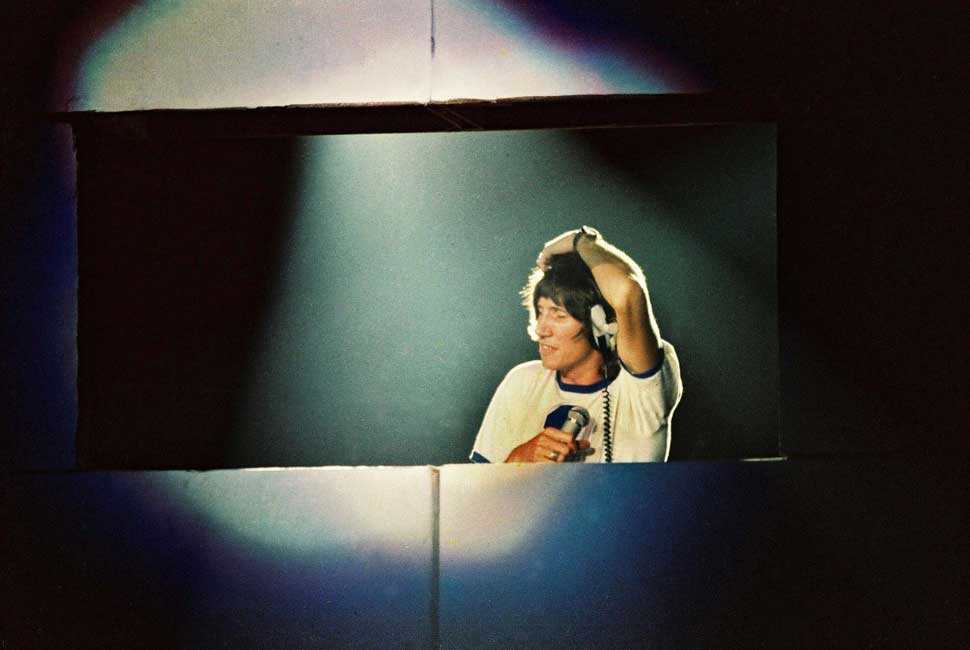

Aside from the sheer complexity of the project that lay ahead, Waters needed an outside producer to collaborate on ideas, to help co-ordinate efforts and in many cases act as arbiter between himself and Gilmour once they had started the recording process. That job went to Canadian-born producer Bob Ezrin.

Ezrin’s task was a formidable one, but he succeeded in moulding the then sorry story into a workable shape. Much later he said: “In an all-night session I rewrote the record. I used all of Roger’s elements, but I rearranged their order and put them in a different form. I wrote The Wall out in 40 pages, like a book, telling how the songs segued. It wasn’t so much rewriting as redirecting.”

“I could see that it was going to be a long and complex process, and I needed a collaborator who I could talk to about it,” Waters said. “Because there’s nobody in the band that you can talk to about any of this stuff: Dave’s just not interested, Rick was pretty closed down at that point, Nick would be happy to listen because we were pretty close at that time, but he’s more interested in his racing cars. I needed somebody like Ezrin who was musically and intellectually in a more similar place to where I was.”

Ezrin recalled that “there was an awful lot of confusion as to who was actually making this record when I first started,” complicated by the fact that a young producer, James Guthrie, was also brought in to act as co-producer/engineer. “So he brought me in, I think, as an ally to help him to manage this process through. As it turns out, my perception of my job was to be the advocate of the work itself, and that very often meant disagreeing with Roger and others and being a catalyst for them to get past whatever arguments might exist.”

Ezrin also led the band in directions they would otherwise have ignored. Another Brick… Part 2 leaned heavily on disco – a phenomenon well off Pink Floyd’s collective radar, as Gilmour recalled: “He [Ezrin] said to me: ‘Go to a couple of clubs and listen to what’s happening with disco music.’ So I forced myself out and listened to loud, four-to-the-bar bass drums and stuff. Then we went back and tried to turn one of the Another Brick In The Wall parts into one of those so it would be catchy. We did the same exercise on Run Like Hell.”

The whole recording process lasted from September ’78 until just before the release of the double album in November ’79, with initial pre-recording demos beginning in earnest at Britannia Row in London. This quickly shifted to France when the band were forced to retreat into tax exile following the Norton-Warburg crash, and with their families in tow relocated to various rented accommodations in and around Nice.

Sessions began at Superbear in Berre-des-Alpes and Studio Miravel in Le Val. Curiously, the band chose to work within civilised office hours, commencing at 10 in the morning and finishing by six in the evening. However, tensions started to run high even at this early stage. Ezrin: “There was tension between band members, even tension between the wives of the band members. Roger and I were having a particularly difficult time. During that period I went a little bit mad and really dreaded going in to face the tension. I preferred not to be there while Roger was there.”

“Most of the arguments came from artistic disagreements,” David Gilmour says. “It wasn’t total war, though there were bad vibes – certainly towards Rick, because he didn’t seem to be pulling his weight.”

If Mason and Wright’s contributions were minimal, Gilmour contributed some outstanding music for the album’s three more tuneful compositions: Young Lust, Run Like Hell and Comfortably Numb, for which he received one of only two shared writing credits on the album (the other went to Ezrin for his contribution to The Trial). Indeed Comfortably Numb features one of rock music’s most iconic guitar solos, and was a live staple in Pink Floyd’s post-Waters shows and also on Roger Waters’s own solo tours.

Offering a rare insight into their unique partnership during the making of the album, Gilmour confessed that “Roger was certainly a very good motivator and obviously a great lyricist. He was much more ruthless about musical ideas, where he’d be happy to lose something if it was for the greater good of making the whole album work. So, you know, Roger would be happy to make a lovely sounding piece of music disappear into radio sound if it was benefiting the whole piece, whereas I would tend to want to retain the beauty of that music. We often had long, bitter arguments about these things.”

Indeed what is so utterly compelling about the whole piece is the lyrical content; the depth and maturity of Waters’s songwriting is breathtaking. The summer break undoubtedly saved the Ezrin-Waters partnership. But the same could not be said of Wright who was, by his increasing lack of commitment, becoming the brunt of Waters’s hostility.

Already frustrated by Wright’s belief that he should continue to be paid a quarter-share of the production credits, when it was clear he was in no way contributing to this element at all, the crunch finally came when Waters realised that the volume of work still required to complete the record in time for delivery in October could not be met.

Via manager Steve O’Rourke, Waters requested that Wright join Ezrin a week ahead of the rest of the band in Los Angeles in order to catch up on the backlog of work. Ezrin reluctantly agreed, but Wright refused outright, telling Waters to “fuck off”, commenting that he had seen very little of his children when they were in France as he was going through a tough divorce, and that he was not prepared to go.

Waters found this unacceptable: “So I gave him an ultimatum to do as he was told and finish the record, keep your full share [of the royalties] and leave quietly afterwards, or I’d see him in court.” Wright wrestled with this ultimatum for some time, wondering if he should call Waters’s bluff. In the end he resolved to leave the band but, in a final, yet illogical, act of commitment, agreed to stay and perform on the live shows.

“It’s quite simple,” Wright explained. “There was a lot of antagonism during The Wall and he said: ‘Either you leave, or I’ll scrap everything we’ve done and there won’t be an album.’ Normally I would have told him to get lost, but at that point we had to earn the money to pay off the enormous back-taxes we owed. Anyway, Roger said that if I didn’t leave he would re-record the material. I couldn’t afford to say no, so I left.”

The album was finally released on November 30, 1979. Melody Maker’s Chris Brazier summarised it thus: “I’m not sure whether it’s brilliant or terrible, but I find it utterly compelling.” Robin Denselow, writing in the Guardian, commented: “I sympathise with those who find it too bleak to handle, but the Floyd’s new work is frighteningly strong.”

With the album done, that left the stage show and the movie. On the live shows, The Wall was Pink Floyd’s most overwhelming spectacle to date. Presented exclusively at indoor arenas in Los Angeles and New York in February and London in August 1980, and then in Dortmund in February 1981 and again in London in June, it skilfully combined every aspect of the rock theatre genre.

A wall was literally constructed from hundreds of cardboard bricks before the audience’s eyes, and by the close of the first half it spanned the entire width of the auditorium to a height of some 40 feet. The show also incorporated a circular screen on to which newly designed hideous animations by Scarfe were projected. In addition, three giant puppets made appearances at key points, representing the villains of the piece: a 25-foot-high model of the Schoolteacher, a smaller one of the Wife and an inflatable Mother.

There was even a set built into the face of the wall, depicting the motel room where Pink sits, comatose, in front of a TV showing an old war film. One of the most visually striking elements was Gilmour standing atop the wall playing his monumental guitar solo in Comfortably Numb.

What pleased Waters most about the whole production was that it was pleasantly removed from the stadium environment he so hated: “I walked all the way around the top row of seats at the back of the arena, and my heart was beating furiously and I was getting shivers up and down my spine spine. I thought it was so fantastic that people could actually see and hear something from everywhere they were seated. Because after the 1977 tour I became seriously deranged – or maybe arranged – about stadium gigs. I do think they are awful.”

With immediate sell-outs in both locations and an oversubscribed attendance it was hardly surprising that the band got offers to extend the tour. But the very idea was the opposite of everything The Wall stood for.

As Waters explained: “Larry Magid, a Philadelphia promoter, offered us a guaranteed million dollars a show plus expenses to go and do two dates at JFK stadium with The Wall. To truck straight from New York to Philadelphia. And I wouldn’t do it. I had to go through the whole story with the other members. I said: ‘You’ve all read my explanation of what The Wall is about.

"It’s three years since we did that last stadium, and I saw then that I’d never do one again. The Wall is entirely sparked off by how awful that was and how I didn’t feel that the public or the band or anyone got anything out of it that was worthwhile. And that’s why we’ve produced this show strictly for arenas where everybody does get something out of it that is worthwhile.”

Pressure was now mounting on the band to start work on the full-length movie adaptation – the third and final instalment – of The Wall, with Scarfe heading up the animation, Alan Parker as director and Waters assuming the role of producer. Filming began at Pinewood Studios in Buckinghamshire in September 1981.

The original intention had been to use concert footage in the film, but Parker was not satisfied with the results. Having decided to ditch this, he persuaded a reluctant Waters to both drop the live scenes – and to relinquish his role as Pink (it eventually went to Boomtown Rats leader Bob Geldof).

Parker’s change of plan also upset Scarfe in that his stage-show puppets would be sacrificed to the creation of an entirely new piece of work separate from the stage presentation, although about 20 minutes of his animation would be retained. It is well-documented that the three men were given to lengthy rows and walk-outs during the filming. Parker resolved the matter by forcing Waters to take a sixweek holiday so that he could work unhindered.

“In that period I was allowed to develop my vision,” Parker said, “and I really made that film with a completely free hand… And then Roger came back to it, and I had to go through the very difficult reality of having it put over to me that actually it was a collaborative effort.” Waters described it as “the most unnerving, neurotic period in my life – with the possible exception of my divorce in 1975.”

The band also re-recorded some of their works for the soundtrack, using new Michael Kamen orchestrations on Mother, Bring The Boys Back Home, and an expanded Empty Spaces. In addition, a completely new track, When The Tigers Broke Free, was introduced to act as an overture to the film. It was inspired by the death of Waters’s father on in Italy during the Second World War.

When the film opened in London it was generally seen as a powerful piece of celluloid rock music, but it did receive a few unfavourable reviews. Some of the more sensitive writers felt they had been subjected to a battering from start to finish. Daily Express correspondent Victor Davis wrote: “I got no sleep for the remainder of the night because Parker’s shocking images refused to go away.” Even Parker admitted that he “wasn’t quite prepared for the intensity of the anger that comes off the screen”.

Scarfe was particularly shocked to find that, for the filming, a notorious gang of skinheads from Tilbury had been recruited as Pink’s ‘Hammer Guard’, and now had his hammer logo tattooed on their skin. “I was slightly worried that they might be adopted by some fascist, neo-Nazi group as a symbol,” the artist confessed.

Soon after the film’s release, the band announced the release of additional material used on the soundtrack, as well as some that had been cut from both the album and the film. As Waters explained: “We were contracted to make a soundtrack album but there really wasn’t enough new material in the movie to make a record that I thought was interesting. The project then became Spare Bricks, and was meant to include some of the film music.”

However, when the album, appropriately titled The Final Cut, was eventually released, in the spring of 1983, it was very different from what had been predicted. Waters, inspired by the British Government’s military retaliation against Argentina’s invasion of the Falkland Islands, had composed and recorded new pieces of music, almost without consulting the rest of the band. It seemed that he had assumed unilateral responsibility for the direction of the band.

This was Pink Floyd’s most turbulent period, with arguments apparently raging constantly over band policy, and album quality and content. “It got to the point on The Final Cut,” said Gilmour, “that Roger didn’t want to know about anyone else submitting material. It seemed that much of what the rest of the band had cherished as a democracy was fast disappearing. There was at one time a great spirit of compromise within the group. If someone couldn’t get enough of his vision on the table to convince the rest of us, it would be dropped. The Wall album, which started off as unlistenable and turned into a great piece, was the last album with this spirit of compromise. With The Final Cut Waters became impossible to deal with.”

Waters himself admitted that it was a highly unpleasant time, but his overriding feeling was frustration at the others’ unwillingness – and this applied to Gilmour in particular – to submit to his complete control. “We were all fighting like cats and dogs,” he said. “We were finally realising – or accepting, if you like – that there was no band and had not been a band in accord for a long time. Not since 1975, when we made Wish You Were Here. Even then there were big disagreements about content and how to put the record together. I had to do it more or less single-handed, with Michael Kamen, my co-producer.”

Gilmour refused to have anything more to do with the album’s production, and was unhappy with the personal and political content for it to be anything other than a Waters solo piece. He agreed merely to perform, as required, opting for an easy life in preference to endless rows.

The power this granted Waters gratified his now tremendous ego, leaving him free to act as if his bandmates were no more than mere hired hands. Even the sleeve, under Waters’s artistic control, carried the subtitle ‘A Requiem For The Post War Dream by Roger Waters – performed by Pink Floyd’. The Final Cut, dedicated to Waters’s late father, was Pink Floyd’s worst-selling record since The Dark Side Of The Moon, just scraping the top five – a point which Gilmour has gleefully raised time and again to underline the fact that the material was exceptionally weak.

It is a curious irony that Waters’s erratic solo career has seen him take some startling U-turns in regard to his beliefs and long-held convictions about all that is bad about the corporate machine, globalisation and stadium touring.

Was the ill-fated all-star recreation of The Wall concert in Berlin 1990 a wall too far?

There are no explanations as to why Waters the solo artist subsequently chose to tour Dark Side… in its entirety (other than commercial gain) to stadiums across the world, rather than his beloved The Wall.

Was Waters finally admitting defeat? That to rail against the corporate machine, to not step in line or to play the game is a fruitless waste of energy? Maybe. After all, you can’t bang your head against the wall forever.

This feature was originally published in Classic Rock 139, in December 2009.