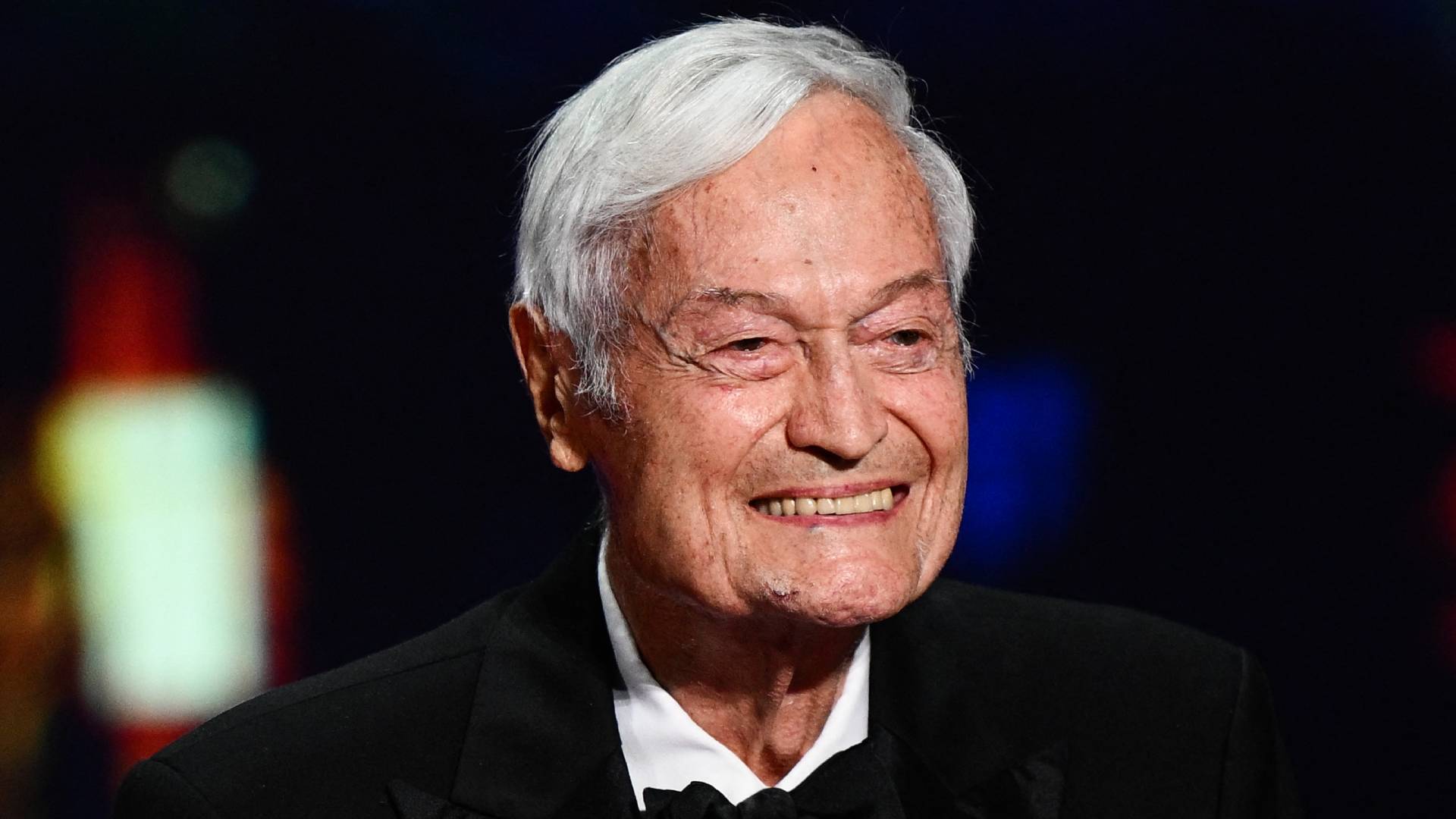

This interview originally appeared in SFX magazine issue 175 (October 2008). We spoke to Roger Corman about his heroes and inspirations for the issue.

When a young Roger Corman was shooting the likes of It Conquered the World and Attack of the Crab Monsters, he’d have been highly amused by the notion that, decades later, he’d be feted by academia. But that’s exactly what has happened to the King of the B-movie. SFX spoke to Corman at Cine Excess II, an ICA conference on cult film (typical lecture title: 'The bald and the beautiful – the performativity of Billy Zane'), where he was guest of honor.

Unlike some, Corman didn’t fix on directing as a career option at an early age. “I fell in love with horror films”, he explains, “And eventually at university I became a critic for the university newspaper. Now I had to really analyse the films that I liked. It was probably during my last year that I started thinking, ‘This is what I want to do.’”

The full extent of his “directorial training” before flinging himself in at the deep end on western Five Guns West was a day spent shooting an eight-minute short. “I had to learn on the set”, Corman explains. “I didn’t study directing, because I started as a writer, then became a writer/producer. There were two directors who did decent jobs on the first two films that I produced, but as I looked on them, I just felt, 'I can do this!’”

Things to come

“When I was a child I was very much interested in the fantastic, and I loved horror films, science fiction films. One of the first I remember was Things to Come. I’d never seen a film like that - I thought it was magnificent - and that steered me towards science fiction, building model aeroplanes and that sort of thing. I read a number of HG Wells stories – Things to Come, War of the Worlds. And I read the magazines - there was one, Astounding Science Fiction, that I subscribed to.”

John Ford and Howard Hanks

“Ford had a great feeling for the common people, particularly in the West. Great visuals, these broad shots, and then the characterisation of the hard-bitten life of the cowboy. Howard Hawks was a master of sophisticated comedy, but also capable of creating the private eye. Red River is one of the best westerns ever made. With Ford, my favourite is The Grapes of Wrath, a film somewhat away from his normal type of film, and of the westerns, probably The Searchers.”

Alfred Hitchcock

“Hitchcock was a master of the camera - it was always in the right spot, and the framing was perfect. To watch him on set was not particularly exciting, because he’d shoot the shot, flick the page of his script book, show the next sketch of a shot to the cameraman, then go to his dressing room, read the paper, come back when the shot was ready, shoot it, flip the page...

“I’ve always believed in pre-production planning. If you’re shooting a picture in a two or three week schedule - which most of my films were shot on - you don’t have time to figure out where to put the camera. You’d better have that figured out in advance, your sketches made, and come to the film knowing what you’re going to do.”

Engineering

“My father was an engineer, and when I went to university I studied engineering, feeling I would follow in his footsteps. It was three-quarters of the way through that I realised I didn’t want to be an engineer, but if I wanted to change to another major, I had to drop back a year, and I just wanted to get to the end! So I took the degree in engineering. Was that useful later on? I think a little bit, particularly in the planning and organisation. I tried to be fairly analytical and think from an engineering standpoint about the process of manufacturing a film, and then move from that to the creative aspect of ‘How will I make this film?’”

Jeff Corey

“Jeff Corey was a major influence in teaching me about acting. When I became a director, I’d learned the use of the camera and editing very quickly, but I really didn’t know anything about acting, so I enrolled in an acting class that was the one that Jack Nicholson took. Jeff was the teacher, and he was teaching the method. I felt immediately – and for the rest of my career - that there were things going in on the actors’ minds that the director does not know, so as a director I was very circumspect in giving direction. I was more comfortable simply discussing the character with the actor before the shoot began.”

The depression

“I grew up in the Depression, and most people were poor. My father was an engineer and always had a job, but did have to take a cut in salary to keep his job; there was never a question of our family starving, but it was clear that the use of money was important for us to get by. In general I financed my own films, which is unusual, and so therefore I’m aware of how much I’m spending! On the set there’s a certain amount of wasted time. There are prolonged discussions of things that don’t need discussing. Working efficiently to utilise your time is important - working rather than chatting.”

The news headlines

“The day after the news came out that the first sputnik had been put in space, I called the president of Allied Artists, went into his office first thing, and said, ‘I can put a picture about satellites in the theatres’. He said, ‘You have a story?’ I said, ‘No, but I will have a story and you can put the picture in the theatres in three months’. He said, ‘How much money do you need?’ I said, ‘$75,000’, he said yes, and it just started from there!”

The auteurs

“I’ve always liked the work of the auteurs. These are pictures where the director’s put his heart and soul into it, each one is an individual work of art.

“In the ‘70s I started distributing art films. I felt that the works of some of the directors – Fellini, Bergman, Kurosawa – were not being well distributed. I had no intention of losing money, but I thought if I could break even, that’s fine.

“The first was Ingmar Bergman’s Cries and Whispers. We opened as you normally do in New York, and followed in key cities and college towns, but then I did something people said was wild. I knew that in the fall, the drive-ins had difficulty getting pictures, so I thought, ‘Why not put Cries and Whispers into some drive-ins?’ I put it in as a drive-in in northern Louisiana because it was still a bit warmer, and the picture did average business. I actually got a letter from Bergman thanking me for bringing his film to an audience he never thought he would reach!”

Roger Corman died on May 9, aged 98. Our thoughts are with his family and friends at this time.

.png?w=600)