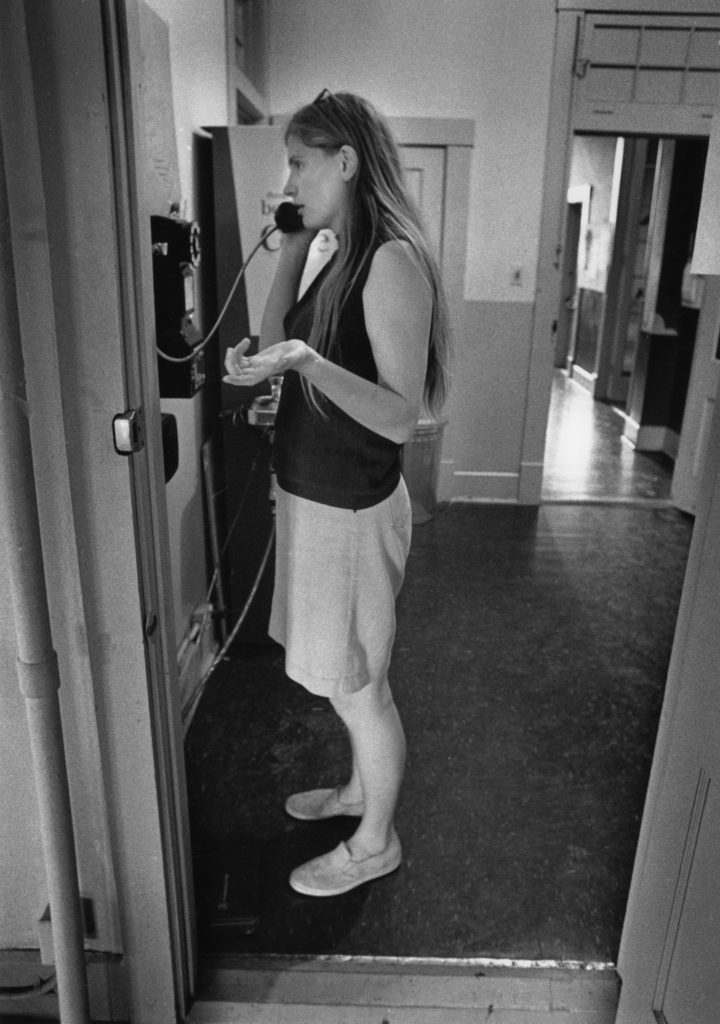

At the back of the newsroom of the Rag, Austin’s storied and raucous underground newspaper, a volunteer sat by a phone, waiting for calls from women searching for help. In hushed tones, the volunteer would tell the callers what they needed to know to get safe abortions, even though providing such information meant volunteers risked getting in trouble themselves.

It was the fall of 1969, before the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision gave women in the United States the right to an abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. The little corner office near the University of Texas campus was the Birth Control and Problem Pregnancy Information Center. Run by and for women students at UT, it was the outgrowth, in classic 1960s counterculture fashion, of consciousness-raising sessions. According to accounts and documents from Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History, the sessions led members to focus on reproductive rights, which led to the creation of the birth control information center—and much more. The students who ran it helped inspire the case that changed the history of abortion rights in this country.

One was Judy Smith, a biology student, activist, and editor at the Rag, which was at the center of what was happening on and around campus on women’s issues. The paper in those years was increasing its coverage of these topics, inspiring students across campus to speak about their experiences.

With the outpouring of support for the Rag’s articles, Smith decided to gather a group of UT women students at her house to discuss the barriers that they faced as a result of their sex. Among them was Victoria Foe, now a biology professor at the University of Washington.

In the consciousness-raising group, these women felt free to talk about the inequality and sexist treatment at UT and women’s lack of control over their reproductive lives. At the time, the student health center would not prescribe birth control for a woman unless she was married and got permission from her husband.

“It seemed like a complete no-brainer to get together information for women about what birth control was available, what was safest for women,” Foe said.

Alice Embree, another Rag editor and member of Students for a Democratic Society, said the group’s goals were much loftier than those of most activist groups: They didn’t just want to help individual women survive under unjust laws or even just to change the law. They wanted to change the underlying culture.

Embree didn’t volunteer at the call center, but she helped run the Austin Women’s Center, down the block from the Rag, to connect women to resources and activism in the city.

To make sure that the birth control information center would not send the women to a doctor who would hurt or kill them through a poorly performed abortion, Smith and Foe traveled to Piedras Negras, Mexico, across the Rio Grande from Eagle Pass, to find a doctor they felt they could trust. One doctor agreed to charge a fee of $200 for women referred to them by the Austin group. With Embree’s help, the birth control center placed ads in the Rag with the number to their information line, as seen in documents provided by the Briscoe Center.

They did this at great personal risk. Foe said she knew the police were tapping their phones because she often heard two clicks on the line instead of one. This was later confirmed in Austin Police Department documents that showed how police surveilled and prosecuted student activists at UT.

“We started to be a little bit worried because the law in Texas [was] then, as the new law in Texas is now, that people who helped a woman get an abortion are committing a felony,” Foe said. “We didn’t know whether that applied to us. We obviously weren’t doing abortions, but we were providing for women; we were helping them.”

They needed legal advice, and they didn’t have to look far. Sarah Weddington (née Ragle) was a trusted friend of Smith’s boyfriend. Weddington would become the lawyer for Norma McCorvey, or “Jane Roe,” in Roe v. Wade. Weddington died in December 2021 with the fate of the ruling hanging in the balance.

In her autobiography, A Question of Choice, Weddington wrote that she had attended some of the Austin consciousness-raising meetings and had researched the legality of the birth control information project, which is how she came to know Smith. The attorney’s boyfriend had reached out to Smith and Foe before that to help her obtain an abortion in Piedras Negras.

“I was filled with gratitude for that doctor and his assistants,” Weddington wrote. “Ron and I returned to Austin and plunged back into our usual routines. But the memories have always remained, sharp and clear.”

However, she only began looking into the legality of abortion later, after the Rag published an article that detailed the dangers of self-administered abortions. At the UT School of Law, with only five women in a student body of 120, women’s issues had not been discussed. Smith asked her one day: Could they be prosecuted and convicted as accomplices to the crime of abortion simply for referring women to those services? Although she was a year away from receiving her certification to practice, she began researching the case.

“I didn’t know the answers,” Weddington wrote. “Abortion had never been a topic in any of my law classes, and I had not been involved in any criminal cases since becoming licensed as a lawyer. … I wanted to help the project continue and succeed, so l began spending more time in the UT law library, meeting with project volunteers, and talking to law professors, law students, and other lawyers.”

Indeed, Embree said, “It wasn’t that a bunch of lawyers sat around and went, ‘Let’s do court cases X, Y, and Z.’” The Roe case came about because of grassroots organizing, she said.

Smith and Weddington kept talking about it until, one day, Smith said she was convinced that litigation was the only way to repeal abortion laws in much the same way that the Rag had won a court case that allowed the newspaper to keep publishing despite the university’s opposition. Not only did Smith believe it was the only way; she insisted that Weddington was the only lawyer who could handle the case. Not long after Weddington received her degree, she filed the suit.

“My mind whirred with all the reasons I was not the right person,” Weddington wrote in her autobiography. “We never thought we were filing what would become the Supreme Court case.”

While the case was being formulated, Foe continued her efforts to get the Texas Legislature to repeal its abortion law. As an assistant to two state senators, she organized legislative hearings to take testimony from women and about women who had tried to perform self-induced abortions with harmful and at times deadly results.

“We had … nurses who testified about the horrible, bungled abortions that come to the emergency room, of women desperate, so desperate that they put crochet needles and things up themselves to try to break the placenta waters and abort themselves,” Foe said. “I mean, it’s just horrible the things people would do. And they’re just absolutely desperate not to have a child. One of the women who testified … had taken a book and just beat herself until she aborted.”

She said that the hearings drew extensive press coverage, but senators did not move forward with legislation because they had decided to let the courts decide the law.

Embree said the need for abortions will never stop, and neither will the fight for abortion rights. Despite the current dire situation of abortion rights, she said that the Texas organizations working on the problem now are much more advanced in the sense of being more inclusive and cognizant of how abortion laws affect different groups. That shows the difference grassroots activism can make and has already made, she said.

“It’s not six grad students; it’s much more diverse leadership,” Embree said. “It’s much more intentional about serving low-income and diverse communities and being very conscious of what are all the barriers and many privileges that can affect access” to abortion services.

Shannon Morris is an organizer with Rise Up 4 Abortion Rights, which is organizing protests across the nation. A native Texan, she said she had an abortion when she was a 20-year-old in college.

“I know that I would not have been able to finish school if I had not had my abortion,” Morris said. “I remember thanking the doctors profusely for allowing me to have a future. It is terrifying what is happening. They are taking away our rights, our futures.”

Morris said she is grateful for what the activists of the past gave her but feels like history is on a backward slide. The rights that many once took for granted are now increasingly under threat.

“We shouldn’t have to be doing this again,” she said. “I am starting to feel like this is just the beginning of rights that they want to take away from us: It’s abortion now, it’s contraception tomorrow, and gay marriage. We are just going to have to keep fighting for our basic human rights.”