It’s almost impossible to take your car for a drive without seeing some of the millions of animals that are killed on roads each year.

Such deaths, commonly referred to by researchers as roadkill, negatively affect wildlife populations. But exactly how it does so remains unclear. Raw roadkill counts are not enough to determine how roadkill can disrupt a population’s survival.

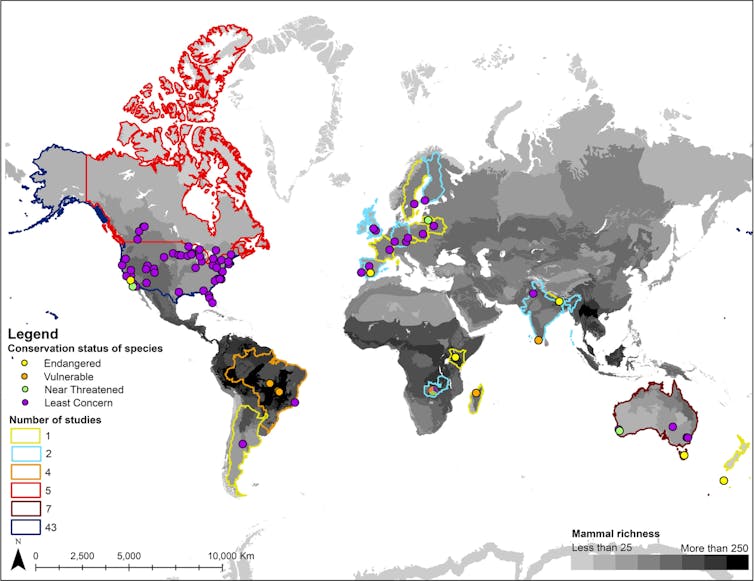

In a recent study, my colleagues and I gathered published data on 150 mammal populations from 69 species around the world. We then compared mammal deaths on roads to key biological parameters including population size to determine the effect of roadkill on different animal species.

We found that roadkill was the most common cause of death in almost a third (28%) of the populations studied – ahead of causes like disease and hunting. In some animal populations, up to 80% of all deaths were due to collisions with vehicles.

Across the species studied, roadkill affected the structure of populations, reproduction and even a population’s survival. In some species, particularly those that are rare or listed as threatened with extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, even low rates of roadkill can be damaging. If road deaths force overall death rates above rates of reproduction, then populations may struggle to replace the individuals killed on roads.

Which species is most at risk?

The species most vulnerable to vehicle collisions included the endangered Iberian lynx, Tasmanian devils, African wild dogs, giant anteaters and the near-threatened San Clemente island fox.

Vehicle collisions halved the growth rate in giant anteater populations in Cerrado, Brazil. At current roadkill rates, some giant anteater populations may become extinct in about ten years. Giant anteater populations are particularly sensitive to road deaths as the species live for a long time and are slow to reproduce.

Surprisingly, we found that the impacts of roadkill vary for different populations of the same species. The proportion of beech martens that were killed on roads each year ranged from 1.11% of their population to 33%. While there was a 20-fold difference in the contribution of road deaths to total deaths across elk populations in North America.

These differences probably arise because populations are subject to multiple threats simultaneously. For example, many deer species, including elk, are hunted at varying levels throughout the year. The degree to which a population is hunted can influence how it is affected by additional road deaths.

But roadkill figures cannot be taken at face value. We found that a large amount of roadkill does not necessarily cause wild animal populations to decline.

High rates of roadkill sometimes highlight that a population is large and healthy – more individuals simply leads to a greater risk of collision. If a population has high reproductive rates, it can maintain stable population numbers despite vehicle collisions.

In the US state of Michigan, 12.5% of an American marten population died due to vehicle collisions between 2001 and 2005. But the researchers considered this death rate to be sustainable as their population increased at a rate of 16% each year for the following three years.

Vulnerable females

However, our study revealed that road deaths for female animals is more common and severe than identified by previous research. This means that for some populations, females are killed on roads more frequently than expected based on their numbers in the surrounding population. This is a concern because females often have the main role in rearing young so tend to be more important for population survival than males.

Female road mortality also has several indirect effects.

Another study, from 2011, found that when a mother San Clemente island fox (a species found exclusively on the Californian Channel Islands) was killed by a vehicle, its young starved to death. And following the death of puma mothers on the road, research has also found that puma cubs were killed by unrelated adult males. The killing of young animals of the same species – known as infanticide – is more common in mammal species where just a few males compete to reproduce with several females.

What’s next?

Road networks are increasing and remain a pressing issue for conservation. In the UK alone, traffic volume is expected to increase by up to 51% by 2050.

Measuring the effect of roadkill in the way we have will help design conservation work in the future that identifies and targets the most at-risk populations. This is particularly important in countries that host threatened species and the world’s last remaining wilderness areas.

Maintaining “roadless” habitats in areas that are home to species threatened by roadkill - an approach known as roadless area conservation - is one option. In the US, over 58 million acres are designated as roadless areas across 38 states.

When driving, the sight of animals laying dead on the road is a familiar one. Our study suggests that these deaths affect all species differently. By understanding which animal populations are most threatened by roadkill, we can limit its impact.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 10,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.

Lauren Moore receives funding from Nottingham Trent University and People's Trust for Endangered Species.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.