A Southland community group stares down one of NZ’s biggest companies

Meridian Energy is valued at $14.4 billion, but it hasn’t had its own way over the country’s largest hydro power station.

In 2018, Southland’s regional council notified its proposed water and land plan which changed the activity status of the Manapōuri power scheme from discretionary to controlled – something Meridian had pushed for.

(This was done by commissioners, who went against the advice of council planning officers.)

READ MORE: * Power discord: The battle over NZ’s biggest water take * Flipping a $4b coin: Flooding Lake Onslow wetlands v restoring great Waiau River

Having controlled status means when the scheme’s consents are renewed – as they need to be by 2031 – the council’s considerations are narrowed if certain pre-conditions are met.

This aspect of the plan was appealed to the Environment Court by dairy company Aratiatia Livestock Ltd, which farms 600 hectares in Western Southland. Many other parties joined the appeal, including Meridian, conservation group Forest & Bird, and Ngā Rūnanga.

In evidence to the court, opponents said the power scheme was causing devastating environmental effects on the river and the creatures within it.

Last month, the Environment Court confirmed a settlement between the parties that changed Manapōuri’s status back to discretionary.

“It’s an extraordinary outcome for a tiny community against the might of the third-largest company in New Zealand,” says Paul Marshall, a former Reserve Bank economist who’s a director of Aratiatia Livestock, and co-founder of the Waiau Rivercare Group.

“But more, it’s a massive win for our awa.”

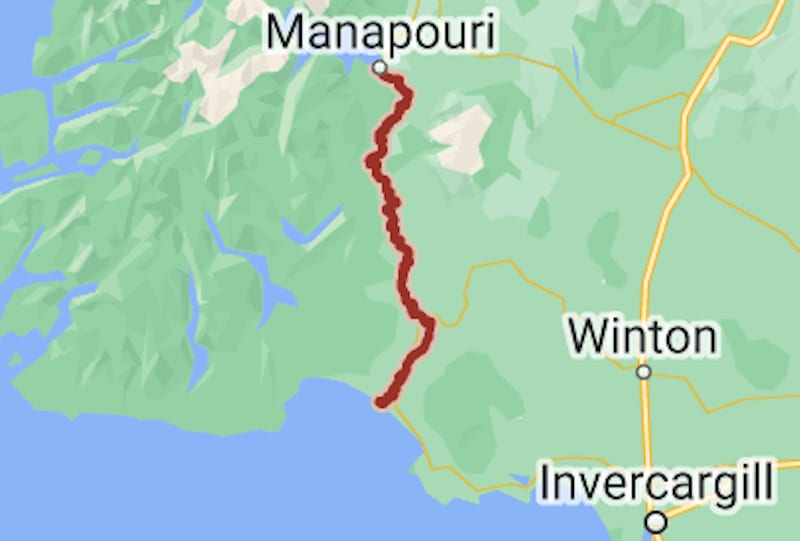

The Waiau was New Zealand’s second-largest river, in terms of discharge, with up to 95 percent of the river’s former flow allocated to the power station.

Jacob Smyth, resource management officer of Fish & Game’s Southland regional office, says there are national benefits from the power scheme.

“But there are also very significant localised effects, which are difficult to mitigate, effectively, without more water in that river. And it’s just a question of how that is delivered, in shape and form.”

He says there should be consideration of ecological flows, minimum flows, and flushing flows to deal with issues such as didymo, which has had a severe impact on the river’s trout fishery.

Environment Southland general manager of policy and government reform Lucy Hicks says discretionary activity status for Meridian’s consents means all environmental effects can be considered, including effects on the Waiau River.

“The activity status will be reviewed again as part of Plan Change Tuatahi, which will introduce limits and environmental flows for the Waiau River, as required by the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management.”

Environment Southland’s website says the plan change “will set limits, targets and methods … that will help achieve hauora, a state of healthy resilience, for waterbodies”.

Claire Jordan, Marshall’s daughter, was Aratiatia’s planner and is a committee member of the Waiau Rivercare Group. She says of the court settlement: “It gives Environment Southland, as the regulator, some strength. It gives them the opportunity to be brave and to stand by this community, and this river.”

There’s now the ability to put more water back in the river, she says, which, under controlled status, probably wouldn’t have happened.

“It makes it really difficult for Meridian, to get to argue to have more.”

(Meridian, which is 51 percent owned by the Government, provided an unattributed statement, which can be found at the bottom of the story.)

Other additions to the water and land plan because of the court settlement were: ensuring the main activities of the power scheme weren’t exempt from water quality standard considerations; and decision-makers considering the scheme’s consent renewals having to consider the river’s mauri (life force) and ecosystem health.

Meridian had wanted a broad statement inserted into the plan’s renewable energy policy for the council to consider other polluting or water-extracting activities, even below the scheme’s control gates.

“We managed to argue that that broad consideration of the Manapōuri power scheme was unnecessary,” Jordan says, “and that it needed to be narrowed to the particular activities that Meridian could actually argue did have the potential to have a genuine impact.”

A concession made to Meridian was a statement the activity status rule would be re-considered under Plan Change Tuatahi.

That would have happened anyway, Jordan says.

What are the realistic prospects of greater protection, or increased flows?

Absent any regulatory changes from local government, or high-level changes from the Government, Jordan says that will depend on Plan Change Tuatahi.

Then it’ll be up to how effectively the community argues for greater protections – alongside the importance of renewable energy.

“Clearly, it’s very important, right? But not at any cost.”

Farming won’t get a free pass – she expects the plan change to restrict polluting land uses.

Marshall, of Aratiatia, says this court settlement win for the Waiau depended on pro bono support from its legal team, Douglas Allen at Ellis Gould, in Auckland, and Riki Donnelly at Preston Russell, in Invercargill, and from its planner, Jordan.

“We also acknowledge the support we have from Fish & Game, Federated Farmers Southland, Forest & Bird and the technical evidence from the Ōraka Aparima Rūnaka witnesses.

“This was a win for our whole community.”

Jordan says the court settlement is a victory for small communities everywhere “who are faced with being browbeaten by a large corporate entity”.

“You can actually make a difference through the resource management process. It is possible.”

Unattributed statements

A Meridian spokesperson said: “We are satisfied with these consent orders and pleased the group of stakeholders, which included Meridian, could agree on a pragmatic interim solution. The consent orders present no issues for us and pave the way for all voices to be heard when public consultation takes place on Plan Change Tuatahi, which will go before an independent hearing panel in 2025.”

Forest & Bird also sent an unattributed statement: “We are grateful all parties were able to reach the right outcome by consent. Discretionary status will enable the council to consider future ecological unknowns, for example, biosecurity incursions or other adverse environmental effects resulting from climate change, and stricter conditions around the reconsenting application can be imposed. Forest & Bird is happy with the result and will be keeping a close eye on the upcoming Plan Change Tuatahi where the same matters in relation to the [power scheme] are likely arise again.”