Rishi Sunak’s resignation from government alongside Sajid Javid on 5 July triggered a landslide that saw more than 50 Conservative ministers follow suit over a chaotic 40-hour period that finally brought an end to Boris Johnson’s scandal-plagued premiership.

With the prime minister on the way out, the former chancellor, 42, initially found himself leading the parliamentary leg of the contest to replace him but has since fallen behind foreign secretary Liz Truss in what is now a straight two-horse race.

Mr Sunak had moved quickly to set up a campaign headquarters in a Westminster hotel immiediately after he stepped down and quickly fired out a slick promotional video, hoping to conjure warm memories of his generosity when Covid-19 first slammed Britain into lockdown in the spring of 2020.

That period, in which he became the fresh face of the £69bn furlough scheme keeping citizens in work and was even dubbed “Dishy Rishi”, was a happy one for Mr Sunak in which he was cheered on as a free-spending chancellor known for posing behind his laptop in a hoodie and ferrying plates around Wagamama to promote his Eat Out to Help Out initiative.

But this year has proved to be rather more of a rollercoaster ride for Mr Sunak, who began 2022 as the man most likely to succeed Mr Johnson – then mired in Partygate – before being brought low by controversy over his family’s tax arrangements, only to then turn his fortunes around once again this month.

As he seeks the keys to No 10, the challenge for Mr Sunak will be to convince his peers that he is the ideal man to revive an ailing economy that he himself has been at the helm of for two-and-a-half-years and to do so without the tax cuts they demand but which he has dismissed as “fairytale” politics.

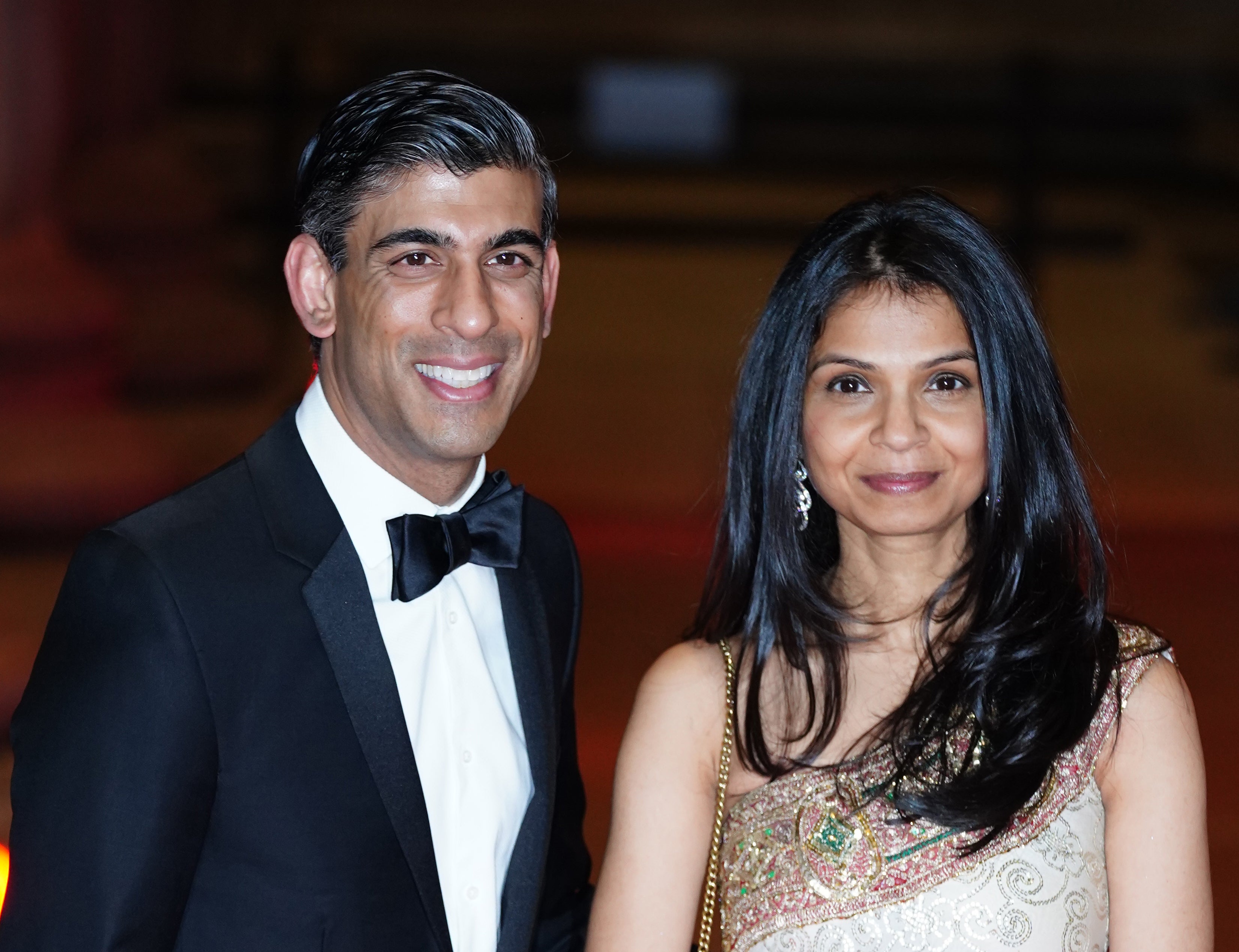

Should he win, he will also eventually have to convince the electorate that his being one of the richest MPs in Westminster, thanks to his marriage to Indian billionaire’s daughter Akshata Murthy, need not be an obstacle to understanding the realities of poverty in Britain today and delivering the help they need to make ends meet in the face of rising bills and swiftly declining living standards as inflation bites.

Mr Sunak was born in Southampton on 12 May 1980, his parents Yashvir and Usha Sunak a GP and pharmacist respectively, the couple originally from East Africa with roots in Punjab, India.

The eldest of three children, Mr Sunak attended the prestigious Stroud School in Hampshire and Winchester College, where he was head boy and edited the school newspaper, waiting tables in a curry house during the school holidays to boost his coffers.

Slightly embarrassingly in hindsight, the family appeared in a BBC documentary in 2001 entitled Middle Classes: Their Rise and Sprawl, a clip of which recently resurfaced online and went viral in which the future chancellor can be seen declaring that he has working class friends, before retracting the statement.

From there, he studied politics, philosophy and economics at Lincoln College, Oxford, and, according to Tatler, talked about himself as a future Conservative prime minister even then.

He then worked as an analyst at Goldman Sachs before joining a series of hedge funds, marrying Ms Murthy, daughter of “India’s Steve Jobs”, NR Narayana Murthy, in August 2009 and finally entering politics by becoming the MP for Richmond in the Yorkshire Dales following the 2015 general election, succeeding William Hague.

Serving as parliamentary under-secretary for local government and then chief secretary to the Treasury, he was appointed chancellor by Mr Johnson on 13 February 2020, a matter of weeks before Covid first arrived on these shores.

Popular for much of the pandemic, even Mr Sunak could not remain entirely untainted by Partygate, which first erupted, like the Omicron variant, in late 2021.

Wave after wave of damaging stories about rule-breaking wine fridge booze-ups at Downing Street while the country was in lockdown continuously rocked the Johnson premiership throughout December and January, with only the Omicron scare and Christmas providing respite.

The scandal whipped up real anger among the British public, already incensed by Dominic Cummings’ illicit road trip to Barnard Castle, who had been imprisoned in their own homes, frightened for the future, unable to go to work, see their friends and relatives or even say goodbye to those they lost to the virus.

Resentment festered over the PM’s apparent blithe indifference for the very people he had presumed to represent ever since they had handed him a landslide election victory two years earlier and whose faith he had repaid with a “one rule for them, another for us” approach to governance.

Mr Johnson struck an increasingly desperate and discredited figure in January as Whitehall mandarin Sue Gray gathered what looked like damning evidence against him and turned much of it over to London’s Metropolitan Police, compelling officers to launch an investigation of their own, as seething backbenchers handed in their letters of no confidence to Sir Graham Brady’s 1922 Committee in droves.

Meanwhile, over in No 11, Mr Sunak shrewdly kept his distance until he was eventually forced to concede that he had attended a Cabinet Room birthday bash for Mr Johnson.

He apologised for doing so by saying: “I can appreciate people’s frustration. And I think it’s now the job of all of us in government and all politicians to restore people’s trust.”

During his boss’s darkest day – a particularly savage Prime Minister’s Questions in the House of Commons on 12 January – Mr Sunak absented himself in Devon and only that evening tweeted a rather half-hearted message of support, saying only that Mr Johnson had been “right to apologise” and calling for “patience”.

By 23 January, he was being accused of sounding out potential backers for a leadership challenge among Leicestershire’s “Pork Pie Plotters”.

Six days later, there were claims he had described Partygate as “unsurvivable” for Mr Johnson while his aides, including “boy genius” adviser Cass Horowitz, had reportedly “built a draft version of a campaign website, taking inspiration from his weekly No 11 newsletter, and developed a marketing strategy” in anticipation of an imminent leadership bid.

By 3 February, Mr Sunak was openly refusing to rule out running for the top job in an interview with the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg and distancing himself from the PM’s unjust smear against Sir Keir Starmer over the failure of the Crown Prosecution Service to go after notorious paedophile Jimmy Savile during his tenure as director of public prosecutions.

But before Partygate could reach the crescendo that looked inevitable, Russian president Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February, the very same day that Mr Johnson ended the last of the social restrictions imposed in England to contain the coronavirus.

The pandemic was largely swept from the news agenda as the world watched events unfolding in Eastern Europe with horror, quickly rallying behind the courageous resistance put up by the Ukrainian people.

Leading the international condemnation of Moscow, Mr Johnson was unexpectedly able to rehabilitate his image by feeding defensive weapons and aid to Ukraine and even visiting Kyiv to tour the city centre in person in a show of solidarity with president Volodymyr Zelensky.

Mr Sunak, meanwhile, was left languishing at home and endured a torrid time of it, delivering the bad news about a worsening cost of living crisis, which has seen inflation climb to a 40-year high and household energy bills rocket by 54 per cent.

His widely unpopular Spring Statement on 23 March saw him fail to add to the £350-a-year aid package he had already announced to help families tackle the booming cost of heating their homes and fail to ditch an imminent rise in National Insurance.

Despite a crowd-pleasing cut in fuel duty, a YouGov poll concluded that 69 per cent of Britons believed the chancellor had not done enough to help working people out of financial hardship.

The days that followed saw Mr Sunak face media scrutiny the likes of which he had never previously known, resulting in a succession of gaffes that exposed his apparent inexperience and naivety.

He tried in vain to defend the proposition that he, of all people, was telling low-income families they would simply have to tighten their belts and go without.

A phone-in on LBC landed him in an uncomfortable encounter with a single mother who said she was unable to keep her radiators on and worried for her children.

A question about the price of bread in an interview with the BBC drew the response, “We have all different breads in my house”, and a publicity stunt at a Sainsbury’s petrol station saw him forced to borrow a staff member’s Kia Rio and struggle to pay at the till with his contactless card, as though he had never before had to buy a can of Coke and a Twirl in his life.

Fashion columnists had already noticed the £795 Reiss shearling jacket Mr Sunak wore on an ice skating trip to the Natural History Museum with his daughter in the New Year and were now raising eyebrows over his £335 trainers as the perception grew that the chancellor was in no position to understand the very real concerns of the electorate.

A revelation that he and Ms Murty had made a £100,000 donation to Winchester College, his old alma mater, hardly helped matters.

Nor did The Independent’s subsequent story that Ms Murty, believed to hold a £690m stake in her father’s giant IT services company Infosys, had saved millions of pounds in tax on her earnings thanks to her non-dom status, an entirely legal strategy but not a good look in the current dire fiscal climate.

Already facing awkward questions about Infosys’s business ties to Russia, Ms Murty announced on 8 April that she would now pay tax after all but it was too late to stem the criticism of her partner.

A further story about Mr Sunak still holding a US green card – the family have a second home in sunny California – while working for the British government, provoked further demands from Sir Keir that he “come clean” about his personal affairs.

The strain beginning to show, the chancellor complained in an interview with The Sun that he believed the opposition was responsible for the leaks against his wife (the party has suggested he “look a little closer to home”) and moved his family out of Downing Street.

He wrote to Mr Johnson referring himself to Lord Geidt, then the independent adviser on ministers’ interests, asking for an investigation to be carried out into his private finances in order to establish that he was guilty of no wrongdoing.

Making matters worse, he – along with Mr Johnson and the latter’s wife, Carrie Johnson – was given a £50 fixed-penalty notice by Met Police on 12 April for attending the rule-breaking birthday bash.

Despite announcing further measures to help families through the ever-worsening economic crisis, Mr Sunak’s popularity dwindled while Cabinet colleagues Ms Truss and Ben Wallace drew plaudits for their support for Ukraine and Mr Johnson soldiered on, weathering one scandal after another.

The Chris Pincher affair finally saw the Conservative Party’s patience run dry, leading to the operatic events of early July.

Mr Sunak’s decisiveness over that issue has helped his cause immeasurably and he has the backing of such influential backers as Oliver Dowden, Grant Shapps and Dominic Raab but whether he can convince the wider party of his merits remains to be seen.

In the final two of the leadership battle, the former chancellor finds himself preaching fiscal responsibility and pragmaticism against Ms Truss’s gung-ho tax cut promises.

As the duo clash over which of them is the true Thatcherite and the most committed Brexiteer in a race that threatens to turn ever more toxic and personal at a time when Britain faces numerous urgent crises, the road to 5 September and Downing Street threatens to be a long and winding one.