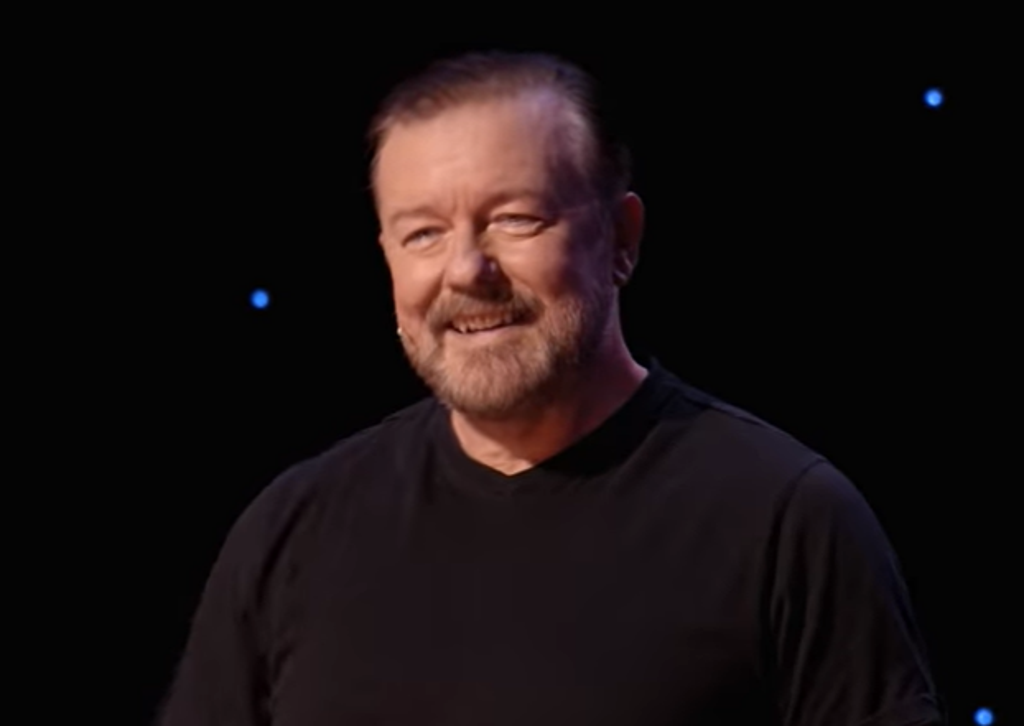

The fact that Ricky Gervais is a popular stand-up comedian, who still sells out tours and is employed to do expensive televised specials, will baffle some people. He is the closest thing we have – barring all yeast-based savoury food spreads – to literal Marmite. Ever since he burst into the British comedy mainstream, way back in 2001 when the first episode of The Office aired, he has polarised opinions – but, if the extended riff on “eskimos” in this, his new Netflix special, SuperNature, is anything to go by, he is more than happy living at the poles.

Asked (by himself, this is stand-up after all) why the show is called SuperNature, Gervais responds that he will be dealing with the supernatural and his belief in the non-existence thereof. “You seen all the ghost hunter shows?” he asks his audience, lampooning the genre in a protracted comparison with the output of David Attenborough (which he prefers). Aw, you might say, this all sounds quite sweet. And, in a way, it is. But it comes only after a lengthy opening segment that has nothing to do with the supernatural and everything to do with the terror of identity politics (“The one thing you mustn’t joke about is identity politics,” apparently). All the relevant buzzwords (“cancelled”, “woke comedy”, “virtue signalling”) are cycled through in the first 15 minutes, and when his jokes about the spirit world arrive they are a welcome, but brief, respite.

The problem with SuperNature, as with much comedy these days, progressive or irreverent, is that it finds itself sucked into the self-referential death spiral of the culture wars. Gervais has always been a master of this. From The Office to his stand-up, he revels in acknowledging the “you can’t say that anymore” element of taboo comedy. “That was irony,” he disclaims early on. “There’s gonna be a bit of that throughout the show.” And I suppose there is: whether it’s talking about sexual assault, paedophilia, disability, obesity or whatever, we are intended to imbue the jokes with the patina of chuckle-excusing irony. As is all too frequent these days, the longest riff is reserved for the humiliation of trans people. “Full disclosure,” he reveals towards the end of the show, “in real life, of course I support trans rights.” At this point there are a few stray cheers from the naïve few in the audience who think the irony is real, but that’s nothing compared to the roar of laughter and applause when the punchline – a crass joke about gender affirmation surgery – arrives.

Whatever. Being offended by the content is a victory for Gervais, who is more comfortable in the composition of quips that rely on a cheap shock factor than any emotional or creative truth. And despite the vapid laziness of most of the undertaking, there are a few things to enjoy about SuperNature. Gervais’s brand of outspoken atheism – very popular in the mid-Noughties under folk like Christopher Hitchens and Sam Harris – has gone so totally out of fashion that it now has an almost charming quaintness (and is preferable to jokes about watching Louis CK wank or not being hot enough for “paedo teachers”). In the moments where the set slips the bonds of contemporary social preoccupations, Gervais seems gleefully nostalgic for a time when racist jokes were admissible under the progressive veneer of being anti-organised religion.

There are a few sweeter jokes (of the egg and milk producing duck-billed platypus, Gervais notes that “it could make its own custard”) but that’s not what the braying mob at this special wants. Jokes about the 20th-century Swiss behavioural psychologist Jean Piaget land, tellingly, less strongly than jokes about punching disabled toddlers. Lacking the courage to write gags about things he actually believes, Gervais continuously inoculates himself against sincerity (“This is so childish and misinformed, it hurts,” he says, giggling, before telling a long, rambling and, you guessed it, anti-trans joke). But the audience doesn’t have the luxury of imposing that ironic distance. They hoot and holler along with all the bigotry, seeming to enjoy it more the closer it gets to the edge, the more buttons it pushes. “Please welcome to the stage a man who really doesn’t need to do this,” Gervais’s disembodied voice announces as the title comes up. He might not need to do it, but we definitely don’t need to watch it.