Nobody rushed to disagree with Julian Gollop when, in 2017, he declared that XCOM had become its own genre. By that time, after all, Ubisoft and Nintendo had backed the XCOM blueprint, while Gollop himself had raised $760,000 to develop his own spiritual successor. Months later, Xbox would announce Gears Tactics. Yet Gollop, a mild-mannered Brit who had seen his fair share of failure, was no egotist. The designer placed credit firmly with Firaxis, the studio which had revised his formula for the modern age. Gollop himself was happy to follow in Firaxis' slipstream, incorporating the friendlier touches of the rebooted XCOM into his own work. "I am really excited for the future,” he wrote in a PC Gamer column. "I am not alone any more."

Thirty years ago, it was a different story. Not only was XCOM not a genre, but game genres were amorphous, lacking the focus brought by a budding PC platform and the rise of PlayStation. Games were unidentified objects, and few were stranger than the project that mixed board game battlefield simulation with Civilization's global sweep.

Stealth and strategy

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features, interviews, and more delivered right to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge.

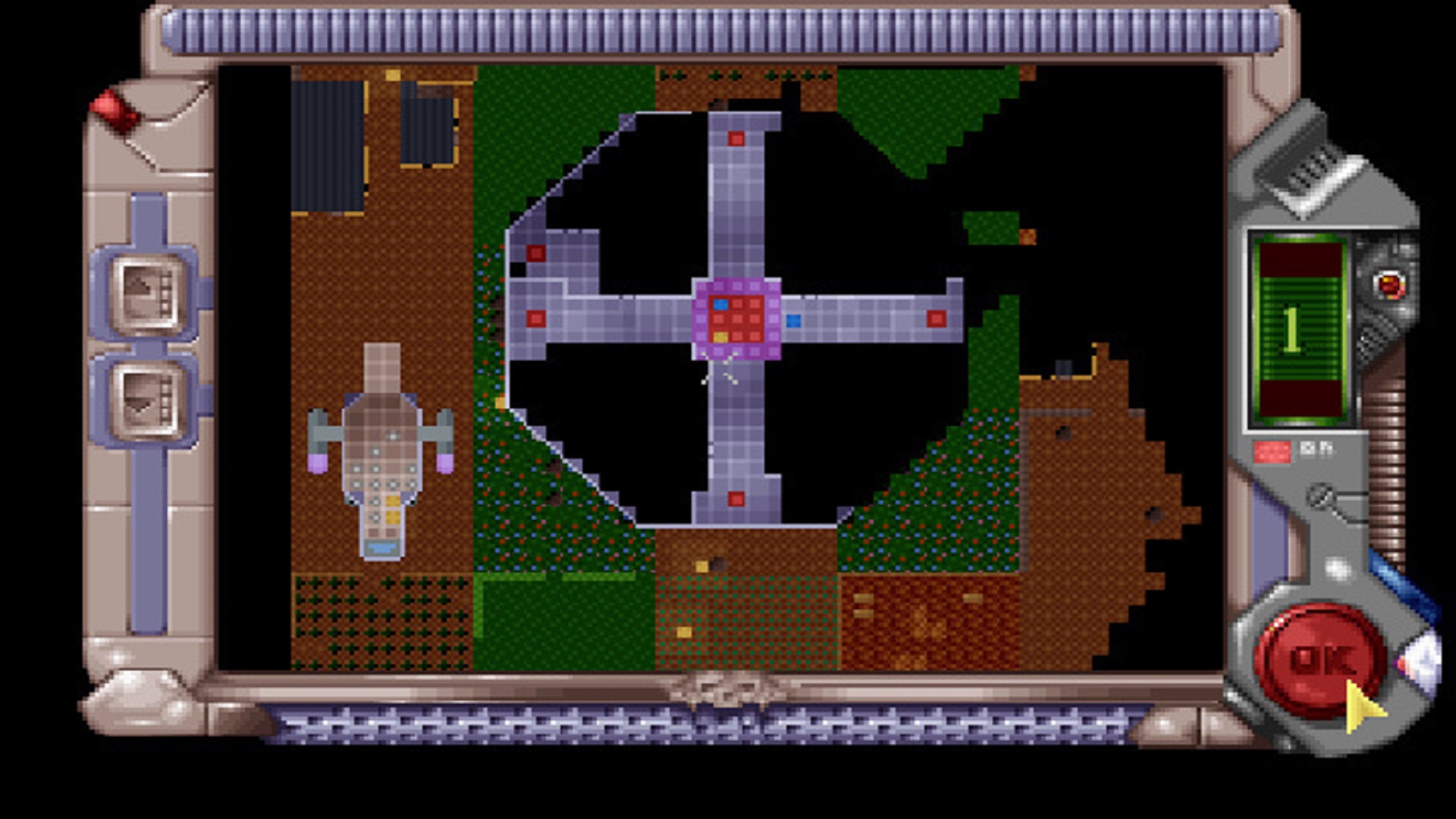

Had the stealth genre been formalised by this time, perhaps it might have been easiest to classify X-Com that way. It certainly fits the profile: a game about scanning an opaque environment for information that can give you an advantage. That's true on the battlefield, where every grid in the fog of war holds the potential to contain a Sectoid or Muton until a soldier casts an eye over it. And it's just as true on the Geoscape, the global view of your war against an alien force. There, UFOs only become visible if you've set up a radar system in their vicinity, while the unknown enemy only becomes familiar through slow and determined dissection and interrogation – a process that allows you to learn what to expect, and how to counter it. Fail to gather enough information, at every level of the game, and your initial underdog status will ensure that you don't get far.

In terms of stealth games, X-Com is more Thief than Metal Gear: swathed in shadow, it hides your opponents just as it does you. If all is quiet, that only indicates you've missed something, and are likely to trip over it later. During the enemy movement phase, Gollop draws a curtain over the action, captioned with the ominous ‘HIDDEN MOVEMENT'. Occasionally you'll be granted a glimpse of a slithering Snakeman, or hear the sound of a pneumatic door sliding open, each detail a clue as to where the next attack might come from. But you'll never catch them all.

In its reboot, Firaxis was kinder about all this. On the battlefield, the developer grouped enemies in clusters, reducing the chance you'd be caught off guard by a straggler, even as your opponents scattered like pigeons. And on the Geoscape, it periodically presented you with a platter of alien operations to interrupt. You could only tackle one – the kind of painful, pyrrhic choice that sold XCOM to a broader public – but at least you knew your options. In Gollop's 1994 original, it's all too easy to watch the realtime clock tick by without a clear sense of what's going on outside your sensors. In that sense, it's far closer to the gnawing anxiety of non-gaming life, where decisions are often made passively, and you're left unaware of opportunities missed until they've passed into history.

This callous willingness to let the player sleepwalk into disaster may not appeal to more recent fans of the XCOM genre, which now has handholds to save you from wasting tens of hours on doomed campaigns. Even as fans of the original, we have to admit to a certain amount of masochism. We've come to think of the techniques we've developed for survival in X-Com as turn-based coping strategies. The smoke grenade tossed from the landing craft before any soldier dares set foot on land; the unmanned hovercraft sent to scout territory and absorb enemy fire; the single soldier left behind on the plane so that, in the event of a squad wipe, we won't lose the deposit on the rental. All tics picked up after traumatic ‘never again' scenarios.

High stakes

Then there's our tumultuous love affair with the Alien-esque motion scanner. It's a simple bit of kit which tracks nearby movements, Battleship-style, on a blank grid. It might, for instance, highlight a blip eight squares north and six squares east. It's then up to us to cross-reference that information with the battlefield, and decide whether the blip is alien, civilian, or irrelevant noise from two floors above. Misreading is all too easy, and leads to misplaced confidence. But getting it right – which in this case means firing straight through a grocery-shop wall to take a Snakeman by surprise – is a real X-Com moment, when wits, preparation and luck come together in our favour.

Yet no amount of prep and experience can keep a squad safe in perpetuity. Mind control remains a peril for the entire length of a campaign, combatable only with a vicious mental vetting process. Some veterans recommend disarming troops in advance and walking them out into the fields to test their susceptibility to Sectoid influence. "You should not be too queasy about shooting any of your soldiers which are under alien control," reassures UFOpaedia. "You will probably have to sack them anyway for being psi-weaklings."

Even away from the brainwashers, the wild variations in X-Com's RNG can do for the most seasoned soldiers. Men and women in power armour are regularly insta-killed when subjected to the green glow of plasma fire, damage modifiers be damned. Fortunately, X-Com is flexible in its tech tree, and the bane of your existence can swiftly become your squad's greatest asset. Present a plasma rifle to your science team early on and, with enough funding, you can bypass the business of experimenting with ballistic and laser weapons entirely, suddenly equalising damage on the battlefield. Though there's always a trade-off. For many months in the war for Earth, we got by with glass-cannon rookies until, eventually, the success of our assaults afforded us the luxury of armour. The imbalance continued in the air, where rinky-dink planes built for buzzing Cold War rivals were fitted with plasma beams to take down multi-storey UFOs.

These quirks in your setup feel personally expressive, and reinforce the fantasy of running a scrappy startup that can only bring about victory by making bold moves. It's a stark contrast to strategy genre fare that demands you follow a linear path to dominance – and, in fact, X-Com only becomes more like running a disruptive business in the late game. By that point, your dependence on the Council Of Nations for cash feels increasingly risky. With a growing staff of soldiers, scientists and engineers, your running costs are a concern. And while each country is diverting ever-larger amounts per month to the war effort, that flow can be cut off without warning when a nation throws in the towel and signs a treaty with the aliens. Worst of all, if you're repeatedly short at the end of the month, the Council is liable to shut down the X-Com project, finishing your campaign prematurely.

Given those high stakes, it makes sense to diversify your income streams with a little arms dealing. We couldn't tell you how Fusion Ball Launchers are used in battle, or in what disputes our buyers are deploying them; only that they offer the best profit margins of all the alien tech in our manufacturing facilities. They have made X-Com millions and millions of dollars.

Generating a genre

"But today, XCOM allows for a variety of twists on its formula. Because today – regardless of to whom the credit should be assigned – XCOM is a genre."

Once the Council Of Nations had pushed us into self-sufficiency, we came to a freeing, dangerous realisation: we no longer needed them. So long as we ultimately took the trip to Mars and stopped the heart of the alien command structure, we were no longer financially bound to answer every call for help that cropped up across the planet. X-Com was no longer an international government initiative but a product of capitalism, with all the corporate freedom and cold amorality that shift implied.

On the one hand, revisiting X-Com is a reminder of how deeply Firaxis excavated the game for material. Practically every enemy type has a hi-res equivalent somewhere in the studio's modern adaptations, and even the Avenger – XCOM 2's roving hub – has its roots in the troop transporter at the top of the 1994 game's tech tree.

On the other, it's a reminder that the structure of modern XCOM has introduced a certain amount of stricture, boiling the Geoscape down to a series of decisions that, while clear and compelling, lack the open-endedness of Gollop's original formula. That divergence continues today with Marvel's Midnight Suns, a Firaxis creation that retains the battlefield and strategic layers of XCOM, yet keeps the latter simple to make room for delightfully scripted storytelling. The game couldn't exist without Julian Gollop, but it couldn't have been made by him, either.

If chasing the freewheeling economic and political simulation of the original X-Com, you're best off with Gollop's own successor, Phoenix Point. There, you'll find the trade of weapons and goods modelled alongside a set of factions, which together represent humankind's response to a global crisis: flagellation, denial, bickering and prayer. It's a step forward, in that it challenges you to balance the utilitarian calculations of XCOM with your own values, and consider the world you'd like to see emerge in the aftermath of war. None of which is to say that Firaxis is doing it wrong. Marvel's Midnight Suns is one of the finest games of the past 12 months, and an excellent followup to XCOM in its own right. But today, XCOM allows for a variety of twists on its formula. Because today – regardless of to whom the credit should be assigned – XCOM is a genre.

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine issue 386. For fantastic in-depth features, interviews, reviews, and more, you can subscribe right here or pick up a single issue today.