How do you stop an annoying prankster? By turning the tables and pranking them, of course! It’s the good ol’ rule of ethics: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” If you can’t take someone pranking you, you shouldn’t be playing practical jokes on others, right?

The uncle in this story had to find this out the hard way. As he enjoyed pranking kids by literally bursting their balloons, one family member decided to teach him a lesson. During one party, they rigged the balloons with fart spray, and when temptation hit, the uncle got positively skunkified.

One family member found a way to get back at a balloon-popping prankster uncle

Image credits: LeylaCamomile / Envato (not the actual photo)

They filled the balloons in a balloon arch with fart spray, which resulted in the uncle getting skunkified

Image credits: shotprime / Envato (not the actual photo)

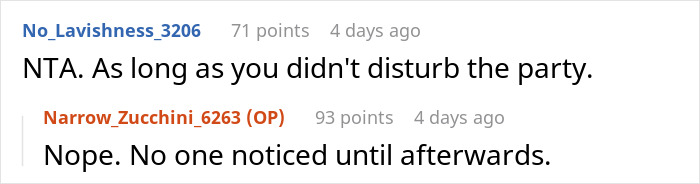

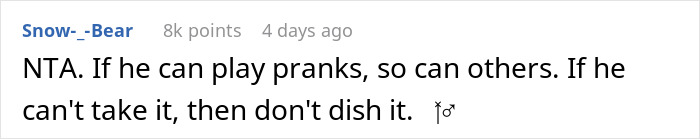

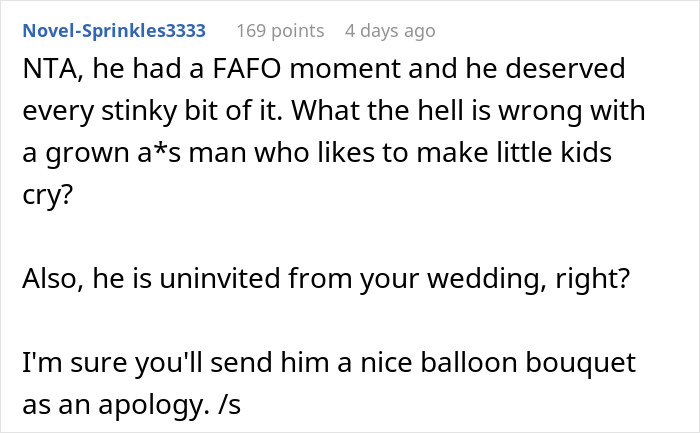

Image credits: Narrow_Zucchini_6263

Adults pranking children can quickly turn into bullying

Image credits: Image by Freepik (not the actual photo)

Practical jokes are not everybody’s cup of tea. While some like sneaking a fart cushion on someone else’s seat, others might find it wildly distasteful. According to a 2021 survey, 47% of Americans say they think April Fool’s Day pranks are annoying, and 45% think they’re funny.

But what about the times the prankster is a grown-up and directs the prank at a child? Are kids always able to understand when something is a joke or might they sometimes take pranks too literally?

Experts say that in order to “get” a prank, a person requires a well-developed “theory of mind.” Children start developing it around the age of 4, and that’s when most kids start to understand what a prank means. From 4 to 12 years old, kids lack critical reasoning, so they’re perfect targets for pranks. And they even might pull some practical jokes of their own.

However, experts also say that there’s a thin line between pranking and bullying. When it’s adults pranking children, it’s often from the realm of “punching-down” humor. When a practical joke violates trust, it’s no longer funny for the one who’s being pranked.

“What we want to do is laugh together – laughing together creates cohesion in social groups,” child psychotherapist Rachel Melville-Thomas explained to the BBC. “If you’re the victim of a prank, [for it to be funny], you have to very quickly join in and go ‘Ah, that was such a clever prank’. It’s hard to see how that happens if you smack someone on the head.”

It’s not entirely clear what’s supposed to be funny to a child about their balloon going boom – it’s not like they can join in on the laughs. They feel rather hurt that a thing they view as akin to a toy just got destroyed. So, were the uncle’s pranks really practical jokes or just a form of bullying?

Both the prankster and the prankee should be able to laugh after a truly good prank

Image credits: Image by Freepik (not the actual photo)

No one enjoys being the butt of the joke. That’s why more people say they like pranking others than being pranked themselves. There’s also a gender component to pranking: the aforementioned survey found that 60% of men under 30 think practical jokes are funny, while only 42% of women in the same age group think the same.

When pranks go too far, they can even be a form of emotional and psychological abuse. When a prank scares or humiliates a person, it’s not really a joke, is it? Professor of Psychology Kathleen M. Pike writes that the relationship between the prankster and the prankee comes into play here.

“The psychology of what makes something a fun-loving prank versus an act of aggression lies in the relationship between participants and the prankster’s motivation. When the outcome of the prank is hurtful instead of humorous, play drains away. It is no longer fun and games but something else masquerading as a prank.”

A good prank is one where both sides can have a laugh afterward. If the intention is to humiliate the prankee, pranks backfire spectacularly. “Many downright nasty and malicious tricks that have no other purpose are sometimes excused as a prank,” senior lecturer in psychology Rachael Sharman writes. “If this happens, ask the pranker a simple question: ‘What about this was funny to me? Break it down and explain it to me.'”

“He deserved every stinky bit of it”: people were delighted by this creative way to get back at a prankster