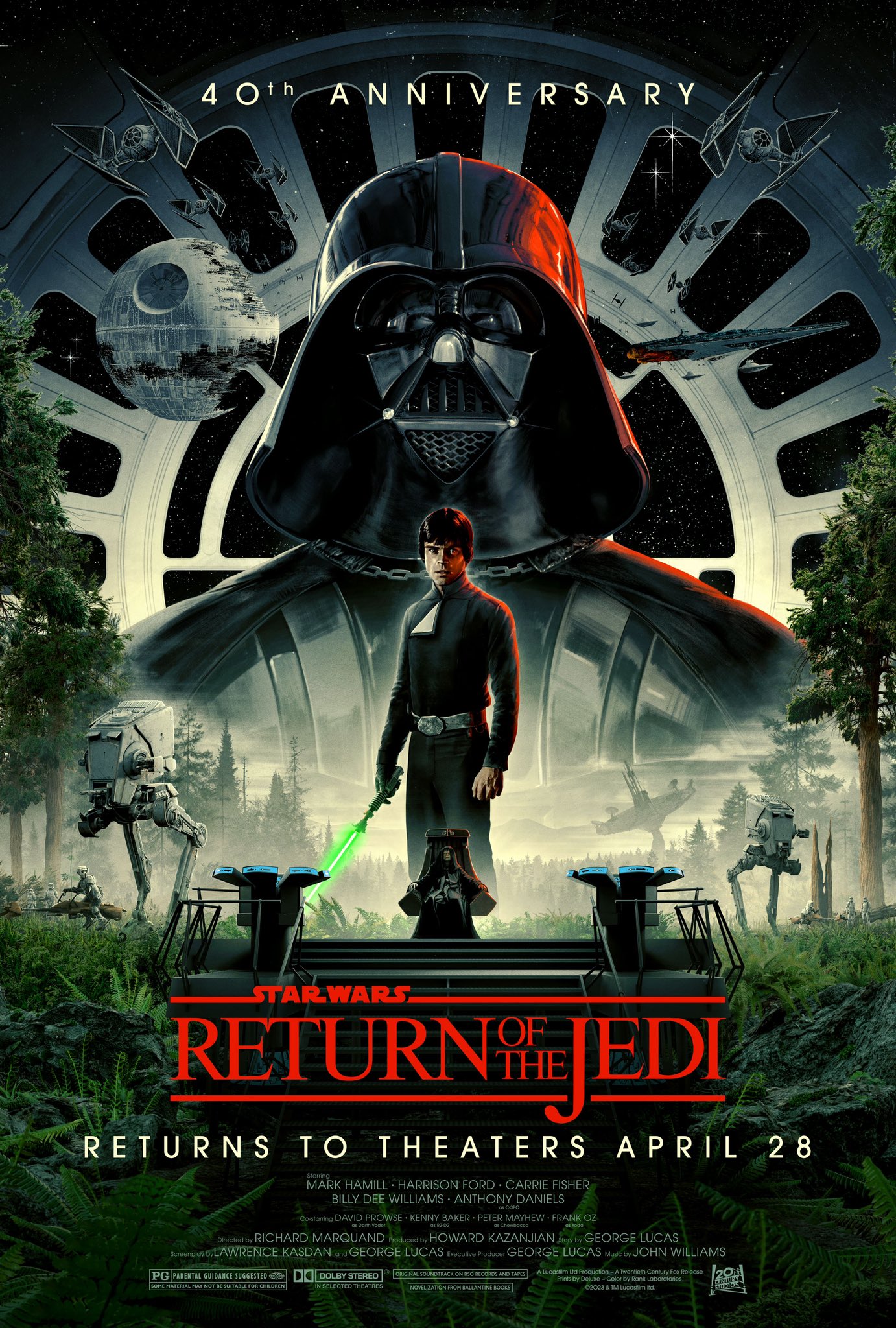

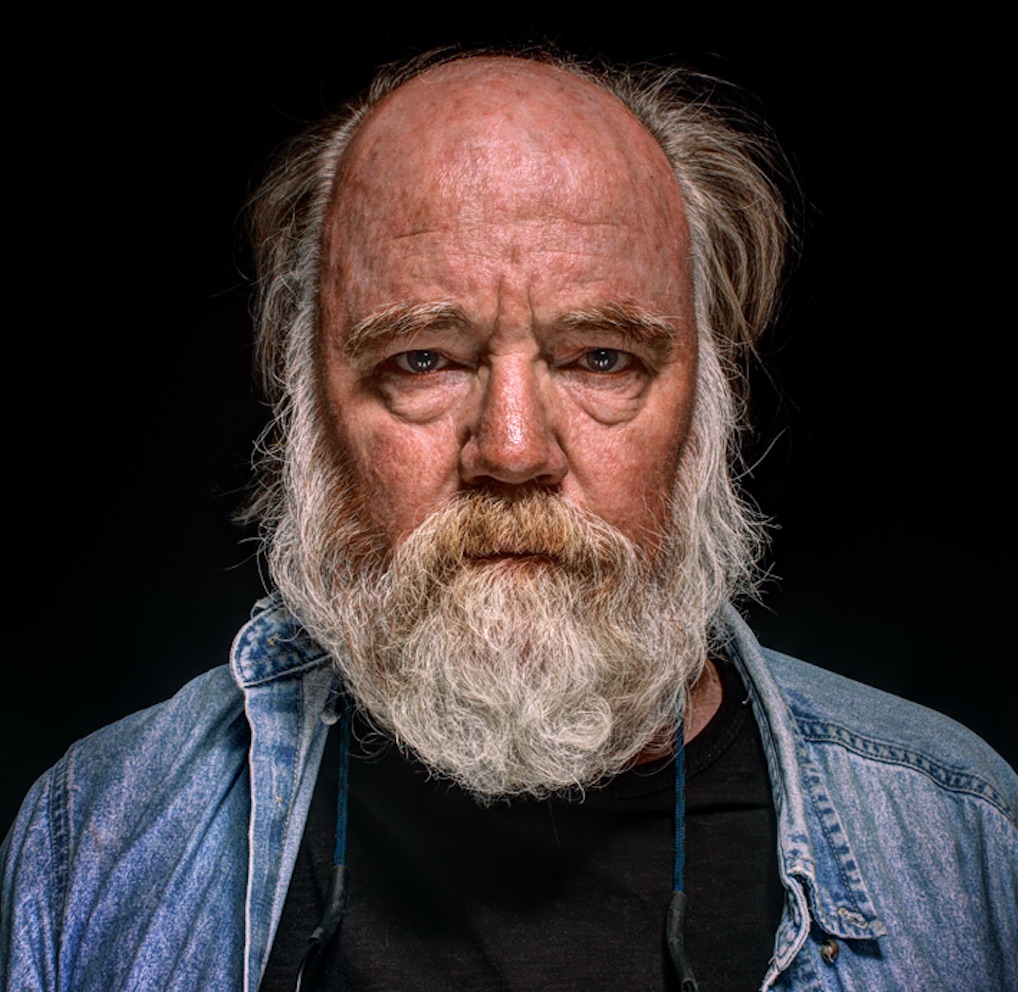

Today marks the 40th birthday of "Star Wars: Return of the Jedi," the last film of the original "Star Wars" trilogy. Who better to help blow out the candles on this landmark occasion than the Oscar and Emmy Award-winning visual effects luminary who helped conjure the magic, Phil Tippett.

Starting in the nascent days of George Lucas's Industrial Light & Magic in a warehouse in Van Nuys, California with a rag-tag crew of geeky geniuses, Phil Tippett created a wealth of old-school "Star Wars" wizardry back in the mid-seventies alongside fellow filmmakers like Richard Edlund, Dennis Muren, Joe Johnston, Lorne Peterson, Ken Ralston, Stuart Freeborn, John Dykstra and many others.

It was Tippett whose stop-motion sorcery was responsible for the "Star Wars" holochess scene aboard the Millennium Falcon in "A New Hope." After that, the effects wizard embedded himself into Hollywood history by breathing life into Taun-Tauns and Imperial Walkers on the icy world of Hoth in "The Empire Strikes Back."

Space.com spoke with Tippett via video from his studio home in Berkeley, California to take a lightspeed leap back in time to the soundstages of "Return of the Jedi" and discover how the smoke and mirrors were positioned on this cherished classic and where his talents for sketching, sculpting, puppeteering, painting and animating were best employed by mastermind George Lucas.

Here on "Return of the Jedi," Tippett struck back with renewed vigor on the arduous threequel shoot to again help manifest iconic characters like Jabba the Hutt, the Rancor pit monster, the Mon Calamari alien Admiral Ackbar, Jabba's sinister henchman Bib Fortuna, and animate the AT-ST "chicken walkers" during the clash with rebels and Ewoks on the forest moon of Endor.

Helmed by Welsh director Richard Marquand under the watchful eyes of George Lucas and released on May 25, 1983, "Star Wars: Return of the Jedi" was a roaring success and played throughout the summer as fans soaked up all the space opera drama for this climactic entry.

"I would chat a lot with Richard [Marquand] between takes, but it was pretty much David Tomblin who I talked with mostly, which was really a great learning experience working with one of the great ADs of all time," Tippet recalls of his time on set. "It ran like a clock, we coordinated with David and when the came time we went on and did our thing. For the Jabba the Hutt sequence I headed up the creature orchestra and denizens in the party, and Stuart Freeborn dealt with Jabba and did the makeup for Bib Fortuna, a character I designed. George [Lucas] was there quite frequently, moving things along and making sure the camera crew knew if they couldn't get it together, their shot wasn't going to be in the movie. He was very persistent.

"It was George's money! He had taken out a giant loan with the Bank of Boston. That was one of the great things about working for George. He was really invested so it wasn't like the studio was paying for it. He moved things along really quickly and in some cases too quickly for me. Sometimes he accepted takes I'd done that I knew I could do better at. And you'd have to plead with him to do another take."

As one of the veteran artists, Tippett's SFX duties on "Return of the Jedi" expanded, as did certain challenges of filming such an intricate big-budget space opera sequel.

"The schedule was the most challenging thing overall for everybody," he notes. "We had to fit five pounds of sh** into a two-pound bag. It all blurs and was literally one thing after the next. Coming up with schedules and flowcharts and that kind of stuff. Like the creatures in Jabba's palace, I'd never done anything like that before. I knew how make costumes around latex and all the processes, but nothing to that scale. I was really deputized by George to take this thing on. He seemed to like what I do and things I come up with. I understood the character of the party and the goings on of Jabba's palace. George hadn't even finished the script yet, or if he had he didn't show me. He said he wanted to do something like the cantina scene only bigger."

"I work primarily with three-dimensional maquettes because George liked getting a visceral hit on what the thing would be if you have an object that's six or eight inches tall. You can turn it and see it in the light and match camera angles as opposed to a series of drawings. Once a week George would come in and I'd show him a half-dozen or so little maquettes we'd made and he'd pick things out. So he'd go, 'This one with the long legs and the snout, that's going to be the singer. Can you put lipstick on it? And this little blue guy, he's going to play the piano.' He pulled out one that I did and he asked, 'What's this?' I told him that's Calamari Man. And he goes, 'Oh, that's going to be Admiral Ackbar.' So he's kind of operating like a documentary filmmaker in a way and going out and casting and looking at interesting characters."

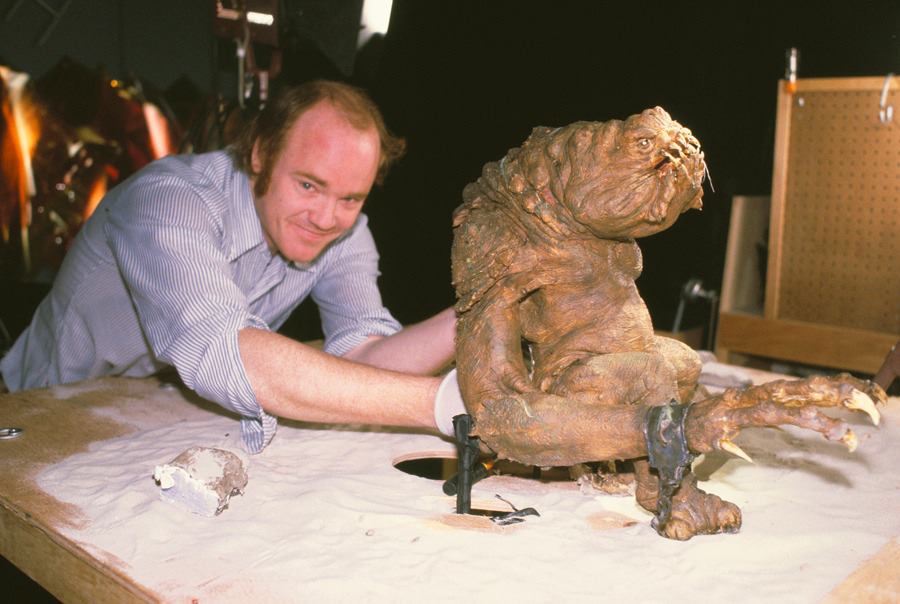

The Rancor pit monster puppet is arguably one of the greatest creatures in the entire "Star Wars" bestiary. That character was initially intended to be a Godzilla-type suit performed by an actor, but that plan was scrapped and deemed unworkable.

"The final design was actually the first design that I did. Joe Johnston, Nilo Rodis and Ralph McQuarrie and I all did designs," says Tippett. "But the creature thing was more in my wheelhouse than in theirs. George said he wanted a big monster in this particular scene that threatens Luke. I designed it to be executed as a stop-motion character so the design would have to be significantly altered to fit a human inside. We didn’t have the time to make a human plaster body and build that up with clay and figure out the adjustments and mold that and cast it in foam rubber."

"So everything was sculpted out of foam with an electric turkey-carving knife and it just didn't look right," he adds. "It looked like crap. We'd get in the outfit and do the pantomime for the thing that acted as our animatic template for the scene. But it was clear it wasn't going to work so George said to do whatever we want to do, but just get it done. We'd run out of time and we felt things were going south. It was Dennis' [Muren] idea to film Rancor as a high-speed miniature as a hand puppet so that's how it was executed in the little time we had left in the schedule.

"The procedure that we used was the antithesis of stop-motion animation, which is sculpting in time and a very slow, meditative mental world. Since you're shooting at like between 76 and 120 frames-per-second at high speed, to make the character look like it has the proper scale, you have to move really quickly. For a four-second shot at 120 frames a second, you have to do all your movements at under two seconds. We were flying blind and shot on film, and didn't have the image-capture technology that exists today, so we didn't see anything until dailies the next day. We did sixty takes and George told us to pick six favorites and send them to editorial."

One of the toughest shots was the stumbling Imperial AT-ST "chicken walker" scene during the Battle of Endor with Ewoks using rolling logs to take the machine down.

"That shot took about six weeks, not counting the miniature background that had to be made by the model shop," he recalls. "It was a pretty good sized set, maybe 20 feet by 20 feet, with a hill and miniature logs and trees. So I figured out what the pantomime would be when the logs roll down the hill and hit the walker's legs to create an imbalance. I had big nails that stuck up from beneath the set where I knew the leg impacts should be. When we rolled the logs down the hill they'd be like a barrier, hit the nails, and that would cue the model guys underneath to pull the nails out and the logs would do their thing. It was shot at about 96 frames-per-second."

"Once the background plate was done I went on a Moviola that had animation peg bars and animation cels. I'd trace out key frames with a black marker where all the logs would be and made a big matte box and put that in front of the camera with animation cels. By that time we'd developed this Go-Motion system to the point where it was very user friendly and I could look through the camera and dial the stepper motors and get the walker legs into the right position. I'd go through and build the performance and go back and refine it over the course of six weeks.

"This shot was very important to George so he didn't give me any guff and let me take as long as it was going to take. We'd discussed the pantomime and how it would move and he saw it was progressing. I like to have fun with these things and one of the things I wanted to do just before the walker was tipping over was have its head turn and look right at the camera. I did stuff like that in 'Starship Troopers.'"

Phil Tippett's latest invention is the phantasmagoric stop-motion animated horror film, "Mad God," currently streaming exclusively on Shudder.