WAY back in 1975, when a young Gordon Brown believed in social democracy, he edited what became the influential Red Paper on Scotland. Brown was elected as rector of the University of Edinburgh in 1972 and it was through this office that he then edited the Red Paper. On an array of matters, the Red Paper set out an alternative, radical and progressive vision for society in Scotland.

Some 20 years on, Brown had his opportunity as chancellor and then prime minister under four Labour governments between 1997 and 2010 to carry that vision forward into practice. He chose not to do so.

Though directed towards Tony Blair in particular, when Margaret Thatcher was asked in 2002 what her greatest achievement was, she said: “Tony Blair and ‘New’ Labour. We forced our opponents to change their minds.”

This applies equally forcefully to Brown. A historic opportunity to right social and economic wrongs was, thus, not taken. Social inequalities widened and capitalism was further deregulated.

This is why, nearly 50 years on from the Red Paper on Scotland, the new book from the Jimmy Reid Foundation is so significant. Called A New Scotland: Building An Equal, Fair And Sustainable Society, the book is a new red – but also green – paper for contemporary Scotland, containing both diagnosis and prognosis.

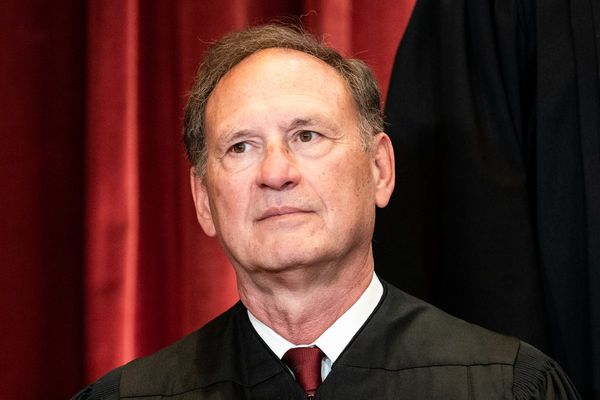

Jimmy Reid died in 2010 after a lifetime of putting his considerable talents towards fighting for social justice. The Jimmy Reid Foundation was set up the following year by the Scottish Left Review magazine which Reid had himself founded in 2000.

Like Brown, Reid was also elected rector for a university in 1972 – this time, at the University of Glasgow. And, just over 50 years ago, on 28 April 1972, he delivered his world-famous rectorial address on the social and economic alienation experienced under capitalism. The address became known as the “rat race” speech.

A New Scotland takes its starting point from the kind of social democratic values and ideas that Reid (below) articulated in that rectorial address because they are still extremely relevant for Scotland today. So, unlike those ideas of Brown, Reid’s still have a cutting edge.

This is because on an array of measures, social and economic inequality still scars society in Scotland, since – despite or maybe even because of – the devolution settlement of 1999 and how it has unfolded. Rates of mortality and educational attainment are only some of the most visible signs that life chances in Scotland are still very heavily influenced by social class.

The Scottish Parliament was premised on the core social democratic principle that state action could produce a more civil, decent and equal society by intervening in the processes and outcomes of market capitalism (which is now called neoliberalism). Fairness and equity were to be the watch words.

But it is clear that the Scottish Parliament is not proving to be the shield of protection from the cold, neoliberal winds of economic change that many citizens hoped it would be. This constitutes the latest instalment of the long crisis of social democracy. It, therefore, also represents a crisis of social and economic justice too.

In a process begun by preceding Labour-LibDem coalition Scottish Governments under the tutelage of “New” Labour, each consecutive Scottish Government has now retreated from this core principle, increasingly succumbing to the ideology of neoliberalism – essentially, the belief that the capitalist free market is the best means for organising society and aligning supply and demand.

The SNP-led Scottish Government is the latest incarnation of this trajectory. Boiled down to the essentials, it believes that a successful capitalist economy in Scotland is necessary to provide the wealth – especially in the form of tax revenue – to provide for increased living standards and a limited welfare state. Covid-restrictions aside, almost nothing is allowed to get in the way of capitalism being allowed to provide this role – even if it means pain and sacrifices for the many and riches and influence for the few.

In this context, more than 60 academic and activist contributors worked together as teams to provide A New Scotland with 25 chapters on almost all aspects of society, economy and politics in Scotland.

In regard of their expertise, they were asked four questions: what’s wrong with the current situation; why is the current situation like this; what are the progressive, radical alternatives; and how can these alternatives be realised? All the contributors begin from the starting point that the neoliberal epoch that we live under is the single biggest and, critically, systemic cause of our social ills.

Then they move to look at how state and civil society has responded. While there is recognition that efforts by successive Scottish Governments since devolution have been made to reduce inequality, this is not tantamount to trying to achieve social and economic justice. Instead, it amounts to meagre and marginal moderation of market outcomes.

Some contributors believe significant degrees of inequality still exist because of the actions of successive Scottish Governments. Put another way, and contrary to pronounced policies, Scottish Governments have chosen not to act to challenge the vested interests creating and perpetuating social inequality and have even cooperated in their perpetuation.

In the analysis of some chapters, this trajectory has sometimes been attributed to the limited nature of the devolved settlement (in terms of the powers of the Scottish Parliament) and sometimes to the choices made by the dominant, left-of-centre, mainstream parties in the Scottish Parliament. All mainstream left-of-centre political parties (Greens, Labour, SNP) in Scotland subscribe to the political ideal of social justice, best epitomised by the pursuit of a “fairness” agenda.

This is part of the problem because, conceptually, there is such elasticity to social justice and its subsidiary, “fairness”. And, a neoliberal narrative has colonised what most politicians now mean by “fairness” and social justice.

So, social democracy in Scotland has been pushed back to a shrivelled, shrunken core by neoliberalism. Often the extremely limited new state intervention is to salvage enterprises from the ravages of capitalist market forces, rather than pro-actively taking control of strategic sectors for public benefit.

Other than the Scottish Greens and, a short-lived period, Scottish Labour under Richard Leonard’s leadership, social democracy barely exists as a political ideal in Scotland.

The SNP claims on its website to be “Centre left and social democratic” but neoliberalism in its various guises (like the “social liberalism” of the SNP) has captured and colonised the public and private institutions of economic, political and social governance in Scotland.

For some, all this points the way to independence rather than enhanced devolution, especially as the “British road” to social democracy (under the Corbyn project) has fallen by the wayside.

But if the case for independence is to be a strong one in terms of achieving social and economic equality, it must be predicated on breaking from these contemporary conventions and constraints in order to convincingly answer the key questions: independence from what and from whom, and independence for what and for whom?

If the answers do not converge around economic independence for the mass of the population, namely, the working class, from the diktats of capitalism then independence will be a pyrrhic victory. It may seem that political and constitutional freedom will have been gained but the realpolitik will be that neoliberal capitalism will still dominate, pervading almost all aspects of our lives.

It would, therefore, be somewhat naïve to expect the SNP, given its record in office as well as its policy pronouncements on the future of Scotland, to be the party which will make this break from neoliberalism. But equally, the same argument can be made about the efficacy of Scottish Labour to pursue social democracy – should it return to anything approaching political dominance under enhanced devolution.

This leaves the issue of the Scottish Greens. As a small party, it is nowhere near being in contention to be a major player (even on environmental issues) and the omens of its compromises since August 2021 as part of the SNP-led Scottish Government set up are not encouraging.

For social and economic justice to become useful and meaningful, the principles of distributive justice must become dominant. These span elements of economic, social, environmental and political justice and encompass norms of equity, equality and egalitarianism as well as the components of power, resources, need, costs and responsibility.

More concretely, distributive justice is based upon stipulating qualitative and quantitative aspects of outcomes in terms of setting maximum relativities between social intersections of class, gender, age and race. Here, equality of access replaces the spurious notion of equality of opportunity so that equalities of outcome can be achieved, where just distribution over time then becomes less dependent upon the greatest benefit necessarily being given to the least advantaged as there is both levelling up and down.

One of the key ways of delivering distributive justice is to have pre-distribution rather than re-distribution. The pre-distribution version of social democracy would see far greater emphasis put upon controlling the processes by which capitalism functions so that less post facto intervention is needed.

Examples might be maximum wages or minimum incomes to reduce wage inequality or rent and price controls rather than providing housing benefit or Universal Credit.

The significance of pre-distribution is that it rethinks traditional social democracy because it goes beyond merely suggesting the alternative to the neoliberal market economy is the co-ordinated market economy. Much centre-left thought has been trapped within this “varieties of capitalism” thinking, where the political lesson being proffered is that German, Japanese and Swedish forms of capitalism are, thus, preferable to Australian, British and American capitalism.

The chapters in A New Scotland answer the aforementioned four questions in different ways. Those in the first section provide foundational macro-perspective chapters which cover thematic concerns of neoliberalism, capitalism, social democracy, socialism and eco-socialism.

These are followed, in the second section, by chapters specifically considering issues of application and practice. This covers the likes of health, education, housing, transport, work, gender and race.

The third section comprises chapters which draw the preceding threads together to examine the basis of points of departure.

Put more pointedly, these chapters begin to consider the issue of the social forces needed to act as agents for change to achieve a radical transformation of society in Scotland. And, although the contributors express their respective perspectives on independence and enhanced devolution, they do not let these get in the way of outlining what can be done in the here and now with existing powers.

Edited by Gregor Gall, A New Scotland: Building an Equal, Fair and Sustainable Society is published in association with Pluto Press on May 20, 2022, priced £14.99. Professor Gregor Gall is director of the Jimmy Reid Foundation