For many people, the aroma of freshly brewed coffee is the start of a great day. But caffeine can cause headaches and jitters in others. That’s why many people reach for a decaffeinated cup instead.

I’m a chemistry professor who has taught lectures on why chemicals dissolve in some liquids but not in others. The processes of decaffeination offer great real-life examples of these chemistry concepts. Even the best decaffeination method, however, does not remove all of the caffeine – about 7 milligrams of caffeine usually remain in an 8-ounce cup.

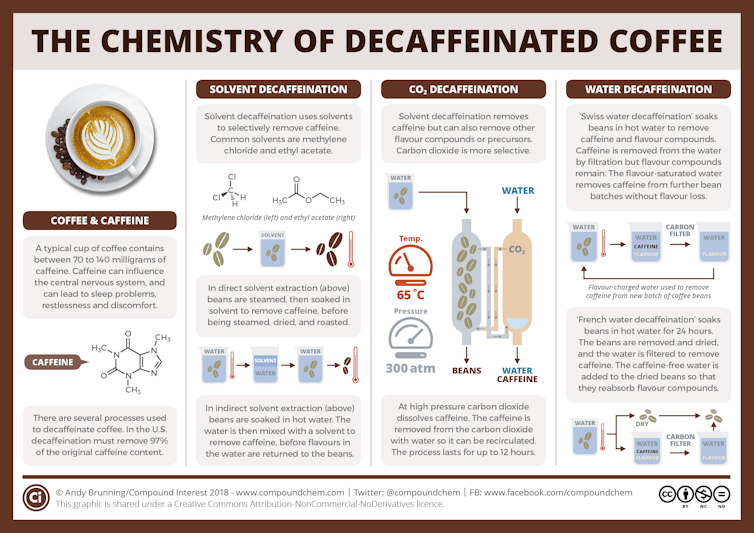

Producers decaffeinating their coffee want to remove the caffeine while retaining all – or at least most – of the other chemical aroma and flavor compounds. Decaffeination has a rich history, and now almost all coffee producers use one of three common methods.

All these methods, which are also used to make decaffeinated tea, start with green, or unroasted, coffee beans that have been premoistened. Using roasted coffee beans would result in a coffee with a very different aroma and taste because the decaffeination steps would remove some flavor and odor compounds produced during roasting.

The carbon dioxide method

In the relatively new carbon dioxide method, developed in the early 1970s, producers use high-pressure CO₂ to extract caffeine from moistened coffee beans. They pump the CO₂ into a sealed vessel containing the moistened coffee beans, and the caffeine molecules dissolve in the CO₂.

Once the caffeine-laden CO₂ is separated from the beans, producers pass the CO₂ mixture either through a container of water or over a bed of activated carbon. Activated carbon is carbon that’s been heated up to high temperatures and exposed to steam and oxygen, which creates pores in the carbon. This step filters out the caffeine, and most likely other chemical compounds, some of which affect the flavor of the coffee.

These compounds either bind in the pores of the activated carbon or they stay in the water. Producers dry the decaffeinated beans using heat. Under the heat, any remaining CO₂ evaporates. Producers can then repressurize and reuse the same CO₂.

This method removes 96% to 98% of the caffeine, and the resulting coffee has only minimal CO₂ residue.

This method, which requires expensive equipment for making and handling the CO₂, is extensively used to decaffeinate commercial-grade, or supermarket, coffees.

Swiss water process

The Swiss water method, initially used commercially in the early 1980s, uses hot water to decaffeinate coffee.

Initially, producers soak a batch of green coffee beans in hot water, which extracts both the caffeine and other chemical compounds from the beans.

It’s kind of like what happens when you brew roasted coffee beans – you place dark beans in clear water, and the chemicals that cause the coffee’s dark color leach out of the beans into the water. In a similar way, the hot water pulls the caffeine from not yet decaffeinated beans.

During the soaking, the caffeine concentration is higher in the coffee beans than in the water, so the caffeine moves into the water from the beans. Producers then take the beans out of the water and placed them into fresh water, which has no caffeine in it – so the process repeats, and more caffeine moves out of the beans and into the water. The producers repeat this process, up to 10 times, until there’s hardly any caffeine left in the beans.

The resulting water, which now contains the caffeine and any flavor compounds that dissolved out from the beans, gets passed through activated charcoal filters. These trap caffeine and other similarly sized chemical compounds, such as sugars and organic compounds called polyamines, while allowing most of the other chemical compounds to remain in the filtered water.

Producers then use the filtered water – saturated with flavor but devoid of most of the caffeine – to soak a new batch of coffee beans. This step lets the flavor compounds lost during the soaking process reenter the beans.

The Swiss water process is prized for its chemical-free approach and its ability to preserve most of the coffee’s natural flavor. This method has been shown to remove 94% to 96% of the caffeine.

Solvent-based methods

This traditional and most common approach, first done in the early 1900s, uses organic solvents, which are liquids that dissolve organic chemical compounds such as caffeine. Ethyl acetate and methylene chloride are two common solvents used to extract caffeine from green coffee beans. There are two main solvent-based methods.

In the direct method, producers soak the moist beans directly in the solvent or in a water solution containing the solvent.

The solvent extracts most of the caffeine and other chemical compounds with a similar solubility to caffeine from the coffee beans. The producers then remove the beans from the solvent after about 10 hours and dry them.

In the indirect method, producers soak the beans in hot water for a few hours and then take them out. They then treat the water with solvent to remove caffeine from the water. Methylene chloride, the most common solvent, does not dissolve in the water, so it forms a layer on top of the water. The caffeine dissolves better in methylene chloride than in water, so most of the caffeine stays up in the methylene chloride layer, which producers can separate from the water.

As in the Swiss water method, the producers can reuse the “caffeine-free” water, which may return some of the flavor compounds removed in the first step.

These methods remove about 96% to 97% of the caffeine.

Is decaf coffee safe to drink?

One of the common solvents, ethyl acetate, comes naturally in many foods and beverages. It’s considered a safe chemical for decaffeination by the Food and Drug Administration.

The FDA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration have deemed methylene chloride unsafe to consume at concentrations above 10 milligrams per kilogram of your body weight. However, the amount of residual methylene chloride found in roasted coffee beans is very small – about 2 to 3 milligrams per kilogram. It’s well under the FDA’s limits.

OSHA and its European counterparts have strict workplace rules to minimize methylene chloride exposure for workers involved in the decaffeination process.

After producers decaffeinate coffee beans using methylene chloride, they steam the beans and dry them. Then the coffee beans are roasted at high temperatures. During the steaming and roasting process, the beans get hot enough that residual methylene chloride evaporates. The roasting step also produces new flavor chemicals from the breakdown of chemicals into other chemical compounds. These give coffee its distinctive flavor.

Plus, most people brew their coffee at between 190 F to 212 F, which is another opportunity for methylene chloride to evaporate.

Retaining aroma and flavor

It’s chemically impossible to dissolve out only the caffeine without also dissolving out other chemical compounds in the beans, so decaffeination inevitably removes some other compounds that contribute to the aroma and flavor of your cup of coffee.

But some techniques, like the Swiss water process and the indirect solvent method, have steps that may reintroduce some of these extracted compounds. These approaches probably can’t return all the extra compounds back to the beans, but they may add some of the flavor compounds back.

Thanks to these processes, you can have that delicious cup of coffee without the caffeine – unless your waiter accidentally switches the pots.

Michael W. Crowder does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.