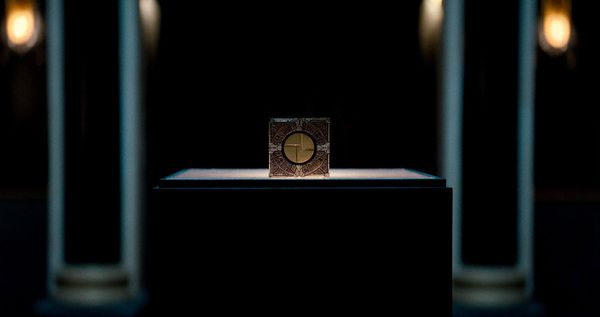

In 1987, Clive Barker's "Hellraiser" reinvigorated a genre that was, at that time, dominated by homicidal slashers. Barker's story, based on his novella "The Hellbound Heart," countered that trend by presenting entirely sane villains motivated by unquenchable desire as opposed to unhinged mania, lured to their doom by a mysterious puzzle box.

A hedonist named Frank Cotton dares to play with it and is ripped apart as he's pulled into another dimension. Frank returns to this existence, in parts. It takes his brother's sexually dissatisfied wife Julia to bring him back piece by piece by luring unsuspecting victims to him so he can feed on them.

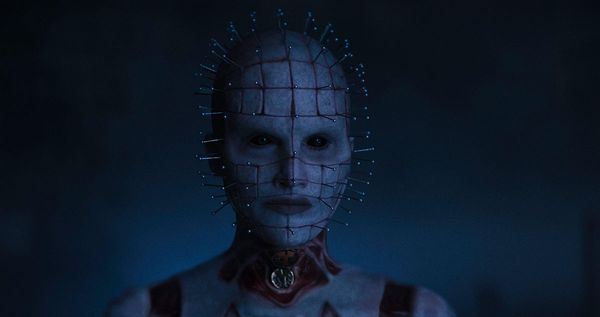

Grotesque as Frank and Julia are, the supernatural creatures pursuing him, the Cenobites, are the film's true stars, beings from a place where pleasure and pain are indistinct. Doug Bradley's lead Cenobite, who came to be known as Pinhead, became synonymous with a franchise that came to redefine body horror. Between his elegant demons and the overt eroticism intertwined with gory terror, the nightmare wrought by "Hellraiser" proved difficult to recapture in its sequels.

That may be why its remake took 15 years and many changes behind the scenes before David Bruckner took on the role of directing it.

His vision, which is now streaming on Hulu, trades the original's flirtation with sexual kink for a story about addiction, regret, and lament centering on an aimless young woman named Riley (Odessa A'zion). A recovering addict struggling to get back on her feet, Riley comes to possess the puzzle box as part of a misadventure embarked upon in anger.

Soon afterward, it starts to consume everything around her.

This "Hellraiser" follows a familiar framework, but the Cenobites have been updated, and upgraded, in a fascinating way, including casting Jamie Clayton ("The L Word: Generation Q," "Sense8") as Pinhead, a choice that injects glamour into the chilling dread that they and the other Cenobites evoke. In a recent conversation with Salon, Bruckner talked about the choices he and screenwriters Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski made to modernize Barker's story while taking an extreme effort to stay true to the original's vision, and refrain from tearing its soul apart.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

"Hellraiser" is one of my favorite horror films from back in the day. Was it a favorite of yours as well?

I discovered it a little bit late. As a young teenager who was just getting into horror, "Hellraiser 3" was my gateway drug, which was very different than the original movie. And so it was a little bit later that I discovered the series and . . . developed an appropriate regard for it. But I know it's sacred territory for horror fans.

How did going back to the original change your impression of the series, and not only that, of its mythology?

Well I was young when I saw "Hellraiser 3," and it was frightening. And I think the dread that was induced – being trapped at a nightclub, an there being no escape – was in and of itself, pretty frightening. But the imagery was something that really, really stuck with me.

Later, when I started to get into horror in a different way. I went back and watched "Hellraiser" and "Hellraiser 2" and then years later, read the novella. Obviously, I understood it to be something much deeper, much more layered. The sexual subtext was something that I missed in Part 3, and just the sheer inventiveness of it and the kinds of themes that are tackled were things that, you know, I absolutely marveled at.

I think one of the things that "Hellraiser" did so well was generate all of these ideas, not only in terms of how pleasure is perceived, but also in terms gender norms and gender identity in society that I think is otherwise difficult to translate into a horror film. I'm wondering how much of that aspect of it translated into the script for the 2022 version?

In the original film, I think part of the reason that the horror has the impact that it has is because the audience is complicit in a pretty fascinating dark game. I would argue that Julia is the protagonist of the original film: You're on a journey alongside her where you're trying to decide whether you want to reconstitute your dead, would-be lover, who happens to be the brother of your husband – who is coming together in the attic in this really gruesome way.

You have to align yourself in one way or another with her desire for him, and yet you're looking at these really grotesque images.

All that is to say that this is something so unique about the first film in a way that's – it's very hard to get a movie across the line in 2022 in the American studio system that operates quite like that. There's a lot of pressure to create "likable" characters, and I put it in quotes because likability is not my favorite term, and it doesn't necessarily have anything to do with empathy.

It's difficult to maneuver a film into that system that's going to have an erotic charge to it when you're combining it with violence on this level. We needed to find a kind of an adjacent conversation to sort of get through the door and bringing this film to life. And I felt that addiction was a worthy topic.

It's an interrogation of how we negotiate our desires, and when the things that we're seeking can become a replacement for managing the difficulties in life. It's not necessarily about identity in the same way. But it did feel topical, and it felt like I thought, a worthy addition to the conversation.

One of the things that the script did that I thought was so fascinating was it broadened the possibilities of human experience that were contained in the box. So it wasn't just a metaphor for pleasure, desire, identity, whatever you're seeking when you open this thing, but that it was also could be translated into a doorway to the extremity of any human pursuit.

I want to just back up to what you said about seeing Julia as the protagonist. You realize people are going to liken that to saying, "Johnny is the true hero of 'The Karate Kid.'"

"I find guilt to be really interesting in horror."

That's purely in terms of narrative function. She moves the story forward, you know. Kirsty is an innocent who comes in and particularly activates towards the end of the film. But it's not about a moral alignment, necessarily. It's about what moves the story. By spending time alongside her, in her shoes, discovering Frank, and you can't help but empathize with her predicament one way or another, whether she's making choices you want her to make or not. I think that's part of what makes her such a fascinating character.

That makes me wonder how that translated into the way you perceive the main characters in the 2022 version.

Well, we wanted to find somebody that was at some sort of tension. We wanted somebody that was flawed, troubled, to be able to play some level of melodrama. And I liked Riley because she was hot from the top, like she was she was gonna come into every scene willing to have a fight. And I thought that infused the film with a kind of necessary energy that just felt appropriate.

Among all the analyses that have been written about the original movie, a common thing that's pointed out is that Kirsty [Frank Cotton's niece and Julia's stepdaughter] is, in a way, the Final Girl, but not the same as the typical Final Girl. And Riley fits that, but in a very interesting way in that, as you say, it's not about moral alignments. The decisions she makes, the trouble she gets into in the first place is based on her addiction and her anger. How much of that idea of subverting the trope of the Final Girl play into her development?

I didn't think about this much in Final Girl terms, necessarily. And I think there's something of a psychodrama at play where she's concerned.

I find guilt to be really interesting in horror. It can be a very powerful and relatable emotion that is never the thing you show up for when you go to the movies. But it contains a kind of dread, and a kind of a yearning for responsibility and growth.

In the context of Hellraiser, the jury's out on where Riley ends up ultimately. The morality of it is fairly neutral, as are the Cenobites. This is not a story about somebody getting it right, necessarily. This is a story about somebody being in tension between the things that relieve her of the burden of life and the responsibilities. They're in the things that feel good to her, whether they might be you know, a bottle of pills, or this this guy, Trevor that she's drawn to, or shiny puzzle box. And I love being at the intersection of that. And I thought the Cenobites were wonderful guides to tag us in the other direction.

Now, of course, the Cenobites are when people think about "Hellraiser," and associate Doug Bradley with playing Pinhead. You have a version of Pinhead and the female Cenobite. But there are definitely some more original creations. From what I can see, how much how did you find that balance between honoring what people expect from "Hellraiser" and the Cenobites, and maybe introducing some new Cenobites into this mix?

Just as a fan and a lover of the basics of a genre movie, if I'm going to show up for a "Hellraiser" movie, I want to see some new creations in this world. And I want someone to take me a little bit further into it. The Cenobites were a huge part of that.

We knew we had to do Pinhead. That was the biggest challenge, obviously, because it's so iconic and Doug Bradley's performance is so incredible, and nuanced and memorable. And we were very lucky to find Jamie [Clayton].

And we wanted to pay our respects to the Chatterer, obviously. But you know, the biggest change obviously, was in the design. The Cenobites are so unique as monstrous creations. There's such an irony to the imagery: It's abhorrent, but they're also gorgeous. There's a vanity and a regality, but there's also something completely grotesque. It was a blast to kind of dive into that. I don't know if we struck the right balance. You know, time will tell.

There are two things that I noticed. One was the fact that in the original, there's that whole idea of them having these almost the monastic robes. But that it looks like you dispense with that almost entirely. Am I right?

And the second one was that in terms of the glamour, the piercings, each of them had the little have the small, almost decorative – I don't know if they're silver or pearl, but they're very, they look beautiful. And yet they're piercing their flesh, their faces.

Cenobites are "demons to some, angels to others."

Yeah. You mentioned the monastic robes, like the black leather Pinhead wears is something of a cassock in the original. That iconography remains, but it's all born of flesh. It is their own flesh. In essence, they are their own leather.

And the reason for the change came from a few different things. On one hand, we felt that our ideas of the kind of sadomasochistic, you know, BDSM iconography had maybe changed over time. I imagine that in 1987, to see these images for the first time, is obviously quite transgressive. And you know, Clive was able to wheel this stuff out and scare the hell out of suburbanites.

But 35 years later, it's all a bit more aboveboard . . . it's also infiltrated so many different avenues of pop culture, it's present everywhere in fashion, we've seen it repeated a million times over. I was joking, my mom reads "Fifty Shades." I think at this point in time, it's hard to get something as shocking from it.

And so we started to play around with ideas that began in earnest just in, how do we do this? What is this to us these days. We started to push body modification a little bit further, we started to ask ourselves questions of what if we thought about the Cenobites not being tethered to an earthly subculture, but having been unchained, so to speak, having the freedom to really explore their pursuits, in ways that we hadn't thought about.

And along that path, we stumbled on this idea that they would be so modified, that you could start to think of their own flesh as tailored, like clothing, that you would have the kind of glitz and glamour of a runway model, but it would be born out of this sensational pursuit that each of them enjoy in their own way.

You know, [they're] "demons to some, angels to others." We sometimes we found ourselves tipping a little bit more on the angelic side. Maybe that comes from our reverence so many years later.

And we have such a different understanding of gender identity today in 2022, than back when the film first came out. Did you purposely want the Cenobites to be less identifiable as male and female, as more non-binary this time?

Yeah, I think we're inspired a bit by "The Hellbound Heart," which describes the Cenobites initially, as being androgynous to some degree. But then there are also certain gendered qualities from a design perspective, like in just in the sense that we were, you know, trying something beautiful in them that would feel angelic to us, that pursuing androgynous ideas or playing around with concepts of gender felt more advanced to us than human culture, in many ways.

I've always thought of the Cenobites as having gone farther than us in so many different ways. And part of what's terrifying about them is that they have come back to us and stand here on the threshold and are the reaching out to you. They're inviting you into this. And of course, that's a terrifying step to take.

But there may be untold rewards in that direction. And so, part of that was fitting. But then also, the more we got into it, the more we realized that to make that as some kind of overstatement would maybe miss the point. The world felt bigger than that, and we didn't want to boil anything down to that to anything that specific.

I think they're each their own creation, I would take each Cenobite and let each of them speak differently to those ideas.

"Hellraiser" is now streaming on Hulu. Watch a trailer via YouTube.