Earlier this year, in only his second week in office, President Joe Biden signed several executive orders aimed at reversing some of the Trump administration’s harshest immigration policies. In June, the Biden administration released a “progress report” on its “relentless pursuit of reunifying families that were cruelly separated during the previous administration.” The report identified 2,127 separated children not yet reunited with their families. According to the Women’s Refugee Commission, as of August, the Biden administration has reunited only 40 families that have been separated from each other for years. Slow, painstaking progress is being made, but the nightmare is far from over for many families.

Whenever I hear any news about our treatment of migrant children from the global south, I think about the photograph of a small girl and her father face down in the Rio Grande. Their names were Óscar and Valeria. In the photo, Valeria is wearing red pants, her little body is tucked into her dad’s black t-shirt, her little arm wrapped around his back.

It’s difficult to fathom the desperation a parent must feel to tuck their infant inside their shirt and wade into a wide, unforgiving river. Óscar was trying to cross the Rio Grande from Mexico to Texas with his daughter to seek asylum. Like so many others, they’d been turned away in Matamoros by U.S. Border Patrol officers.

Along with the 2018 photo of a young girl named Yanela crying as a U.S. Border Patrol officer interrogated her mother, the photo of Óscar and Valeria became yet another visual symbol of Donald Trump’s cruel “zero tolerance” policies at the southern border. It took only eight days of sustained public outrage after the photo of Yanela was published for the Trump administration to formally rescind its family separation policy. The cover of the July 2, 2018 issue of Time magazine showed former President Trump looking down on Yanela with his trademark smirk. Against a bright red backdrop, white letters read: Welcome to America. (The Texas Observer has chosen not to republish either image out of respect for their families and loved ones).

The photographs of Yanela and Valeria broke through to a largely apathetic American public in large part because they reminded us of our own daughters, granddaughters, nieces. In a photo taken months before her death, Valeria sits smiling on her father’s lap. With her curly black hair and pink bow, she looked just like my young daughter, Sophia.

But if the images of Yanela and Valeria opened our eyes to the cruelty of the Trump administration’s immigration policies, they ultimately failed to transform long-standing dominant narratives about immigration and the southern border. Whatever gains for empathy these stories achieved among the American public, they did so because we cannot resist the allure of innocence; we are captivated by a “through no fault of their own” morality. It’s as if we weigh the dead on an invisible scale of innocence, which we usually measure by age. Except when we don’t: Trayvon Martin. Tamir Rice. Adam Toledo. Ma’Khia Bryant.

Consider another photo, from 2016, of the remains of a migrant who died crossing into Texas, likely from dehydration. You may not have seen it. It didn’t go viral. It didn’t make the cover of Time. Probably because this migrant was an adult who broke the law by crossing into the United States without proper papers.

This wouldn’t have happened if they’d just followed the law. I hear this every time a Black or brown person is imprisoned or killed during an interaction with law enforcement or the criminal legal system. The actual circumstances never seem to matter. We thought he had a gun, police say. She was resisting.

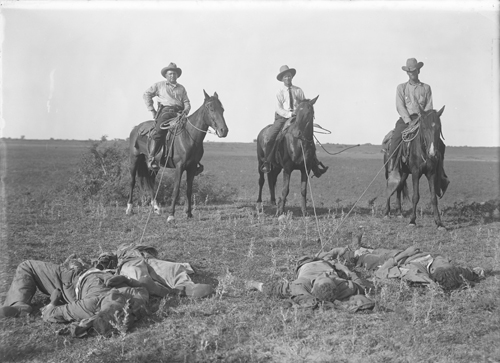

I’m thinking of another photograph, from 1915, of three Texas Rangers on horseback looking down at the bodies of four Mexican men they murdered. The Rangers were known to leave the bodies of their victims exposed as a warning to other Mexicans and Tejanos resisting the Anglo takeover of South Texas throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A Texas Ranger patrol song from around 1900 went like this: “O bury me not on the long prair-ee / where the wild coyotes will howl o’er me! / In a narrow grave just six by three / where all the Mexkins ought to be!”

The 1915 photo and the 2016 photo were both taken in the flat thorny landscape of the South Texas borderlands. The open land frames the killing. The horizon between the land and sky are the same, as is the space between the living and the dead. Taken a hundred years apart, the images reveal the deep roots of an enduring border narrative, one that views migrants from the global south as criminals that require constant policing, and the southern border as a warzone that requires permanent militarization. Indeed, this summer, Texas Governor Greg Abbott deployed 1,000 state troopers to the borderlands as part of Operation Lone Star which, according to the state’s Department of Public Safety, “continues its presence, including air, ground, marine and tactical security assets, along the border to combat the smuggling of people and drugs into Texas.”

The photographs are important because they implore us to make connections that many Americans are not ready, or simply refuse, to make. They remind us that cruel immigration policies are part of a broader criminal legal apparatus founded on the alienation, criminalization, and dehumanization of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color. “Immigrant detention centers” are actually prisons, and seeing the tragedy of family separation only in the context of immigration enforcement obscures the fact that mass incarceration has been separating and destroying families for generations. The photographs demonstrate that the cruelty we see today is rooted in long histories of white supremacist violence. They remind us that the disposing of BIPOC people deemed uninnocent and therefore undeserving of life, dignity, or humanity, is nothing new. It’s an American tradition.

To break this tradition, the American public not only needs to better understand why some people fear the police or must flee their home countries, we must also recognize that the very narratives that structure our understanding of guilt and innocence have little to do with the law or morality and everything to do with protecting white supremacy at all costs. If we are to address migration and violence without creating tidal waves of devastation and trauma in families and communities on both sides of the southern border, we must abandon the lethal formula of innocence and disposability. Until we do, the horrific deaths at the southern border and in the streets of cities across the U.S. will only amount to fleeting ruptures in dominant narratives.

I’m thinking of one more image, the artist Christina Maria Patiño Houle’s reimagination of the photograph of the Texas Rangers and the dead Mexicans. Patiño Houle puts herself in the positions of the Rangers on horseback and the dead Mexican men on the ground. By claiming the image as her own, Patiño Houle mutes the destructive power of the original photo, asserts her existence as a descendant of the land, and reclaims narratives about the borderlands away from those that bolster white supremacy and toward those that reflect the resistance and survival of BIPOC people, families, and communities.

Executive orders—even good ones—won’t change dominant narratives about immigration and the border. And even good policies won’t inspire us to build strong communities that have no need for policing or mass incarceration. Transforming narratives results from storytelling and memory work by survivors, activists, organizers, artists, writers, and others from communities directly impacted by generations of white supremacist violence. Patiño Houle is part of a cohort of storytellers and memory workers reclaiming and transforming border narratives. Efforts like this, as well as liberatory memory work happening here in Texas and across the country, challenge us to dig deeper, look closer, and resist against the widespread loss and suffering that is happening all around us, in our names.