The rigid structures of language we once clung to with certainty are cracking. Take gender, nationality or religion: these concepts no longer sit comfortably in the stiff linguistic boxes of the last century. Simultaneously, the rise of AI presses upon us the need to understand how words relate to meaning and reasoning.

A global group of philosophers, mathematicians and computer scientists have come up with a new understanding of logic that addresses these concerns, dubbed “inferentialism”.

One standard intuition of logic, dating back at least to Aristotle , is that a logical consequence ought to hold by virtue of the content of the propositions involved, not simply by virtue of being “true” or “false”. Recently, the Swedish logician Dag Prawitz observed that, perhaps surprisingly, the traditional treatment of logic entirely fails to capture this intuition.

The modern discipline of logic, the sturdy backbone of science, engineering, and technology, has a fundamental problem. For the last two millennia, the philosophical and mathematical foundation of logic has been the view that meaning derives from what words refer to. It assumes the existence of abstract categories of objects floating around the universe, such as the concept of “fox” or “female” and defines the notion “truth” in terms of facts about these categories.

For example, consider the statement, “Tammy is a vixen”. What does it mean? The traditional answer is that there exists a category of creatures called “vixens” and the name “Tammy” refers to one of them. The proposition is true just in the case that “Tammy” really is in the category of “vixen”. If she isn’t a vixen, but identifies as one, the statement would be false according to standard logic.

Logical consequence is therefore obtained purely by facts of truth and not by process of reasoning. Consequently, it can’t tell the difference between, say, the equations 4=4 and 4=((2 x 52 ) -10)/10 simply because they are both true, but most of us would notice a difference.

If our theory of logic can’t handle this, what hope do we have to teach more refined, more subtle thinking to AI? What hope do we have of figuring our what is right and what is wrong in the age of post-truth?

Language and meaning

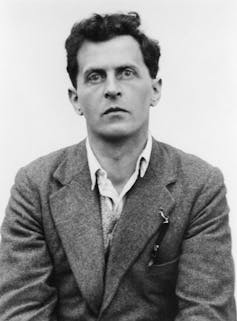

Our new logic better represents modern speech. The roots of it can be traced to the radical philosophy of the eccentric Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who in his 1953 book, Philosophical Investigations, wrote the following:

“For a large class of cases of the employment of the word ‘meaning’ –though not for all – this word can be explained in this way: the meaning of a word is its use in the language.”

This notion makes meaning more about context and function. In the 1990s, the US philosopher Robert Brandom refined “use” to mean “inferential behaviour”, laying the groundwork for inferentialism.

Suppose a friend, or a curious child, were to ask us what it means to say “Tammy is a vixen”. How we would you answer them? Probably not by talking about categories of objects. We would more probably say it means, “Tammy is a female fox”.

More precisely, we would explain that from Tammy being vixen we may infer that she is female and that she is a fox. Conversely, if we knew both those facts about her, then we may indeed assert that she is a vixen. This is the inferentialist account of meaning; rather than assuming abstract categories of objects floating around the universe, we recognise that understanding is given by a rich web of relationship between elements of our language.

Consider controversial topics today, such as those around gender. We bypass those metaphysical questions blocking constructive discourse, such as about whether the categories of “male” or “female” are real in some sense. Such questions don’t make sense in the new logic because many people don’t believe “female” is necessarily one category with one true meaning.

As an inferentialist, given a proposition such as “Tammy is female”, one would only ask what one may infer from the statement: one person might draw conclusions about Tammy’s biological characteristics, another about her psychological makeup, while yet another might consider a completely different facet of her identity.

Inferentialism made concrete

So, inferentialism is an intriguing framework, but what does it mean to put it in practice? In a lecture in Stockholm in the 1980s, the German logician Peter Schroeder-Heister baptised a field, based on inferentialism, called “proof-theoretic semantics”.

In short, proof-theoretic semantics is inferentialism made concrete. This has seen substantial development in the last few years. While the results remain technical, they are revolutionising our understanding of logic and comprise a major advancement in our understanding of human and machine reasoning and discourse.

Large language models (LLMs), for example, work by guessing the next word in a sentence. Their guesses are informed only by the usual patterns of speech and by a long training programme comprising trial and error with rewards. Consequently, they “hallucinate”, meaning that they construct sentences that are formed by logical nonsense.

By leveraging inferentialism, we may be able to give them some understanding of the words they are using. For example, an LLM may hallucinate the historical fact: “The Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1945 between Germany and France after the second world war” because it sounds reasonable. But armed with inferential understanding, it could realise that “Treaty of Versaille” was after the first world war and 1918, not the second world war and 1945.

This could also come in handy when it comes to critical thinking and politics. By having a fit for purpose understanding of logical consequence, we may be able to automatically flag and catalogue nonsense arguments in newspapers and debates. For example, a politician may declare: “My opponent’s plan is terrible because they have a history of making bad decisions.”

A system equipped with a proper understanding of logical consequence would be able to flag that while it may be true that the opponent has a history of poor decisions, no actually justification has been given for what is wrong with their current plan.

By removing “true” and “false” from their pedestals we open the way for discernment in dialogue. It is based on these developments that we can claim that an argument – whether in the heated arena of political debate, during a spirited disagreement with friends, or within the world of scientific discourse – is logically valid.

Alexander V. Gheorghiu receives funding from University College London (UCL) and UK Research & Innovation (UKRI)

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.