It is another event from FA Cup history that is almost unimaginable now. The last moments of the 1979 final may have been deflating for Manchester United, but the homecoming was anything but. The team had come back from being 2-0 down as late as the 86th minute, to make it 2-2, only for Alan Sunderland to score a winner for Arsenal in the 89th. Not that you’d have guessed it from the scenes in Manchester.

“Even in ‘79, when we got back to the train station, we got an open-top bus to the city centre,” former United goalkeeper Gary Bailey says. “I think over 400,000 people lined the streets. It was incredible.”

For Liam Brady, the Arsenal playmaker who created Sunderland’s goal with a surging run, it went beyond that.

“It was one of the highlights of my career,” Brady says. “It was huge, and this was when everybody wanted to win it. Everybody was desperate to get there.”

It’s a sentiment that puts a different spin on some of the assessments of that era, that these Arsenal and United sides were mere “cup teams”.

These two were among the best of them. That famous “five-minute final” was the start of a period that showcased a traditional staple of the cup, as much a part of its lore as any upsets.

These were the sides never quite consistent enough to win the league, but could be as good as anyone on any given day. It meant they were often involved and victorious on FA Cup final day. That they all played with a verve and excitement – if also an erraticness – greatly added to their charm, and fitted with the folklore of the competition.

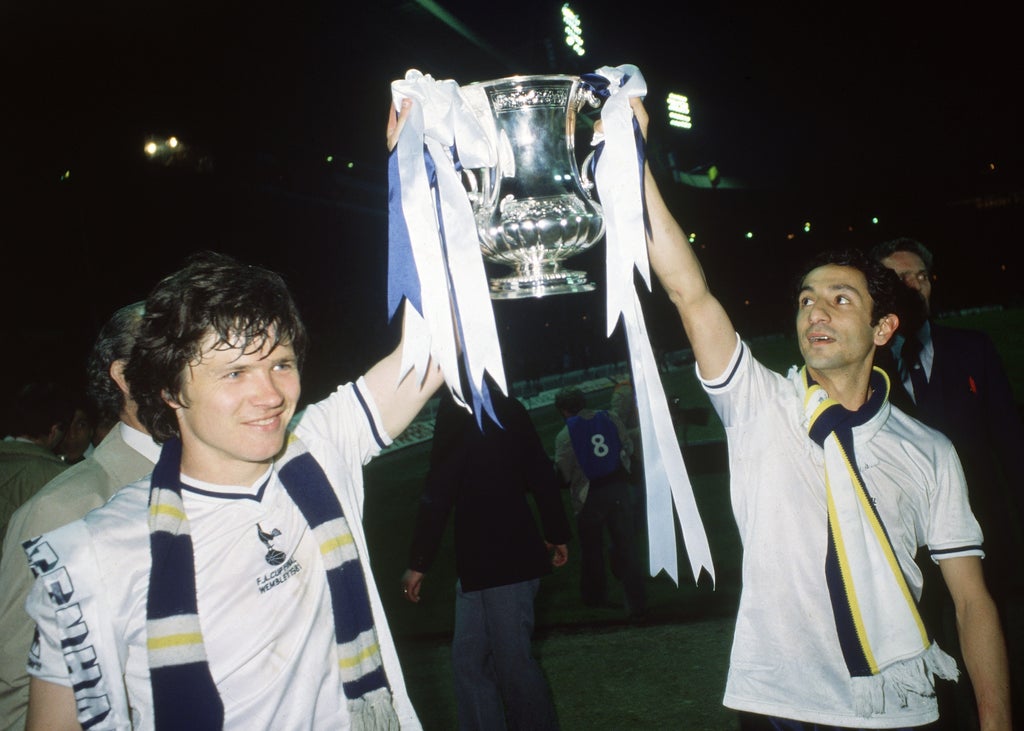

Among them were Bolton Wanderers 1922-29, who won three cups, with three-year intervals between them; Newcastle United 1950-55, who won three finals in five seasons; Arsenal 1977-80, for whom Brady played in three consecutive finals; Manchester United 1975-79 and then 1982-85, who appeared in six finals across two team cycles, winning three; and Tottenham Hotspur 1980-87, who won two of three finals, with Steve Perryman the victorious captain.

“When we won, it felt like a real major competition, it was coveted,” Perryman says. “When you tallied up what you’d done at the end of the season, you’d done your job if you’d won the FA Cup. You’d earned your money.”

Such qualifications point to some of the modern debates about the competition, not least whether Arsenal 2014-17 should be included in this group of great cup teams. What is certainly true is that none of the earlier managers would have dreamt of playing under-strength XIs throughout FA Cup seasons, as Arsene Wenger did even in those successful campaigns.

It was a different competition, which is why it’s arguable that the “cup team” has been another facet of cup mythology consigned to history.

This is what so stands out about Bailey’s memory of 1979. Some of these sides remain the most cherished in their clubs’ histories, even beyond some title winners. That's despite “only” winning competitions that just wouldn’t have the same currency for the big six today.

“We got to the final three times, and it was huge for us,” Brady explains. “If you say to people now you won the FA Cup, they think, ‘just the FA Cup?’ They don’t get what it used to be.”

It was so big that there was for a long time the argument that it was an equal feat to the league title, but just tested different qualities. That was the ability to rise to the occasion rather than grinding through wins.

“Our squad wasn’t strong enough to cope with the injuries and absences,” Perryman argues, “but on a one-off occasion… well, you’ve got to have something.”

Bailey elaborates: “Winning the league is the best measure of how good a team you are, but a very close second best was the FA Cup. And in some senses, it had even more glory than the league, which was a dour, hard nine-month battle.”

That do-or-die nature fitted with the swashbuckling football of some of these sides, and made them all the more memorable.

“The difference with cup football is that, unlike even in Europe, you don’t get a second chance. You’ve just got to go for it, and that’s what those matches were like. From the kick-off, it was just blood and guts, ball in the box, everyone going for it, total and utter excitement.

“It created legends. It was historic, whatever happened. You ask any United fan what they remember, in ’85, it’s Norman Whiteside curling it into the bottom corner [against Everton], the [1983] replay against Brighton, the dying moments when I had a save to make and then also ’79 when I didn’t get the cross from [Graham] Rix.

“These are enshrined in people’s memories.”

For Arsenal, it was Brady cutting through the United midfield before the Rix cross, in a moment that was the definition of a star seizing a game. For Newcastle, it was Jackie Milburn’s piledriver in 1951. For Spurs, it was Ricky Villa sending so many Manchester City players scattering.

It is telling, however, that some of the abiding memories for the players are cup ties against the regular league winners of the period: Liverpool.

Both United 1979’s run and Arsenal’s 1980 run involved epic semi-final series against the era’s benchmark club.

“People remember the finals, but some of the semis,” Bailey enthuses. “We beat Liverpool in a replay at Goodison Park in 1980 and in the 1985 semi-final, and I just remember the tension among the fans, players and management. Just getting to the final was a massive thing.”

The “Arsenal series”, which Bob Paisley titled the 1980 semi-final, entranced the nation for weeks.

“Liverpool in 1980 were the best team in the land but couldn’t beat us over four games in the cup,” Brady says. “We beat them 1-0 at Highfield Road on neutral ground and, in between the four of them, there was a fixture at Anfield in the league. We drew that one, they still couldn’t beat us. There was a capacity crowd at every game, it had a magic about it.

“We were a very good team on our day.”

The fact they did it on days, rather than over seasons, came to be held against these sides a little; as if they flattered to deceive.

“When you look at Liverpool, Ronnie Whelan and Sammy Lee were the engine of the team, that consistency to keep it going; that heart pumping,” Perryman says. “It’s not about me, but I had to keep changing positions to cope with gaps in our team.

“I think, to justify your existence, if you’re not doing it in the league, you’d better do it in the cup. That drove us on a bit, not that we didn’t believe we could be a league team. We flirted with it, but never quite did it.”

Certainly, such cup wins are no longer considered anything like, say, Chelsea’s Champions League successes of 2012 or 2020, or even Liverpool reaching the Kyiv final in 2018.

The stories made by the FA Cup, that cannot be made if someone is putting half a team out

As ever with the FA Cup now, such comments and comparisons point to a difference in the economic structure of the game rather than any great difference between these achievements.

Up until the late 1990s or so, clubs that had underwhelmed in the league would pour everything into the cup because that was where the glory lay but also – crucially – the money.

“A cup run made a hell of a lot of a difference to clubs, financially,” Brady explains. “There were bonuses that weren’t around in the league, the players were hyped up.”

“You always played your best team in the FA Cup,” Bailey adds. “You got the biggest crowds, with everyone excited this could be the cup run.”

What does that sound like?

“The Champions League is where the big money and prestige is. It’s where the players want to play.”

Now, big clubs that underwhelm in the league pour everything into the Champions League – or trying to get there. That’s where the glory lies but also more money than the game has ever seen. It has subsumed the idea of “the cup team” since it generally sees managers put out second-string sides in the FA Cup.

“Once the Champions League allowed four teams to qualify from the top leagues, the cup competitions were severely diminished,” Brady elaborates. “It’s a secondary consideration now even for clubs who have ambitions to get out of their division, to the point they’re not putting out full teams if challenging for promotion. Getting to the Premier League, or the Champions League, is much more important than the FA Cup. It’s diluted so, unless you’re safe, like a Leicester City, you’ll probably get the bottom and top sides not putting their best teams out.

“Manchester City can put out a second team and still get to the final. They might be playing second teams in the Championship.”

Most FA Cup victories now are just extensions of wider campaigns by Champions League clubs. They aren't so much cup teams as squads built for multiple fronts. That was even the case for all of Arsenal's last three under Wenger.

This leads to a sentence from Brady that is repeated word for word by Perryman. “The fans are being short-changed.”

“They’re supporting this image from the past, what the FA Cup meant,” Perryman adds. “The stories made by the FA Cup, that cannot be made if someone is putting half a team out.”

It means they’re certainly not putting out anything like the great cup teams. That is just something else from the competition’s history that's a little harder to imagine.