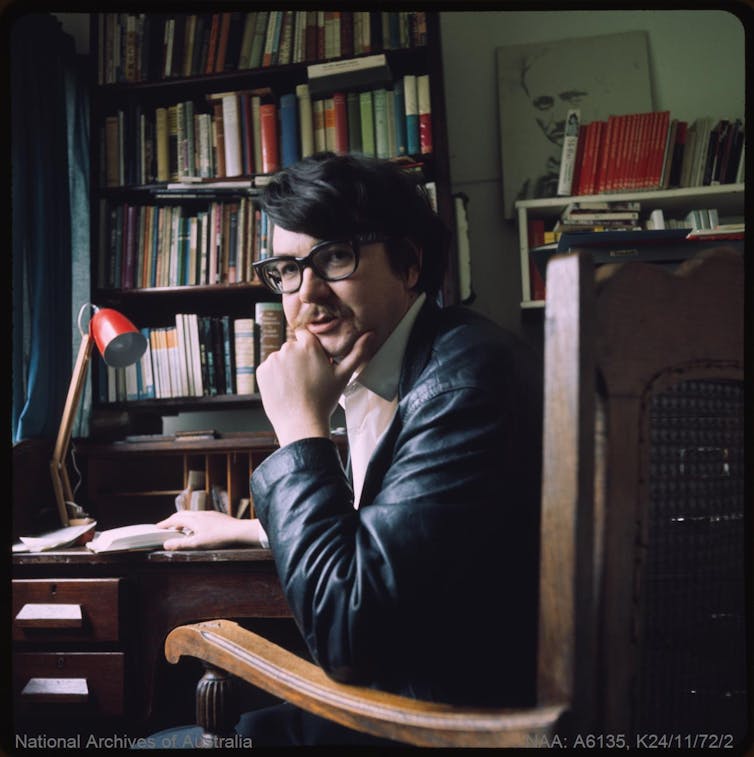

For Jack Hibberd, writing plays came from an “geographical accident”. As a young medical intern in the 1960s, he “fell in with the bohemian” Carlton Melbourne milieu that saw something in his poetry that suggested “monologues of a theatrical quality”.

These “bohemian” friends would later to go on to coalesce around La Mama and the Pram Factory with the Australian Performing Group, key incubators of Australian playwriting and a reminder that artists flourish in a supportive community.

In a self-effacing manner, Hibberd recounted his playwriting began from “theatrical ignorance”. He saw this approach as having “virtue”: he had “no preconceptions and leapt straight in”.

Hibberd, who has died at 84, will be remembered for his near 40 plays that would attract both national and international audiences – most notably, the first Chinese production of an Australian play with A Stretch of the Imagination (1987).

Finding the Australian voice

Hibberd’s first play Three old Friends (1967) was also the first production at La Mama. In a theatrical landscape dominated by scripts imported from England, Hibberd described the work as an “uninhibited use of Australian language”.

It is easy to forget the struggle for a post-war Australian culture to emerge from a British-centric domination. Playwriting would be key to the establishment and acceptance of a stage language of our own.

As Hibberd’s writing developed, British playwright Harold Pinter would be critical in inspiring Hibberd to focus on specific idiosyncratic dialogue. This would go hand in hand with Australian audiences lapping up hearing their own dialogue.

This was the New Wave of Australian theatre in the late 60s and early 70s. Hibberd and other local writers were exploring how we saw ourselves as Australian as against British.

The irony being, our writers were drawing on experimental European forms to re-create our own sense of Australianness.

Examining Australian cultural identity

Australian theatre historian Julian Meyrick notes Hibberd was the inheritor of Patrick White’s Expressionism, though more accurately able to acutely manage the dynamic between realism and anti-realism.

Hibberd’s A Stretch of the Imagination (1972), where the sole character Monk has no “being or self”, straddles this dichotomy situated in both an archetypal realist bush location and a deliberate bareness that reflects the setting of the absurdist tradition of Samuel Beckett.

Hibberd’s visualisation is similar to his use of dialogue: precise and economical. Hibberd begun writing this play with a visual concept: “I got into my noggin to see this oldish chap, very difficult chap, disgruntled contrary character with a rich life.”

This was a multi-faceted loner and exile who swung between a “typical Australian Larrikin to someone who claimed to have met Proust in Paris!”

Identity was fluid in this re-examination of an archetypal Australian cultural identity through intelligence and humour.

Bringing in the audience

His other landmark work, Dimboola (1969), concerns ritual and expresses Hibberd’s acute ear for the idiomatic quality of Australian regional dialect. The genesis began in London, where Hibberd was inspired from the audience participation in the experimental theatre he saw there.

As Hibberd recounts: “most of it didn’t work [and] it needed a structure, a form, a social ritual”. It became a wedding reception, the play being staged in halls made up to feel like a true reception, with the audience taking the place of the wedding guests.

In an interview, Hibberd crunched his fists together to explain:

It was a clash of clans. Two families trying to outdo each other: clothes, speech, social games or violence.

This was a sociological approach that again was sophisticated in its use of colloquial language. Hibberd chose the name Dimboola, a town in regional western Victoria, due to the “three flat stresses going across the mallee” revealing his dry and uncanny understanding of the subtext of language.

After its first production by the Pram Factory, many versions followed. The play had reportedly taken over $1 million at the box office by 1974. By 1978, it was estimated 350,000 people had seen it performed. It was made into a feature film in 1979, and launched an industry of dinner theatre productions in regional Australia.

For all its success, Hibberd considered a regional amateur production in Ararat the best because it was “bizarrely funny”.

His contemporary, Adrian Guthrie told me that, at the time, Hibberd’s work was “a phenomena with an acute sense of poetic language [via a] rich sophisticated Australian English”.

Writing until the end

His swansong, Killing Time, had its premiere just last year, appropriately at La Mama. Reviews said it brought forward the “inevitability of time” and death, but with still an “existential kick”.

Hibberd’s poetic voice, combined with experimental form, revolutionised Australian theatre and continued to inspire.

Dramaturg and director Tom Healey described Hibberd as

standing as an artist ranks with the likes of Boyd, Nolan, Hester and Tucker […] just as the Modernists dragged Australian painting firmly into the avant-garde, so the New Wave playwrights did the same for Australian theatre.

Hibberd will leave a powerful legacy through his contribution to Australian playwriting and culture.

Russell Fewster received funding from Adelaide Fringe/ArtSA and the Adelaide City Council for his recent production Two of Them that he wrote, directed and produced.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.