David Lynch was talking to me – at some length – about teeth. ‘I don’t know where it was I got so interested in teeth and dental instruments and drilling and the idea of drilling,’ the director – who has died aged 78, after being diagnosed with emphysema last summer – told me, ‘and then nerves, and different dimensions of a tooth, the roots…’

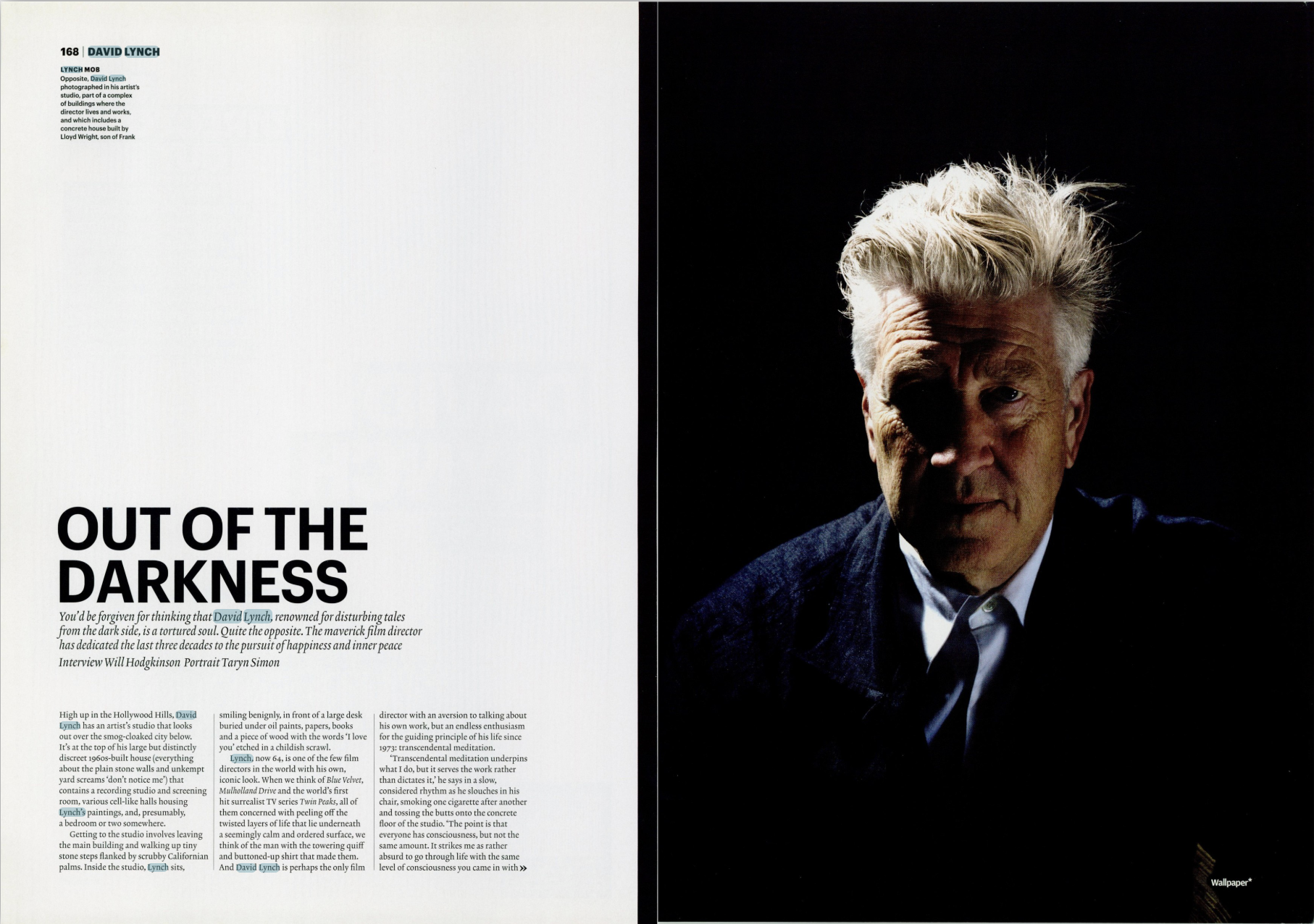

It was 2011. The previous year, the filmmaker had guest-edited the October 2010 issue of Wallpaper*. Lynch used the magazine as a platform to promote transcendental meditation, one of his myriad interests away from directing films – the latter something he hadn’t done since 2006’s Inland Empire. As it turned out, it was something he would never do again, although he would get behind the drama camera one more time, for 2017’s Twin Peaks, a long-awaited and suitably deliciously divisive, 18-episode third-season follow-up to his hallowed, hallucinatory early 1990s TV show and film. And he would appear in front of another director’s camera, in a secret cameo, as John Ford in Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans (2022).

‘Transcendental meditation underpins what I do, but it serves the work rather than dictates it,’ Lynch told interviewer Will Hodgkinson in a profile accompanying his gig at the mag. ‘The point is that everyone has consciousness but not the same amount. It strikes me as rather absurd to go through life with the same level of consciousness you came in with when there is a technique to expand it, and that technique is easy, effortless and supremely profound.‘

True to consciousness-stretching, truth-seeking form, Lynch also used his guest editorship to showcase a series of symbols that he’d illustrated – across a 16-page gatefold in the magazine – to, as we noted at the time, ‘represent unity in various religions and cultures’. There was, though, a full disclosure note from the editors, one acknowledging the sense-scrambling opaqueness that could attend Lynch’s work, in whatever medium: ‘Lynch uses a great deal of symbolism in his movies, but much of it is often lost on the average viewer, so, after an afternoon with our ancient texts, we attempt to explain what it all means…’

‘It strikes me as rather absurd to go through life with the same level of consciousness you came in with when there is a technique to expand it’

David Lynch

With creative and philosophical interests as horizon-wide as his, it was natural that Lynch repeatedly found a welcoming home in the pages of Wallpaper*. Also in 2010, we covered his exhibition ‘Darkened Room’, at Comme des Garçons' Six gallery in Osaka, at which the director paired 12 of his short films with a series of his paintings. Last year, Wallpaper* featured the installation ‘Interiors by David Lynch. A Thinking Room’ at Milan’s Salone del Mobile 2024, the director's debut at the furniture fair.

‘A few years earlier I presented Lynch the lifetime achievement award at the Rome Film Festival,’ explained Antonio Monda, the curator of the latter, ‘and when I visited him in Los Angeles I found him polishing a desk. I asked him, what are you doing? And he told me he designs furniture now,’ added Monda. ‘So when the Salone del Mobile invited me to commission a filmmaker for this special event, I knew he was the real deal.’

The surreal deal: that, too, was David Lynch. Born in Montana in 1946 and raised all over the US on account of his father’s work as a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture, he studied painting at Washington’s Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, Boston’s School of the Museum of Fine Arts and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. But in 1967, while studying in Philadelphia, he made his first short film, an experimental animation Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times). It would be untrue to say he never looked back – Lynch would repeatedly return to painting, and turn sideways to other visual forms – but filmmaking became a focus.

Three years later he moved to Los Angeles to study at the American Film Institute Conservatory. While there he began work on the film that would, eventually, become his debut feature, Eraserhead (1977). A bold body horror that he wrote, directed, produced, edited and scored, the low-budget flick became a beloved staple on the underground and late-night-movie circuits for years thereafter.

Eraserhead launched Lynch’s filmmaking career – but, true to what would become lifelong form, in a wildly unpredictable manner. His second film was The Elephant Man. A true story about Joseph Merrick, a severely disfigured man in Victorian London, starring an obviously unrecognisable John Hurt, on paper the surrealist black and white film was no one’s idea of a hit movie. Yet the 1980 feature was a critical and commercial smash, and earned eight Oscar nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actor.

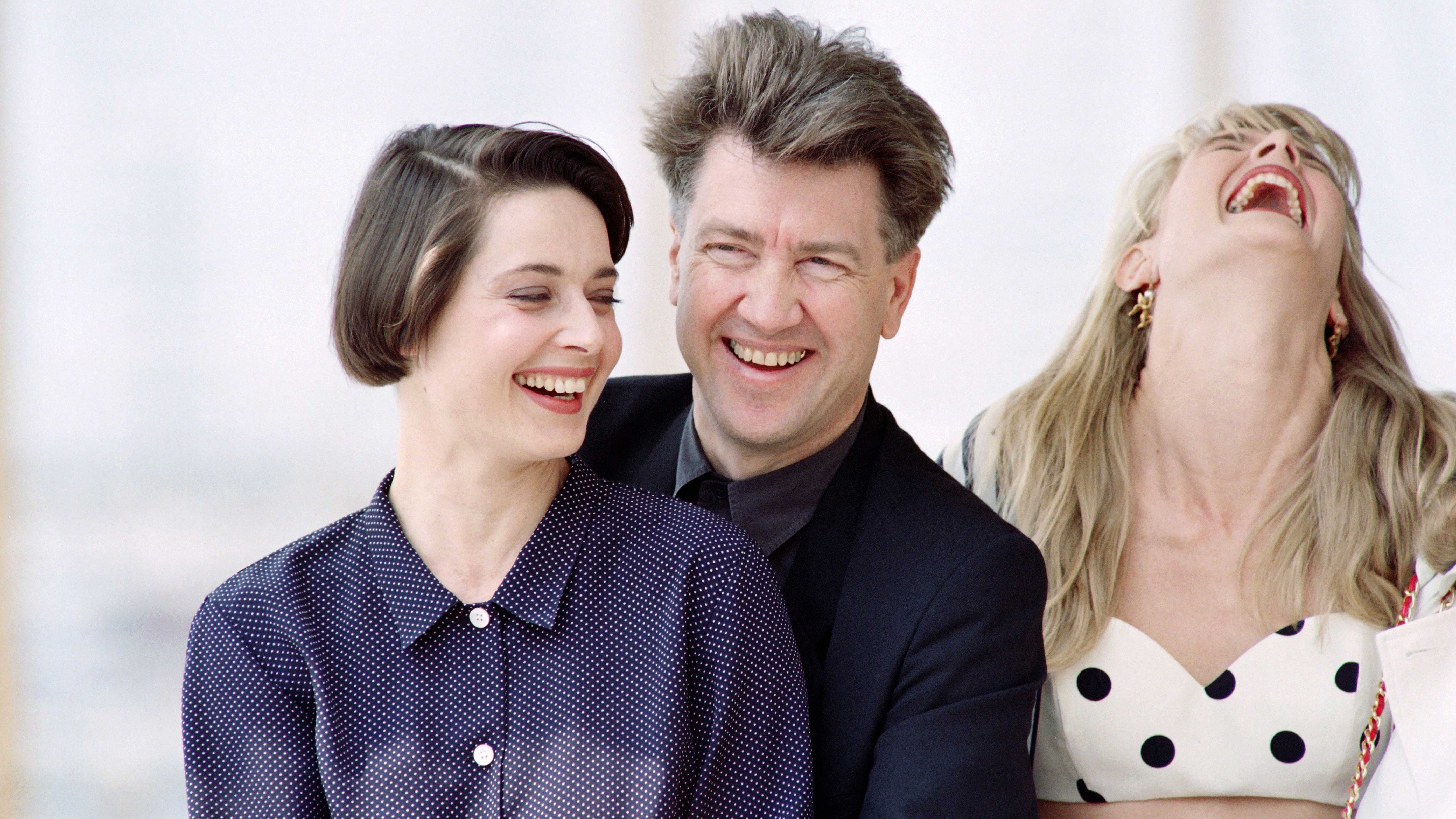

Then, another zig-zag: four decades ahead of Denis Villeneuve’s staggeringly more successful adaptation, the now-fabled misfire that was Lynch’s adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune (1984). But he more than atoned for Sting’s codpiece two years later with Blue Velvet. It was a neo-noir psychological thriller that set the ‘Lynchian’ non-template template and remains truly iconic on every level: the plot (the student, the femme fatale lounge singer and the psychopathic gangster…) the imagery (the ear! The gas-mask!), the casting (Kyle MacLachlan, Isabella Rossellini, Dennis Hopper, Laura Dern), the production design, the score, the titular theme song…

‘I hear Bobby Vinton’s version of “Blue Velvet”. And woah. I see night and green lawns. Red lips and a car. And I just start dreaming’

David Lynch

Talking to me 14 years ago, Lynch told me that, initially, he was no fan of ‘Blue Velvet’ in its original, 1951 incarnation, as sung by Tony Bennet. ‘I didn’t like that song! It was OK – but it wasn’t like rock’n’roll, it wasn’t something that drove me crazy. Then some years pass and I’m somewhere, and I hear Bobby Vinton’s version of “Blue Velvet”,’ he says of the now-definitive 1963 take. ‘And woah. I see night and green lawns. Red lips and a car. And I just start dreaming. That started the whole thing.‘

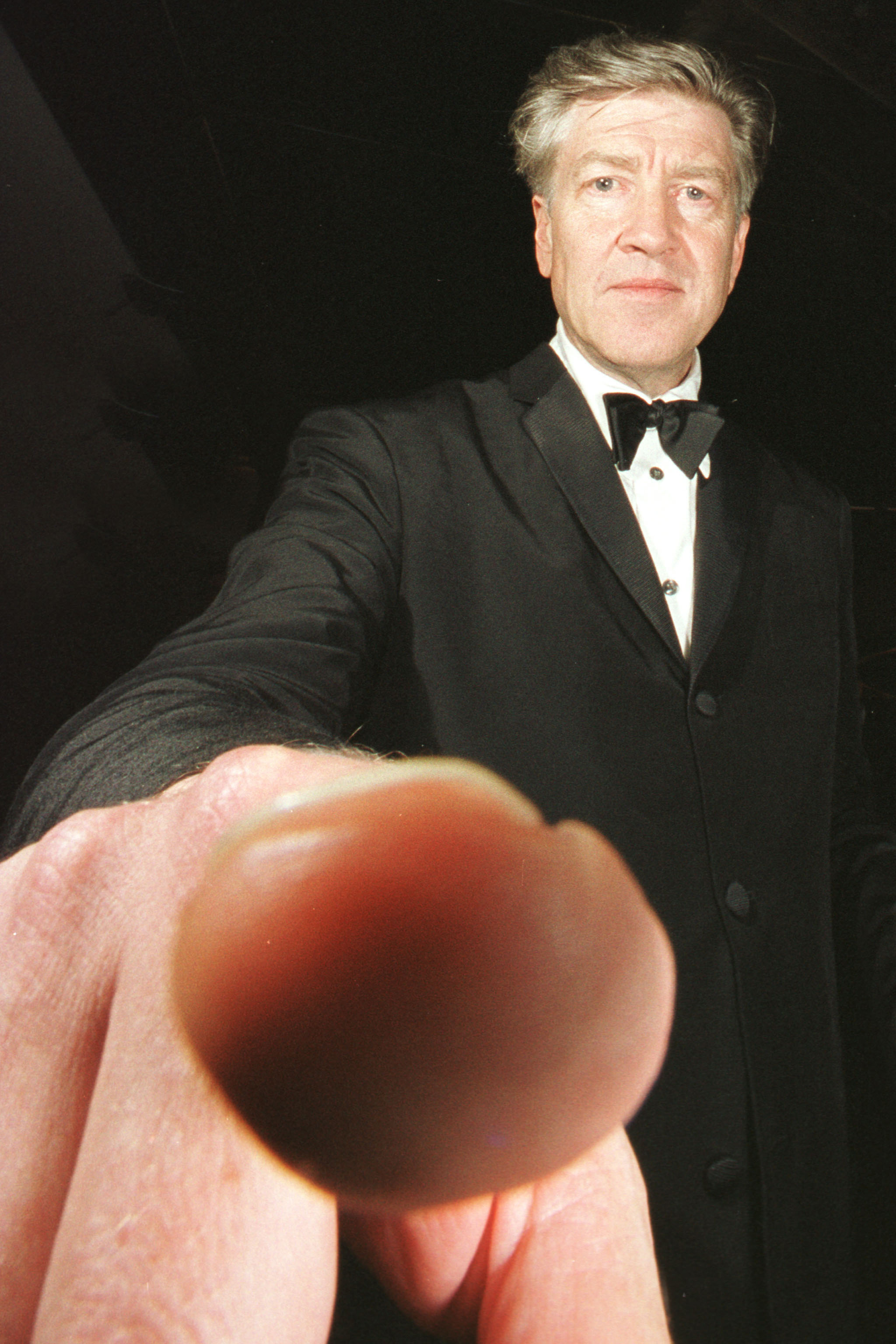

Music, then, was the inciting force for the movie that remains, arguably, the cornerstone of a filmography that would ultimately see Lynch awarded the Venice Film Festival’s 2006 Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement and an Honorary Academy Award (2019). It was also the reason I was invited into his LA home in 2011.

That morning, we sat in the concrete cube that was this multidisciplinary artist’s painting studio, one of a series of similar structures slotted into the Hollywood Hills that comprised his home with his fourth wife, the actress Emily Stofle. We were, of course, drinking coffee. And yes, it was damn fine, not least because it was a cup of David Lynch Signature Cup Organic House Roast (signature notes, according to my genial and welcoming barista from beneath a shock of silver quiff, ‘sweetness, smoothness, no bitterness even if it’s just pure, straight black espresso, packed with flavour’).

But we were talking, at length, about teeth.

‘I love the shape of a tooth, when you pull ’em out,’ Lynch continued in something like a Proustian reverie. ‘They’re little hard rocks that grow uniquely next to something soft, the tongue. I mean!’ he exclaimed excitably, ‘it’s incredible!’ The reasons for his interest in matters dental stretched backwards and forwards. Firstly, he was recalling an image of a facially disfigured man, taken from a book called Dental Hygiene, Dental Applications and Oral Pathology, and repurposed for the cover of the script for his 1997 film Lost Highway. Secondly, he was musing on the lyrical inspiration for a track on what was another whiplash left-turn for a filmmaker revered for a career-long dedication to travelling down his own lost highway.

At the age of 65, Lynch had made a dance(ish) album. Certainly, it had a title – Crazy Clown Time – that readily suggested another twisted celluloid fever dream, one that fitted David Foster Wallace’s definition of ‘Lynchian’: ‘A particular kind of irony where the very macabre and the very mundane combine in such a way as to reveal the former’s perpetual containment within the latter.’ This, after all, was an auteur revered for movies – his perfectly imperfect ten-strong filmography also includes Wild at Heart, The Straight Story and Mulholland Drive – reliably underpinned by an implicit Director’s Message: ‘Are you sitting uncomfortably?’

But Crazy Clown Time was no gothic horrorshow. It was being released on Sunday Best, the UK dance label co-founded by DJ Rob Da Bank. The first single, ‘Good Day Today’, was already receiving love in the clubs of Ibiza. Lynch was taking part in a conversation for that year’s International Music Summit, an annual electronic music culture conference held on the White Isle. That said: the song on the album that seemed to interest him most was no dancefloor-igniting banger. ‘Strange and Unproductive Thinking’ was a seven-a-half-minute ambient track with a throbbing rhythm and vocals from Lynch, a spoken-word lecture delivered via vocoder: ‘Teeth, while not necessarily considered one of the primary building blocks of happiness, can in fact become a small sore, festering and transferring negative energies to the once quiet and peaceful mind.’ Altogether now: ‘The hideous odours emitted from the oral cavity…’ Put your hands in the air like you don’t care!

This, in 2011, was where David Lynch found himself, and happily so: making genre-blurring music, promoting transcendental meditation, painting canvases and musing wildly. Still, though, I wondered: why hadn’t he made a movie since Inland Empire five years previously? His reply came swiftly. ‘I haven’t got an idea that thrills my soul to go and do it. And that still remains the case. Also… say the film industry is a hot-rod car. And it was going about 120 miles an hour, straight down a road. But about five or seven years ago, it hit a little bump. And for some reason skipped over into the gravel. And it’s been in bushes-flying spin [ever since], and it hasn’t stopped yet.’ Lynch sipped his coffee, smiled and shrugged. ‘So that’s the way I feel.’ It would, ultimately – and, for cineastes, tragically – remain the way he felt.