One Saturday late last summer, Boca Chica Beach was cloudy and oppressively humid. An incoming thunderstorm stretched from Matamoros to Brownsville several miles away, which I could see over the flat Tamaulipan thornscrub, just past the duneline and SpaceX’s launch towers.

Thunder intermittently interrupted the sound of crashing waves, but the storm was otherwise not threatening those gathered here. This group, made up of local organizers and Rio Grande Valley residents, was intent on being at Boca Chica Beach—at Texas’ southernmost tip, across the ship channel from touristy South Padre Island—then and into the future.

ENTRE, a community archive and film center based in Harlingen, hosted the gathering to help people learn more about Boca Chica Beach. Under a handful of canopies were plastic tables and chairs, coolers, and several people talking about the beach sprawling before us.

This event, “Playa de Memorias,” was an extension of ENTRE’s archival project called Boca Chica, Corazón Grande. For the past three years, ENTRE has collected photos, home movies, and oral histories of Boca Chica from Valley residents, who’ve visited the free-access beach, little-known to tourists from the rest of the state, for generations to fish, barbecue, and even camp overnight. On this day, people were welcomed to make their own memories and appreciate the Valley’s past, present, and future.

Children played as the adults—organizers, journalists, and artists—traded stories. Against the dunes, chef and anthropologist Luna Vela, alongside chefs Nadia Casaperalta and Mia Eustaquio, served food including flounder ceviche with heirloom corn tostadas and wave-patterned quesadillas with nopales, both odes to the foodways of the people who lived here long before the place had a European name.

Along with offering nourishment after hours spent in the sun and gulf, the dishes were made with the idea in mind that everything tastes better on the beach. “I’m just trying to feed that magic, feed that feeling,” Vela told me.

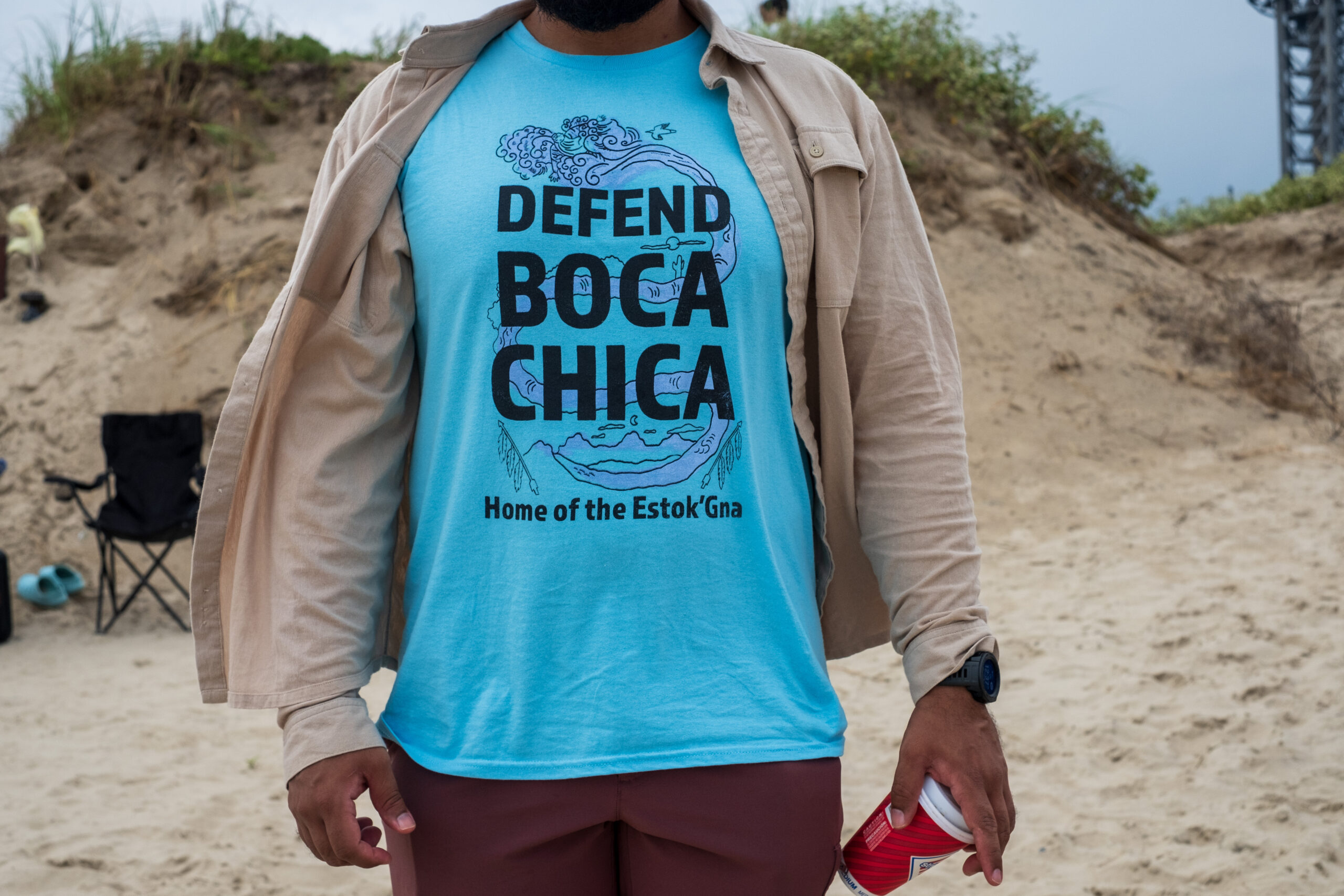

Among the group were organizers who’ve spent years fighting against the encroachment of Elon Musk’s SpaceX launchpad, which looms over Boca Chica, and the hulking production facility up the road. Local officials have ignored their outcry, including over excessive closures of the only road leading to the beach, so this group is trying to raise awareness in the Valley.

The hope is that the more people who see Boca Chica Beach and feel its connection to the Valley’s collective memory, the more likely it will be saved from further development. The effort is especially pertinent as SpaceX plans to launch its massive Starship rocket up to 25 times a year and add more buildings—and as Musk looks set to receive special treatment from a second Donald Trump administration.

“There is also this desire to show that regardless of how you feel about SpaceX, there is no doubt that Boca Chica is changing because of its development,” Monica Sosa, the project curatorial manager for ENTRE’s Boca Chica, Corazón Grande, said. “If this entity is continuing to ask for an increase in rocket launches, we are not going to have this [beach] anymore as it is right now.”

As Boca Chica, Corazón Grande is a preservation project for images of Boca Chica, it too is one for the people fighting for it. Years of advocacy have burnt out many organizers met with indifference by local leadership. They and other locals are grieving for what Boca Chica Beach and Brownsville were before SpaceX, Sosa said.

Destruction isn’t always something physical, but also something done to memory. Without looking at photos, home movies, and listening to stories, it’s hard to remember what Boca Chica was before SpaceX came to town about a decade ago and expanded, especially since 2018.

“It is a preservation project across the board,” Sosa said. “But it’s also an active project on self-preservation for us as community members.”

People are still coming to Boca Chica Beach, even as SpaceX’s footprint grows seemingly by the day, its reach along Highway 4 ever expanding. SpaceX’s ability to have the beach closed on Labor Day is restricted, and people take advantage.

The storm eventually made its way to the gathering but only for a few moments. The drizzle dissipated, and the clouds rounded around the launch towers. Everyone carried on, reenergized by a cool wind and the Gulf oysters now being served.

Growing up in nearby Port Isabel, I visited this beach frequently when I was younger, as did my father’s family long before I was alive. I only vaguely remember what it looked like before the towers and before the noise. When I look out at the gulf, surrounded by those who’ve tried mostly in vain to protect this place, I recall those memories more easily.