A young Indian physicist was under pressure. His heart was set on working in the field of general relativity – the study of space, time, and gravity. But the director of his institute stood in the way. The physicist was told that he had to work on a field of the director’s choosing, or leave. He still kept at it, working on the mysteries of gravity in his spare time.

He ended up writing the most significant paper on general relativity to have come out of India.

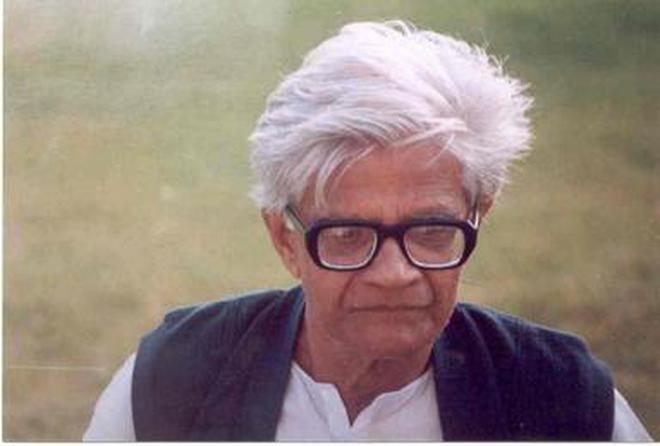

This young physicist was Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri. The central result of his paper, published in 1955, is now known as the Raychaudhuri equation. It was important to the work of Stephen Hawking, Roger Penrose, and others – work that revolutionised general relativity.

This year is Raychaudhuri’s birth centenary.

A breakdown in the theory

Raychaudhuri was born in Barisal (now in Bangladesh) in 1923 and educated in Kolkata. After completing his MSc in physics from Science College, he joined the Indian Association of Cultivation of Science (IACS) to pursue experimental physics research.

While the work didn’t suit him and he eventually dropped out, he discovered in the IACS library his deep interest in general relativity.

Albert Einstein had developed the theory of general relativity in 1916, seven years before Raychaudhuri was born. Before Einstein, gravity was believed to be a force that attracted massive objects towards each other. But general relativity explained gravity to be the result of massive objects bending the fabric of space and time around them.

The theory had a problem, however. It predicted that at certain points in space and time, gravity could become infinitely strong. In other words, space and time could become infinitely curved. All matter in the vicinity would get pulled in and converge at those points. Such points are called singularities, and that the theory allowed for them signalled a breakdown of the theory itself.

A barrier

In Raychaudhuri’s time, it was an open problem as to whether the singularities were bugs introduced by the unrealistic simplicity of the models – or features of reality itself. The question was unsolved because realistic models of the universe were notoriously difficult to solve mathematically.

Raychaudhuri was looking for the answer. Working as a scientific officer in IACS, a position well below a faculty member, he dove into the topic – and immediately hit a snag in the form of the director of the institution, Meghnad Saha.

Saha is one of the greatest Indian scientists in history. But as director, he could be a micromanager. He deemed general relativity to be too impractical a topic to work on. He told Raychaudhuri to work either on more ‘useful’ topics or find another job. With few career options available to him, Raychaudhuri had no choice but to comply.

But he did not give up on gravity. Even as he worked on the topics chosen for him by Saha, Raychaudhuri pursued the problem of singularities in his spare time. Soon, he hit on a highly original approach that entirely bypassed the mathematical challenges.

The north-bound ships

According to general relativity, every bit of matter tries to move in a straight line in space and time. But space and time are themselves bent by massive objects.

As an analogy to how matter moves in a curved spacetime, consider a couple of ships that start sailing in parallel. Both the ships travel north. Even if they sail in the straightest possible line, following their bows, they will end up converging at the North Pole. To someone who is not aware (or, more likely, in denial) of the shape of the earth, it would look like the ships had been pulled together.

Similarly, when a passing asteroid gets sucked into the earth’s atmosphere, it is because the earth’s mass has warped the fabric of spacetime around it. The straightest possible path in this curved fabric leads directly to earth.

Raychaudhuri studied the motion of bits of matter navigating the fabric of spacetime. Each bit followed the straightest path in space-time. He found that, just like the north-bound ships, the bits of matter were bound to converge to a single point as long as they had positive energy.

More accurately, he considered that the bits were initially spread across a volume and asked how this volume would change as each bit tried to travel straight in a curved space. Raychaudhuri found that the answer was given by a simple, elegant formula that showed the volume would always decrease regardless of how curved the spacetime was. This is the celebrated Raychaudhuri equation.

More powerful than imagined

The equation dispensed with the need to find realistic solutions by indicating, strongly, that singularities were inevitable in the general theory of relativity. However, it was not a complete proof, because while all singularities are points where matter converges, all points of convergence are not singularities.

For a complete proof, one had to show that there were no points of convergence that also were not singularities. Such a proof was developed in a series of theorems, chiefly by British physicists Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking. The Raychaudhuri equation played a key role in many of them. It was also central to Hawking’s famous area theorem, which proved that the surface area of a black hole never decreases.

The Raychaudhuri equation proved to be more powerful than Raychaudhuri himself may have anticipated. However, he found little appreciation in India until his work received recognition in the West, and even then it didn’t transform his career. IACS members scuttled his promotion to the faculty while Calcutta University rejected his application. Raychaudhuri eventually joined Presidency College, Kolkata, where he became a legendary teacher, inspiring generations of future physicists.

Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri’s story teaches us the folly of telling scientists what to work on and the importance of following one’s own path under difficult conditions. For many Indian scientists, his story continues to both resonate and inspire.

- The central result of Amal Kumar Raychaudhuri’s paper, published in 1955, is now known as the Raychaudhuri equation. It was important to the work of Stephen Hawking, Roger Penrose, and others – work that revolutionised general relativity.

- In Raychaudhuri’s time, it was an open problem as to whether the singularities were bugs introduced by the unrealistic simplicity of the models – or features of reality itself. The question was unsolved because realistic models of the universe were notoriously difficult to solve mathematically.

- Raychaudhuri studied the motion of bits of matter navigating the fabric of spacetime. Each bit followed the straightest path in space-time. He found that, just like the north-bound ships, the bits of matter were bound to converge to a single point as long as they had positive energy.

Nirmalya Kajuri is an assistant professor of physics in IIT Mandi.