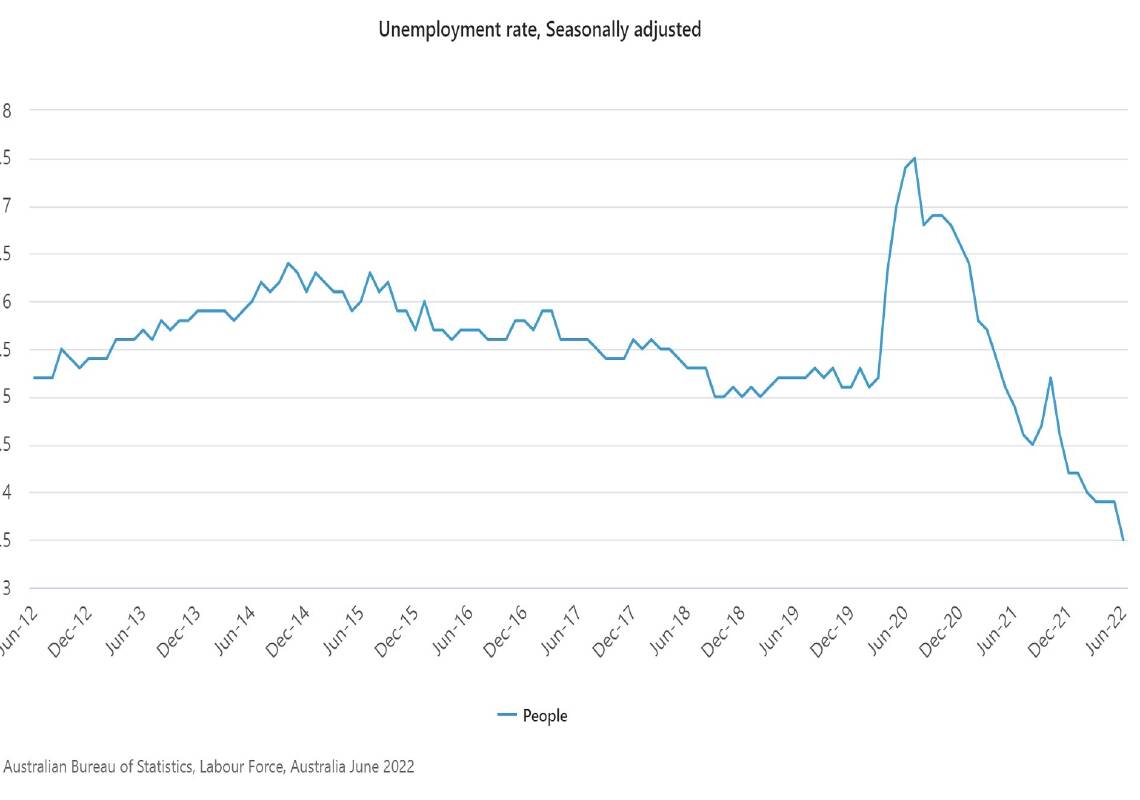

AUSTRALIA'S official unemployment rate of 3.5 per cent is the lowest in almost half a century.

In Newcastle and Lake Macquarie, the jobless rate is an even better 3 per cent, rising to 4.5 per cent elsewhere in the Hunter.

Not so long ago, mainstream economic theory regarded a 5 per cent jobless rate as "full" employment.

We can quibble about the actual numbers, because it takes just one paid hour of work a week for the ABS to consider a person "employed".

Many would question that definition, but as long as the definition remains constant, the trend still counts.

After years of 5 per cent to 6 per cent unemployment, the rate flew north with COVID to an official 7.5 per cent in July 2020.

Two years later, it has more than halved to the June figure of 3.5 per cent.

At first glance, such a low unemployment rate is something to celebrate.

Enforced unemployment can be soul-destroying, as well as financially debilitating, so few people would argue against the benefits to participants of a strong jobs market.

But looking more broadly, the record low jobless rate is at least partly the result of an "artificial" labour shortage caused by COVID-driven barriers to job-seeking immigrants.

At the same time, we are witnessing the long-expected reappearance of monetary inflation, with the attendant risk of a wages spiral if employers are obliged to lift pay to attract and retain the workers, when job vacancies far outnumber the people available to fill them.

Faced with a loss of economic stability, interest rates are the primary lever used to control the speed of our free-market economies.

Unfortunately, they also add to household mortgage stress, and they almost always push up the jobless rate.

Last month, US Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell told lawmakers that while rate increases were "designed to drive growth down ... to give ... supply ... a chance to catch up", they carried "a risk that unemployment will move up".

This week, Reserve Bank of Australia chair Philip Lowe admitted inflation was "much higher than we had earlier expected", with "powerful global factors" driving inflation higher "everywhere".

But while eroding savings, inflation also eases the burden on borrowers, something that indebted governments everywhere will be quietly considering.

ISSUE: 39,928

RELATED READING: John Tierney's weekly column, on 'the inflation genie'