First Nations people please be advised this article speaks of racially discriminating moments in history, including the distress and death of First Nations people.

It was a sudden and unexpected announcement. Late last week, the chairman of the Australian War Memorial, Brendan Nelson, declared the governing council had decided to develop a

much broader, a much deeper depiction and presentation of the violence committed against Indigenous people, initially by British, then by pastoralists, then by police, and then by Aboriginal militia.

The statement was made in the presence of the Minister for Veterans’ Affairs Matt Keogh who has administrative responsibility for the memorial. Keogh observed that the current $550 million expansion of the institution would allow for a greater recognition of the frontier wars. He added

the recognition and reflection on frontier conflict is a responsibility for all our cultural institutions, not just here at the war memorial.

Minister for Indigenous Australians Linda Burney remarked that her government was committed to a truth telling process about Australian colonial history “and a failure to see that reflected in this key institution would be jarringly out of step with this new phase of national reckoning”.

The memorial’s resistance to acknowledging the frontier wars that occurred here over 140 years had seemed implacable.

Reference was always made to official regulations confining its attention to Australian-raised forces fighting overseas. Suggestions for minor amendments to the relevant act were brushed aside, leaving the inescapable impression that the memorial’s board was simply not interested in the untidy, irregular warfare witnessed all over the continent.

The constant riposte to criticism was that while frontier conflict was real enough it should be commemorated in the National Museum.

A board on notice

Some scepticism has followed the sudden conversion. Long-term critics of the memorial wonder if it is anything more than window dressing or whether the present administration has the required knowledge and skills to respond appropriately to such a significant national task.

But a public commitment made with strong official approval cannot easily be reversed. And it is not a mission outside observers will lose interest in. The whole board (which includes ex-PM Tony Abbott) must know they are now on notice. And the memorial is probably the only national institution that has the resources at the moment and, likely, in the near future, to get the project underway.

The times are propitious as well. There is now widespread acceptance of the reality of frontier wars far more so than during the “history wars” of 20 years ago.

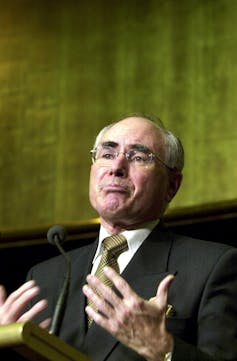

There are few contemporary political leaders who would share John Howard’s personal hostility to the “black armband view” of history. A survey conducted by Reconciliation Australia found 64% of their sample accepted the reality of the frontier wars, 6% didn’t while 30% were unsure.

A new generation of historical research has provided powerful confirmation of the extent and duration of the “killing times” particularly during the conquest of north Australia in the second half of the 19th century. The work of Lyndall Ryan and her team at the University of Newcastle has mapped massacre sites all over the continent.

Read more: In The Australian Wars, Rachel Perkins dispenses with the myth Aboriginal people didn't fight back

More than 60,000 Aboriginal deaths?

Extensive new research in Queensland, concentrating on the Native Mounted Police, has raised the possibility the Aboriginal death toll may have been well over 60,000. This would push casualties in the frontier wars to a figure rivalling the total loss of Australian lives in the first world war.

The most innovative development in the relevant scholarship is to focus on Aboriginal resistance in its many forms, not to concentrate only on their fate as victims.

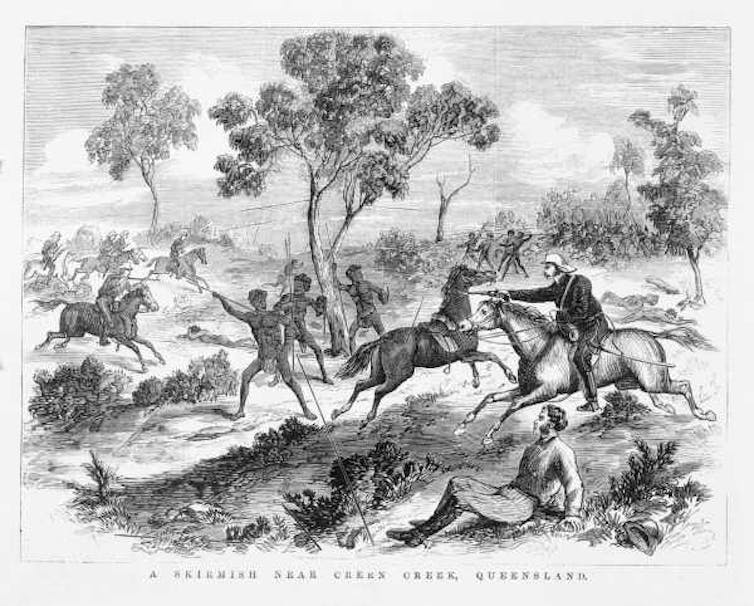

Warriors such as the father and son, Moppy and Multuggerah, who in 1843 mounted an ambush of a frontier expedition carrying supplies from Brisbane to the Darling Downs. Or the Wiradyuri war of resistance in an around Bathurst in 1822-24, led by Windradyne, and others such as Blucher and Jingler.

Or the Anaiwan people of New South Wales who strongly resisted the expansion of 19th century pastoral settlement on the New England tableland. Or the Tasmanian resistance fighter Tongerlongeter.

This scholarship will benefit from the assistance of the memorial to further explore how the warriors conducted their campaigns. We need to know how these warriors made use of specific geographical characteristics of their homelands; how they exploited their superior knowledge of country; how they sought to counter the greater firepower of the invaders.

Above all we need to be able to explain how they were able to avoid endless attempts by European soldiers to bring on an open confrontation.

Read more: Friday essay: Tongerlongeter — the Tasmanian resistance fighter we should remember as a war hero

In his statement, Brendan Nelson spoke of the violence committed against the Aboriginal people but it is most important that the memorial is now able to investigate the Aboriginal resistance, and see it as a military operation.

We need to find out if tactical skills were widely discussed and passed on from nation to nation. And then there is the question of how different groups sought to come to terms with the white men who had settled down in their country and how such local agreements or “treaties” were negotiated, as they were everywhere sooner or later.

Beyond this vital research, how might the memorial tangibly present these engagements to Australians? We don’t have the names of most of the Aboriginal dead. We do have those of the Europeans who died at their hands. Should they be acknowledged? (In the early years, most were convicts).

The most significant symbolic act would be placing a tomb for the unknown warrior next to the grave of the unknown soldier. Those who fought for empire would be at rest with those who fought against the empire.

Contextualising empire

Memorial staff could also relate the Australian experience to the rest of the world and in particular, to the resistance by Indigenous people in many of the European empires.

The memorial is well placed to explain the rapid evolution of the weapons available to the settlers and how the availability of long range and accurate repeating rifles in the final decades of the 19th century completely changed the balance of power all along the frontier. But this was part of the global story of the rapid expansion of the European empires in the decades leading up to 1914.

Many studies have examined what, in the 19th century were known as small wars, fought between tribal people and Imperial military forces. They often provide valuable insights to how Australia’s frontier wars unfolded.

The classical tactic used by the Europeans to put down rebellion elsewhere was to organise punitive expeditions which could operate from land or sea. It frequently proved difficult to find the elusive enemies but the next best tactic was to destroy villages, burn crops, kill or run off domesticated animals and even poison wells.

None of these stratagems were available in Australia, given the lack of permanent villages or other stationary assets, which explains in part why the British resorted to punitive massacres – from the foundation years at Sydney Cove until the Coniston massacre of 1928.

Henry Reynolds does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.