Although I’m not proud of it, as an author, I often engage in the masochistic ritual of checking my Amazon ranking and reviews.

So back in the spring, shortly after my latest book came out, I typed “The Puzzler” by A. J. Jacobs into the Amazon search bar and pressed “Enter.”

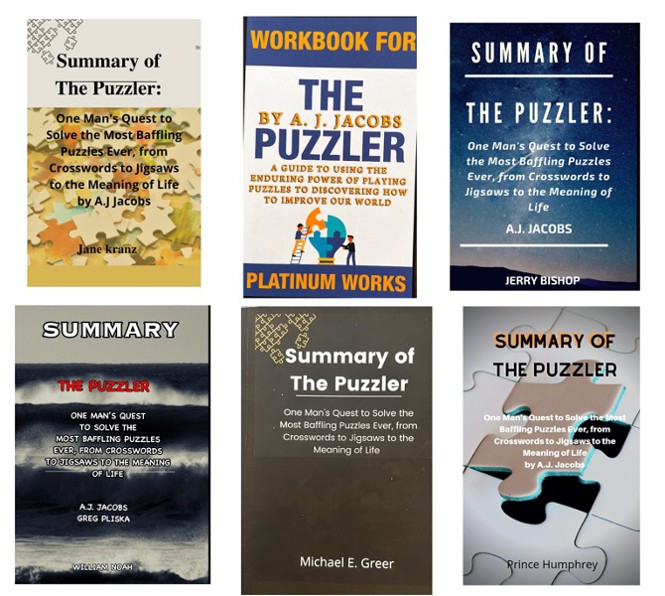

Up came my book, of course. But to my surprise, so did several other books. Six of them. These books had titles such as Summary of The Puzzler by A.J. Jacobs and Workbook for The Puzzler by A.J. Jacobs. They ranged from $5 to $13.

As you can imagine, I was a bit baffled. I know firsthand the long history of study guides and book summaries. In high school, I used Cliffs Notes to help me decipher The Scarlet Letter, and its rival SparkNotes is a huge business.

But my book—a memoir and cultural history about puzzles, including crosswords, jigsaws, and riddles—had come out just a couple of weeks before. And though I was proud of it, it wasn’t yet a classic text being taught in schools and dissected in doctoral theses.

Naturally, I ordered all of the guides and workbooks to The Puzzler by A.J. Jacobs—four paperbacks and two Kindle ebooks. A few days later, I settled down in my Aeron Chair to read the summaries of my own book.

The first thing I noticed is that they are remarkably slight. They’re all pamphlet-size books with a font huge enough to rival that of The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The longest runs 49 pages, and one summary by somebody named Prince Humphrey clocks in at a mere nine pages. That’s some efficient summarizing!

The covers of the summaries vary in theme. Four of them have clip art of jigsaw puzzles, which seems fine, if uninspired. But the summary by Jerry Bishop features a cover image of a night sky with a shooting star, and another has ocean waves. Because the universe and the ocean are puzzles, I guess?

I randomly selected William Noah’s summary and began to read. It opens: “This is a book of fun.” Well, that’s nice. I do think my book is a book of fun. I noticed that a lot of the sentences are like this—slightly ungrammatical, as though they were written by someone who learned English late in life. Another of the summaries begins: “The George Plimpton of thinking exercises takes readers on a crossword, maze, and beyond the journey.”

Wait. I recognized that. It’s a slightly altered version of a sentence in the Kirkus review of my book. The more I read, the more I started to realize that the summaries’ passages are lifted from other sources. The text is a hodgepodge, a mélange of snippets from book reviews, my book’s jacket, magazine features, and passages copied directly from my book.

Not to mention, the cut-and-paste job is kind of lazy. The segues are jarring, and many of the summaries are repetitive, with identical passages popping up on the same page, giving several of them an “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy” vibe.

Many of the summaries are similar. Not identical, mind you, but they use a lot of the same reviews and articles. Perhaps the summarizers went to the same summarizing school?

To their credit, the summarizers don’t always reprint passages verbatim. They can be handy with a thesaurus. A summarizer named Jane kranz (the k is lowercase, perhaps a nod to bell hooks or e. e. cummings) wrote that my book is “a bucket of monkeys’ worth of puzzle-solving fun.” Hmm. Kirkus called my book “a barrel of monkeys’ worth of fun for the puzzle addict in the household.”

Sometimes, I learned new things about myself. In Jerry Bishop’s summary, he writes, “Jacobs quit attending classes two months before he graduated college and began completing crossword puzzles.” I don’t remember doing this. Later, I realized that this detail was taken from The New York Times review of my book, where the reviewer—Judith Newman—talked about skipping classes. Bishop had conflated me and the reviewer.

Perhaps the worst part: Several of the summarizers seem to have gotten bored of summarizing my book by the middle. Or not even the middle. Greer summarizes two chapters. I wrote 18, but there’s no mention of the last 16.

Though most are similar, one of the books is radically different: Workbook for The Puzzler, credited to Platinum Works. What is a “workbook”? Well, in this case, it’s a book with a lot of blank pages for the reader to fill in, labeled “Notes,” “Personal Notes,” and my favorite, “Other Things.”

The workbook’s non-blank pages contain text about puzzles—and refreshingly, the text isn’t taken directly from my book or reviews of it. Rather, the workbook is a collection of tips on solving puzzles. And they’re solid tips, too, such as “Don’t pressurize yourself too much,” which seems good for both puzzles and scuba diving.

It took me about an hour to read through all of my summaries and workbooks. At the end, I felt a mix of emotions.

First, I was flattered that these folks, whoever they are, had bothered to rip off my book. But I was also pissed. I was angry on behalf of any and all unsuspecting readers who had ordered a workbook, only to receive these worthless word salads. And I was, of course, annoyed that they might cut into my book sales.

But the anger was tempered by my amusement at how absurd these works are, how jarring the segues, how creative the grammar—like a Yoko Ono poem. Plus, it was kind of a fun game—yes, even a puzzle!—to figure out the origin of the passages.

I also felt shame, because I knew I was part of the problem. People like me have led to this cottage industry. I’m a sucker for Summary Culture. Sometimes I’ll watch authors’ TED Talks instead of buying their book. Or I’ll listen to this app called Blink that condenses books to a few minutes of audio. Or I’ll read a Wikipedia summary of an author’s ideas. It’s not good. I know I’m missing nuances and also undermining the very industry I work in, but over the past 10 years, I’ve bought into the cult of efficiency. I think it’s because there’s just so much information out there, and I feel social-media pressure to keep up. Maybe the ridiculousness of these summaries will finally embarrass me into reading full books again. Maybe.

Another reaction? Fear. These summaries are amateurish and incomplete. But in a couple of years, will artificial intelligence be able to whip up useful and well-written summaries of nonfiction books? Will anyone buy the actual book?

Finally, I was curious. That’s the theme of my book, curiosity. Who is putting out these books? Is it a team of people? One person? An AI robot?

I embarked on an investigation. The QR codes on the back of the books didn’t work, an immediate dead end. The Amazon pages and the Google results of the authors didn’t yield much either.

I discovered that Jane kranz—who does bother to capitalize her last name on many titles—is perhaps the most prolific of the summarizers, having published summaries of at least a dozen other books, including a biography of the pro golfer Phil Mickelson and the memoir of the scarf-wearing Trump-administration official Deborah Birx. Kranz’s summary work has not been well-received, mostly getting terse, one-star reviews such as “sad excuse for a book.”

Are these books even legal? I emailed my friend, a copyright lawyer. He wrote back that these summaries seem to go well beyond “fair use,” referring to the legal doctrine that allows people to quote short excerpts of copyrighted material without permission.

A few months later, I was still stewing about these rip-offs. But I felt better when I came up with a solution: I’d publish my own Summary of The Puzzler to get insight into how it’s done. Plus, why shouldn’t I get a cut of these summary profits?

The summaries are likely released through a print-on-demand service. These are self-publishing platforms that let you put out your work, either digitally or in paperback. The business model is to print books only when they are ordered, instead of printing several thousand copies up front, which is what traditional trade publishing does.

This allows the service to give the author a bigger percentage of the royalties—as much as 70 percent. It also lets almost anyone with a credit card publish a book, which is why it’s so hard to track the authors down.

The most popular service is Amazon’s own Kindle Direct Publishing. I signed on and spent an afternoon crafting a summary of my own book. I summarized my book’s foreword, including my opening story of being featured as an answer to a clue in the New York Times crossword puzzle, a nerd’s dream. I summarized the second chapter, the one on the history of the crossword puzzle.

And then … I got bored. I empathized with kranz and Humphrey.

So to fill out some pages, I cut and pasted a LinkedIn article I wrote about what puzzles can teach us about life.

After uploading the text, I got to play publisher, which was oddly empowering. I chose the font (Libre Baskerville) and the cover design (I uploaded an image of the famous nine-dots puzzle, figuring it would distinguish mine from the jigsaw covers. Though tempted, I didn’t take advantage of Kindle’s free clip art, broken down by category. For instance, the “Character trait” section offers a photo of a pudgy kid double-fisting hamburgers, which I guess is for gluttony.)

I entered my credit-card information and pressed “Submit.” Two days later, I received an email from Kindle Direct. The news was not good.

While reviewing the following book(s), it appears to be a summary, study guide, or analysis of another book:

Your book(s) does/(do) not comply with our Kindle Content Quality guidelines as it/(they) can confuse customers into thinking they are purchasing the original source material.

What? Then how did the other summaries make it through? Were they published via another service?

I searched for my rival summaries … and they were all gone. Erased from Amazon. It seems that Jeff Bezos does make an effort to crack down on the summary genre. In 2019, an Amazon spokesperson told The Wall Street Journal that book summaries must be “sufficiently differentiated to avoid customer confusion,” and added, “If we find that a title doesn’t meet these requirements, we remove it promptly.” However, the crackdown is not a total success. I searched and found a bunch of other summaries still out there, apparently having slipped through Amazon’s dragnet.

So it appears I’ll never get rich from selling my own Summary of The Puzzler. But it’s unlikely anyone else will, either, so that’s some relief.

SUMMARY OF THIS ARTICLE

Do not buy a “summary” book off of Amazon, because they are nonsensical word salads created by bots or lazy cut-and-pasters with a shaky grasp of the English language.

However, as AI gets better at summarizing books, nonfiction authors might be in trouble.

In the meantime, buy my book!