Autobiography is only to be trusted when it reveals something disgraceful, wrote George Orwell in his essay on Salvador Dali. Perhaps memoirs need merely to reveal the unsuspected.

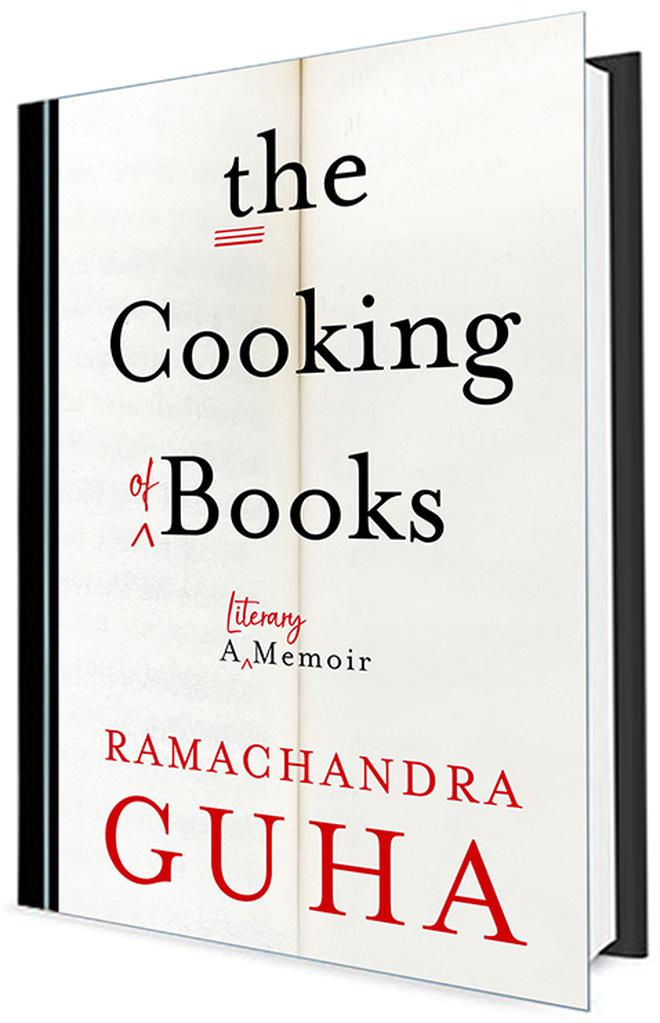

Ramachandra Guha’s paean to a friendship, The Cooking of Books, reveals unfamiliar aspects of this very public and very private person. No warts, but maybe a few scratches. There are too tributes to teachers, mentors and colleagues in the story of a bond both unforeseen (in college one was a ‘scholar’, the other a ‘sportsman’) and inevitable. This duality exists in the relationship and its expounding by the author of India After Gandhi.

The scholar is Rukun Advani, and Ram (familiarity breeds contraction) says, “Had I not met Rukun Advani, I would probably not have become a published author. Had he not befriended and guided me…my move from social history to biography would surely have been far more tortured and infinitely less satisfying. Had I not had Rukun to instruct and encourage me, I may never have thought of writing books on cricket…”

All of us, then, owe Rukun a debt of gratitude for shaping the most varied and stimulating writer of our time. Ram has kept up a correspondence with his first editor that forms the basis of the book.

In St Stephen’s, Ram saw himself as a cricketer; Rukun was a topper in English and a western classical music aficionado. The scholar-sportsman dichotomy didn’t last long, but another remains. While the writer is gregarious and outgoing, the editor is introverted, even reclusive.

Rukun’s temperament and Ram’s self-awareness keep the exchanges between the two, and indeed the book itself, from slipping into the maudlin. Written at a time when both are in their sixties and can look back on a lifetime of achievements, it is (among other things) a peep into the world of Indian publishing too.

Rukun’s notes on Ram’s writings, and his cultured, erudite responses are a special treat and should find a place in our journalism schools. “What makes Rukun Advani a great editor,” writes Ram, “is that he understands language, and he understands thought.” They didn’t always agree, and then the exchanges had a frisson that only two friends can summon up.

For what Rukun wrote about Ram, here’s the start of an essay in the festschrift on the latter’s sixtieth birthday: “Apparently we met on a college badminton court…in about 1974. Since Ram did not go on from the badminton court to become the father of Deepika Padukone, this first encounter’s location was not an augury of the direction of Ram’s future fame.”

I loved two other aspects. The footnotes (this is an academic writing, after all!), full of humour and tantalising digressions, and the gossip, especially about Stephanians like Shashi Tharoor and Amitava Ghosh among others. This is not a historian slumming it, but one bringing the same rigour into a personal story.

The elegiac air, however, is unmistakable. The nostalgia is both for a period in publishing and a friendship that respects reclusiveness. It is a journey from the effervescent to the poignant.