One of the longest-ever follow up studies of breast cancer patients has found that radiotherapy does not appear to improve survival after 30 years.

Researchers found that radiotherapy with either chemotherapy or the hormone drug tamoxifen after surgery does reduce the risk of the disease returning in the subsequent 10 years.

But it makes little difference to that risk thereafter, researchers said.

Nor does it improve overall survival after 30 years, according to the new study, which is being presented to the European Breast Cancer Conference in Spain.

We found that there is no long-term improvement in overall survival for those women having radiotherapy. This may be because, although radiotherapy may help to prevent some breast cancer deaths, it may also cause a few more deaths.— Professor Ian Kunkler

But other academics point out that the women included in the study initially had treatment three decades ago, and since then more sophisticated radiotherapy treatment techniques have been developed.

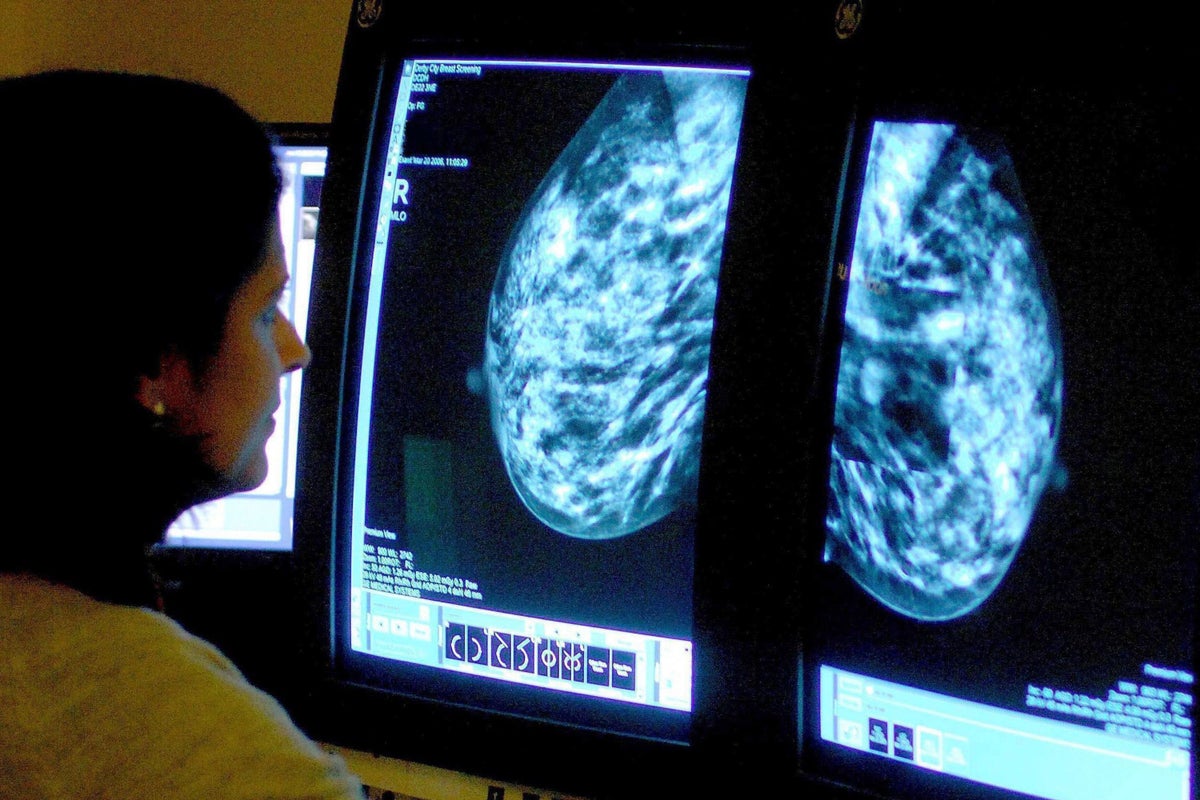

The new research, led by Ian Kunkler, honorary professor of clinical oncology at the University of Edinburgh, is one of the longest follow-up studies tracking patients who received breast conserving surgery.

The Scottish breast conservation trial tracked 585 patients for 30 years.

All of the patients were under the age of 70 at the start of the study and they were all diagnosed with early breast cancer.

After surgery they were given chemotherapy or the drug tamoxifen – depending on whether or not their cancer was driven by the hormone oestrogen.

Half of the patients also had radiotherapy.

A decade after initial treatment, the risk of breast cancer recurring in the same breast was reduced by more than 60% among the group who had received radiotherapy compared to those who did not.

But after the 10-year mark, the risk of recurrence was similar in both groups.

Meanwhile, 30 years after their treatment, 24% of women who had radiotherapy were still alive compared to 27.5% of those who did not.

“Long-term follow-up is essential in breast cancer trials so that we can understand the full picture,” Prof Kunkler said.

“These data challenge the idea that radiotherapy improves long-term survival by preventing recurrences of cancer in the same breast.”

He added: “We found that there is no long-term improvement in overall survival for those women having radiotherapy. This may be because, although radiotherapy may help to prevent some breast cancer deaths, it may also cause a few more deaths, particularly a long time after the radiotherapy, from other causes such as heart and blood vessel diseases.

“The benefits of having radiotherapy in terms of fewer local recurrences are only accrued over the first 10 years after radiotherapy; thereafter, the rate of local recurrence is similar whether or not patients had radiotherapy.

“Patients with breast cancer can live for decades after treatment for the disease.

“These findings warrant comparison with other studies of similar design through long-term, careful follow-up.”

Prof Kunkler added: “It’s important to note that every woman with breast cancer is different and will have different forms of the disease.

“Decisions about whether or not to have radiotherapy after surgery should be taken by patients and their doctors after careful discussion, taking into account the individual characteristics of their breast cancer and the likely risks of recurrence over the long term, both within and outside the breast, and of treatment-related toxicity.”

Commenting on the study, Dr Stephen Tozer-Loft, head of radiotherapy physics at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, said: “The work described is significant and precious because it shows the value of a commitment to very long-term follow-up of patients undergoing cancer treatment.

“However the study’s strength is also its weakness in that it involves patients who were treated more than 30 years ago.

“Since that time, an awareness of the impact of radiation on sensitive organs at risk, in particular the heart, has led to the development of much more sophisticated treatment techniques which significantly reduce the radiation doses received by the heart during radiotherapy compared with a standard breast radiotherapy technique delivered 30 years ago.”

He added: “One would expect that the particular statistical outcomes of patients undergoing treatment now or in the future would be quite different (better) than those pertaining to patients who were treated 30 years ago.”

Dr Tanja Spanic, co-chair of the European Breast Cancer Conference, added: “I was diagnosed with breast cancer when I was only 26.

“One of the questions that I had, as do many women when they are first diagnosed, is what is the best treatment for me not only to treat the cancer but also to help me live a healthy long life?

“As this very long-term follow-up of patients with breast cancer shows, these are complex issues that patients and their doctors need to consider when choosing the best treatments.

“We need more studies like this that follow patients for decades to get the true picture of the long-term effects of treatments.”