The small beach close to which I live is lined with concrete dustbins that serve as a modesty screen for lovers. Behind every dustbin hides a couple fearful of the moral police. This is urban India 2022, and one is still afraid to love freely. I think of the 18th century poet-courtesan Muddupalani’s erotic epic, Radhika Santwanam (The Appeasement of Radhika), and of Bangalore Nagaratnamma, who reintroduced it to the world. What a brave new world Muddupalani’s was!

“A prostitute had composed the book and another prostitute has edited it.” This was what the Telugu literary magazine Sasilekha had to say about Bangalore Nagaratnamma’s edition of Muddupalani’s Radhika Santwanam. A sringara prabhandam or erotic epic written in 584 verses, a sanitised version of this literary gem was first published in 1887 and re-issued in 1907. But it was Nagaratnamma’s edition of the text based on the original palm leaf manuscript and reprinted in its entirety in 1911 that attracted censure, leading to its eventual banning.

As Sandhya Mulchandani points out in the introduction to her English translation of the epic, when copies of the book were sent to the official government translator, he declared that it was obscene and reiterated that both the author and the editor were prostitutes. Almost overnight, a text that was well regarded in the 19th century, was banned. It was only after Independence that the ban was withdrawn by the Chief Minister of the Madras Presidency, Tanguturi Prakasam.

Muddupalani (1730-1790) and Nagaratnamma (1878-1952) were independent and artistically-gifted courtesans who made a mark in the public sphere. In a climate charged with Victorian prudery and the assertion of a middle-class respectability that rested on the careful control of female sexuality, both came to be seen as women of “ill repute”. Their dismissal as prostitutes was a gross mis-reading of context.

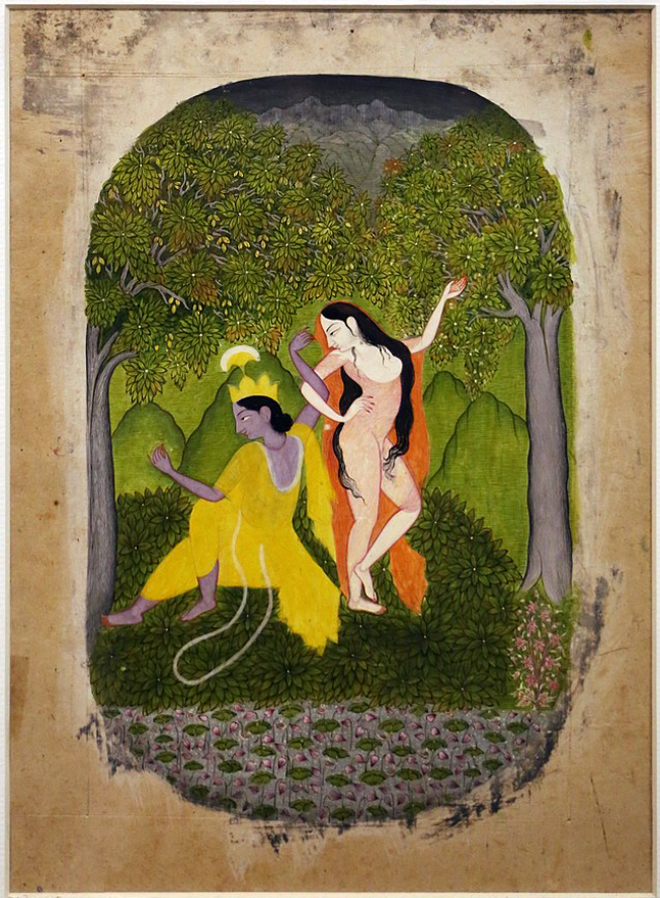

Radhika Santwanam is the story of Krishna’s aunt, Radha, who raises a young girl, Ila Devi, and gives her in marriage to Krishna. Complicating matters is the fact that Radha herself is one of Krishna’s lovers and is not yet emotionally ready to give him up to Ila. It falls to Radha to advise both Krishna and the young Ila about lovemaking. At one point, she accuses Krishna of having abandoned her and the latter then has to appease her. For his part, Krishna complains that Radha insists on pursuing him even when he is not interested. The poem is framed as a dialogue between the sage Maharishi Suka and King Janaka. Muddupalani, clearly aware of the explosive nature of her material, absolves herself of all narratorial blame!

It was in Volume I of Susie Tharu and K. Lalita’s Women Writing in India that I first read about Muddupalani and learnt of Bangalore Nagaratnamma’s impressive and determined efforts to rescue her work from obscurity. In their introduction, Tharu and Lalita argue that Nagaratnamma was very clear about her reasons for reprinting Radhika Santwanam. “However often I read this book,” Nagaratnamma wrote, “I feel like reading it all over again.” She also adds: “Since this poem, brimming with rasa, was not only written by a woman, but by a woman who was born into our community, I felt it necessary to publish it in its proper form.”

Nagaratnamma’s was a feminist act of recovery. When Kandukuri Veeresalingam, a social reformer and a novelist, dismissed Muddupalani’s work as being shameless, obscene and lacking in modesty, Nagaratnamma asked him if propriety and embarrassment applied only in the case of women, not men. After all, many great men had written even more “crudely” about sex.

An accomplished dancer and a polyglot who could write in Tamil, Telugu and Sanskrit, Muddupalani was well versed in sringara rasa. Known for her sharp intellect and wit, she came from a lineage of accomplished women. She was the granddaughter of Tanjanayaki and the daughter of Rama Vadhuti, both talented and learned courtesans. She describes her female literary forebears in the Avatarika or prologue. What I found most striking about Radhika Santwanam, apart from its bold assertion of female sexuality, is the confidence with which Muddupalani presents herself in the Avatarika:

Shining bright like the moon amidst stars

A rarity among poets,

Most experienced in the arts.

Fish-like eyes desired even by Manmatha,

She mocks even the lotus flower,

Padmavathi’s face

Is equalled only by Muddupalani’s.

Which other woman of my kind

Has written the Ramakoti?

To which other women of my kind

Have epics been dedicated?

(from Sandhya Mulchandani’s translation The Appeasement of Radhika)

K. Srilata is a writer and independent scholar who is currently writing verse that re-imagines the Mahabharata.