It has stood near the banks of the Nile River for 3,000 years, its colossal stones baking in heat that reaches 122 degrees Fahrenheit, this ancient temple that sits on a desert plain, uninhabited for much of its history but for the slither of a viper or skitter of a scorpion.

On its walls, Ramses III looms above kneeling foes, one royal arm raised in preparation to smite his enemies. There is a gruesome inventory chiseled into the sandstone of the severed hands and genitalia of the defeated.

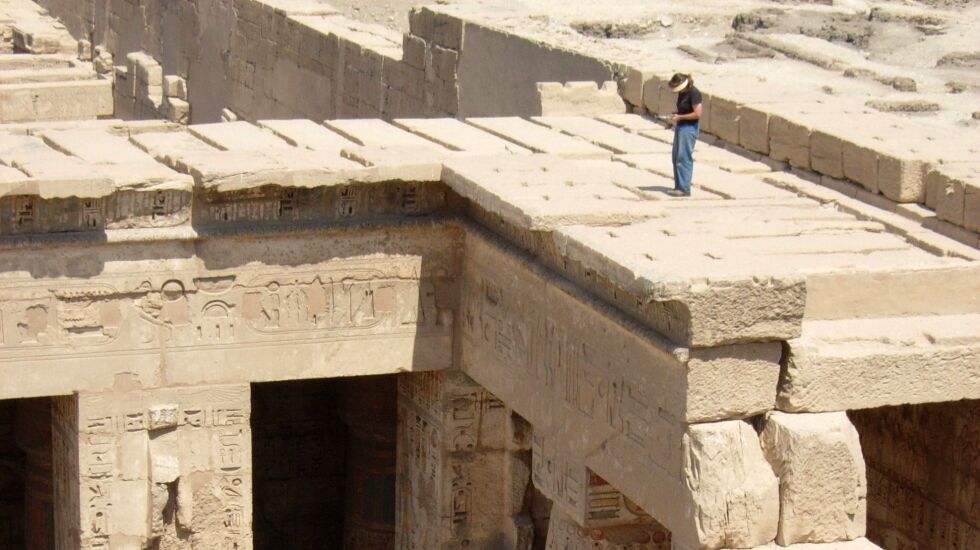

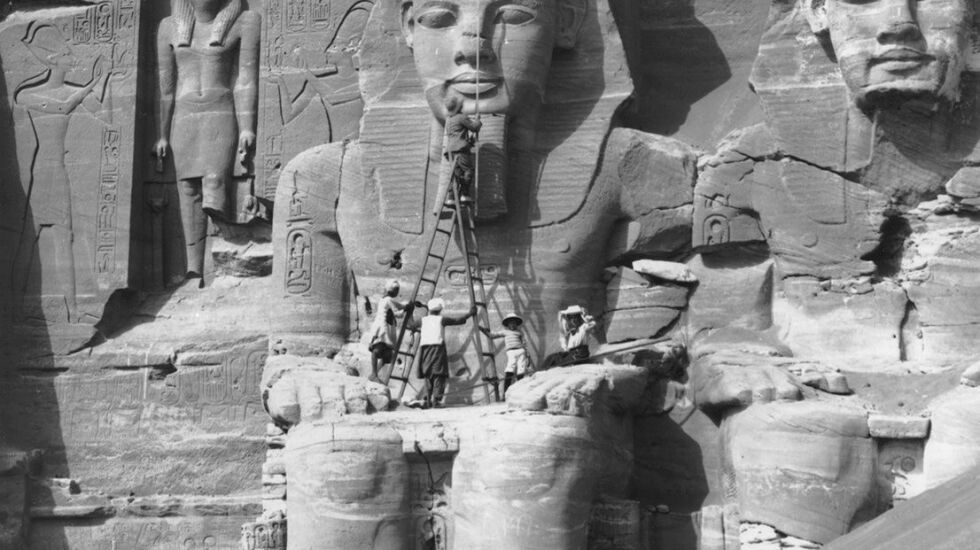

For 100 years, Egyptologists, illustrators and photographers from the University of Chicago have been coming to this remarkably well-preserved Egyptian temple complex called Medinet Habu, bearing cameras, pens and, in the early days, rickety wooden ladders. Their mission has long been to record for history the thousands of ancient inscriptions and carvings in stone.

Now, they are racing to record and preserve the ancient history of this place as climate change and seeping groundwater from neighboring farms threaten to erase it.

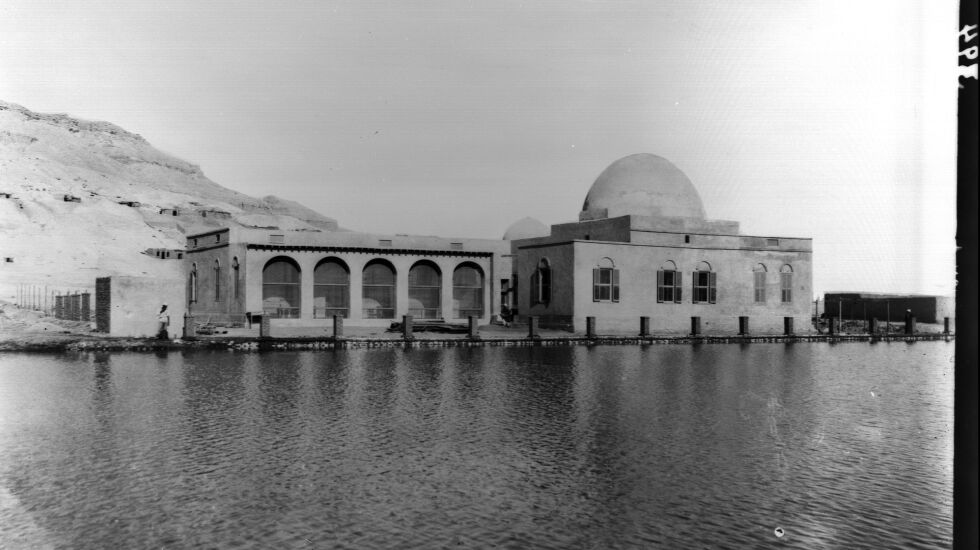

The researchers live together for months at a time in Luxor — at a place dubbed “Chicago House” — much as their predecessors did, working through wars, internal feuds, the occasional cholera outbreak.

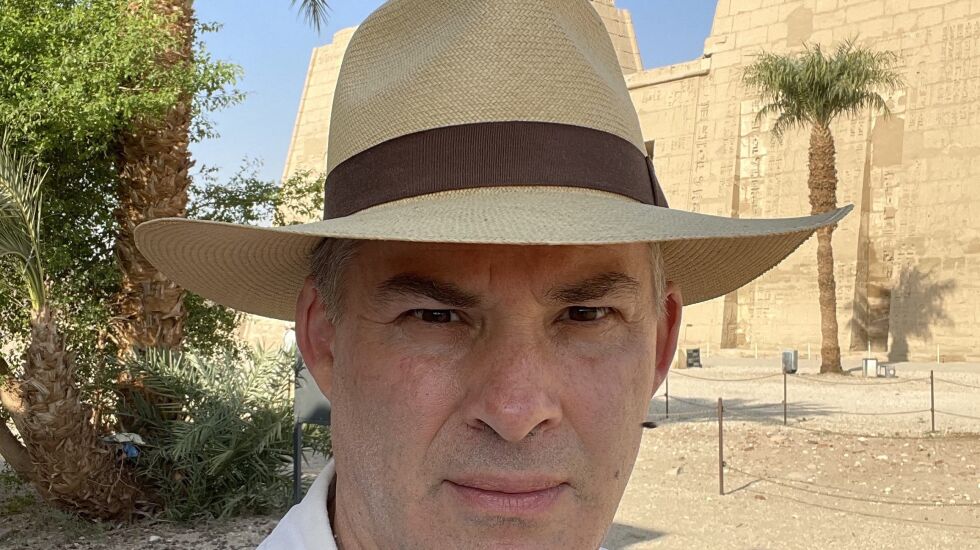

“There are quiet moments when you realize, I’m sitting here in a temple that’s over 3,000 years old, and I’m reading inscriptions that very few other people have ever read or can read,” says Egyptologist Brett McClain, who oversees the operation at Chicago House for the university’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures.

Rockford’s own Indiana Jones

James Henry Breasted was the University of Chicago professor who founded Chicago House in Egypt in 1924. A real-life Indiana Jones, this son of a Rockford hardware merchant began his education as a theology student but distrusted some translations of the Bible and decided he wanted to see for himself the world described in its pages.

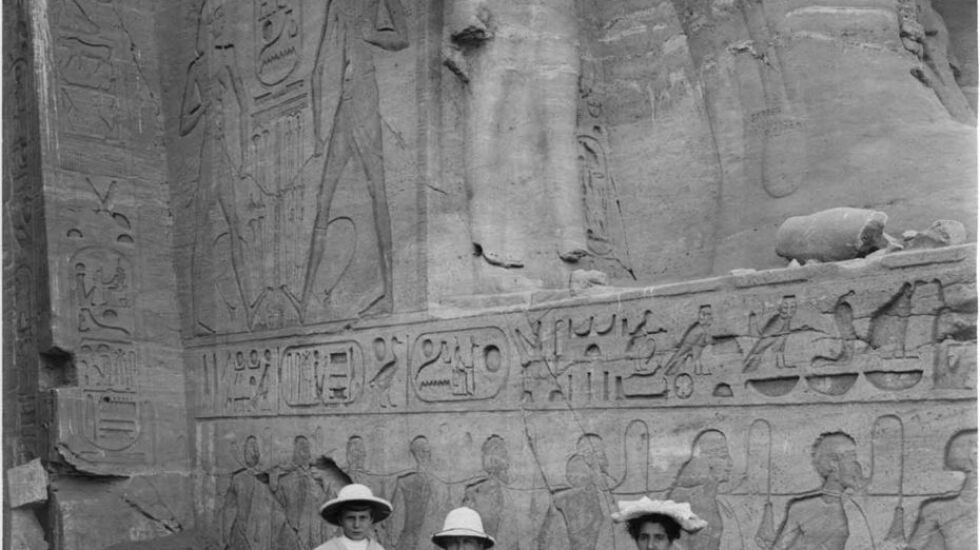

Breasted suffered from “severe attacks of indigestion,” and his doctor told him that, if he must travel overseas, it should be with a doctor or, at least, his wife. So he brought wife Frances and their 8-year-old son Charles to the Middle East along with a civil engineer and a photographer.

“I cannot walk ... to my office . . . but I am going to Egypt if I go on a stretcher!” he said in 1905.

Breasted’s travels ultimately saw him journey by ship, biplane, canoe and donkey. Once, he ended up shipwrecked on the Nile.

In Egypt, he and fellow explorers squeezed into the narrowest of temple passages, taking photographs in “suffocating blackness,” his son Charles Breasted wrote in his 1943 book “Pioneer to the Past.”

Outside another temple, the team was set upon by “clouds of gnats,” scorpions and tarantulas dropping down on them from tree branches.

At a time Americans generally were looking to the future, Breasted preached the importance of preserving the ancient world.

“It is appalling to behold these priceless memorials of man’s past rapidly perishing with every passing year,” he said in a speech in 1928 as president of the American Historical Association. “The monuments of the ancient east are calling for a new crusade.”

A pharaoh’s violent life

Medinet Habu is a walled complex about the size of four Chicago city blocks. To the west lie the ochre-colored Theban Hills and to the east the Nile. The centerpiece of the complex is the mortuary temple of Ramses III, a pharaoh who reigned for 31 years, fighting off multiple invading armies. Perhaps best known for repelling the “sea peoples,” invaders from the Mediterranean Seas, he often led the charge himself, drawing his bow alongside his archers, according to historians.

Armies of scribes celebrated his victories. They’d carve relief scenes and hieroglyphs into sandstone and also depicted feasts, festivals, ritual offerings and gods.

Medinet Habu’s fortified walls house a temple dedicated to Amun, “king of the gods,” and residences for priests, barracks, stables and ponds.

Ramses’ palace was also there. History doesn’t record the number, but it’s certain he had many wives and children. Jealousy infected the harem, Breasted wrote in his 1905 book “A History of Egypt.” Tiy, one of the wives, conspired to kill Ramses in a plot to place her son on the throne. Evidence to support that was found by researchers in a recent CT scan that shows a gash in Ramses’ mummified neck and a missing toe.

“Someone took an axe and put it through his foot, pinning his foot to the floor, then his throat was slit with a knife,” McClain says of Ramses’ killing in 1155 B.C.

Papyrus scrolls detail the trial and the gruesome fate of the 32 conspirators, though there is no record of what happened to Tiy.

“There was some flogging to get them to talk,” says Emily Teeter, a recently retired U. of C. Egyptologist who is writing a book about Chicago House.

The guilty were “allowed to take their own lives,” though some had their noses and ears lopped off as punishment, Breasted wrote.

Scorpions, bickering, bombs

Dressed in a tweed suit and high leather boots, Breasted scoured the Nile valley in search of a place to set up. He chose Medinet Habu because, as far as he could tell, no one else had made a detailed and accurate record of the inscriptions there.

Breasted was not only an adventurer but also was exceptionally good at convincing others to join — or at least pay for — his crusade. Much of the early funding came from a privileged friend — John D. Rockefeller Jr.

The original Chicago House was built of mud brick, with no running water and sandboxes for toilets. The bedposts were immersed in cans of kerosene “because the scorpions might crawl into your sheets and sting you when you got in,” McClain says.

In those early years, a handful of Egyptologists, illustrators and photographers lived in Chicago House with an Egyptian butler and other servants and workers. Then as now, the team spent six months a year living and working together. Feuding was common over something as little as who sat where at the dinner table.

“Three pathological cases … kept me fairly busy and raised the question whether I might not successfully secure employment as a superintendent of a lunatic asylum,” Breasted, back in Chicago, wrote in 1927 to Harold Nelson, the first director of Chicago House.

At one point, police were called to investigate a Chicago House photographer who had roughed up some locals because he didn’t like the way they treated their animals, Teeter writes in her book.

In 1956, during the Suez Crisis, Israeli forces surged across Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. The American government advised U.S. citizens to leave Egypt. The Chicago House team chose to stay even as bombs fell and anti-aircraft shells burst over Luxor.

“The recent events have left us speechless and with the rest of the country, we are shocked by the British-French-Israeli aggression against Egypt and amazed at the stupidity of those who contrived this enterprise,” Nelson wrote in November 1956.

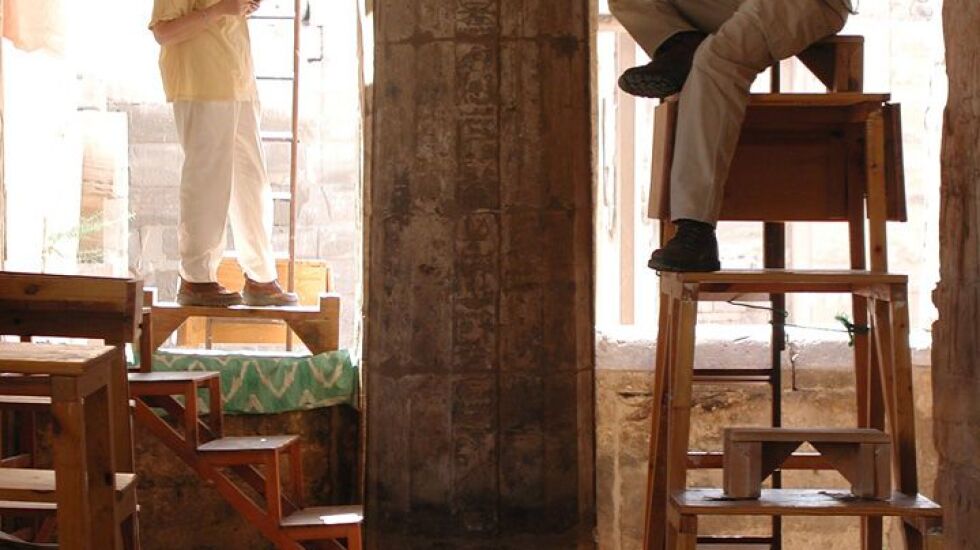

The work at Medinet Habu begins by taking a photograph. Then an artist, looking at the printed photo and the carving, traces the photo in pencil, aiming to capture details the camera might not make clear.

“There is no finer instrument than the human eye for doing this,” Teeter says.

Heads lean in, peer at the sketch and the carving. The Egyptologists suggest changes. Where the stone has crumbled and fallen away, the experts try to determine what likely had been there. The tracing is inked, the photo bleached out. A blueprint is made. Then more corrections.

Only when everyone is agreed will the final pen-and-ink drawing be sent to their publisher.

Those drawings — bound in eight volumes, each measuring about two feet by one and a half feet — can be found in the U. of C.’s Elizabeth Morse Genius Reading Room.

For all of that bulk, today, after 100 years, the work at Medinet Habu is only about two-thirds complete, McClain says.

Mission almost without end

Almost every inch of wall space at Medinet is decorated with some kind of carving — from a horned viper the size of a matchstick to monumental carvings of Ramses about 15 feet tall.

The researchers are working to record for posterity every one of those carvings.

Once, they used bulky, mounted cameras, now replaced by their contemporary digital counterparts and 3D scanning. Otherwise, the work is little-changed. The scientists still carry out their tasks in cramped spaces amid blowing sand, working for hours at a time on a ladder or scaffolding.

The work hasn’t been without risk. One time, an Egyptologist broke both heels in a fall from a ladder. Nelson once stumbled amid the ruins, breaking an arm and tearing a muscle. In the mid-1920s, a photographer died from liver disease after drinking from the Nile.

Racing against time

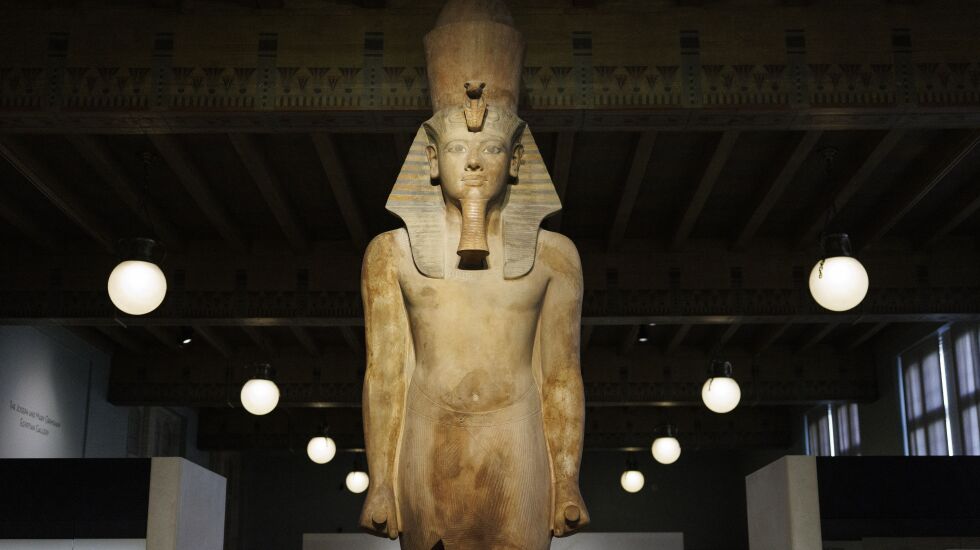

In Hyde Park, the superstar of ancient Egyptian history towers above everything else in the university’s ancient cultures museum — standing 17 feet, 2 inches tall, of red quartzite carved with stone tools. The statue of King Tut is so heavy that steel girders are required beneath it to keep it from crushing the floor.

“When you think about the man-hours [to carve it], it’s absolutely spectacular,” Teeter says.

The statue, dated as having been created around 1325 B.C., was one of two that once flanked a doorway near Medinet Habu. In 1933, the Egyptian government took one. The other ended up on a ship bound for America.

“That was perfectly legal at the time,” McClain says. “In those days, when you got a permit for an excavation, you would split the find.”

Times have changed.

The focus at Medinet Habu now is about preserving history in its original setting.

Though climate change is a long-term concern, there’s a more pressing one right now.

To the west of the temple complex, the hills are treeless and dusty. To the east lies a verdant landscape thanks to agriculture made possible by the completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1970. But what’s been good for the crops can be ruinous for old stone, which sucks up the water like a sponge.

The resulting damage is obvious in a sandstone block from Medinet Habu first photographed in 1994, then again in 2022, after having been left for years in the dirt.

Because of the increased water flow, sandstone that has stood for thousands of years is now disintegrating — becoming desert once more.

“That’s why we do what we do,” McClain says. “The physical monuments may not survive, but, to the extent that we are able to do so, we’ll make sure that their historical information will be preserved for the future.

“We are nowhere close to finished,” McClain says. “The quantity of monumental material in Egypt is so vast that it’s almost inexhaustible.”