It’s an old saying that Britain and America are two countries separated by a common language.

But they are united by racial wealth gaps that formed at a similar time for related reasons. Black Britons of the “Windrush generation,” arriving in Britain from the Caribbean between 1948 and 1973, and Black Americas from the Great Migration of the 1940s-1970s encountered similar disadvantages that were reproduced in the last 50 years.

Today, examining household assets, Black Britons of Caribbean backgrounds have 20 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons. Black Britons of African background – more recently arrived in Britain – have just 10 pence on the £1 compared to white Britons.

In the U.S., Black Americans have assets about 15 to 20 cents on the $1 compared to whites.

This is in large part the result of policymakers in both countries putting up roadblocks to Black advancement at the time they instituted policies to grow the middle class.

In my view as a historian of slavery, capitalism and African American inequality, it’s not just the long shadow of enslavement, which Britain abolished in its western colonies in 1833 and the U.S. ended in 1865 with passage of the 13th Amendment.

When Black members of the British Commonwealth moved to Britain starting in 1948 and African Americans moved from the South to the North and West, they encountered new obstacles.

The long struggle for equal job opportunities has had a lasting effect on the ability to accrue wealth and pass it on to subsequent generations.

The British illusion of opportunity

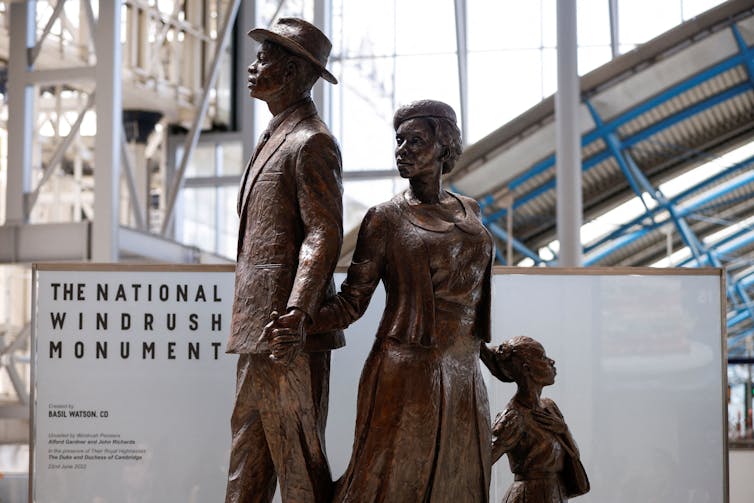

The moment Black opportunity in Britain opened up was June 22, 1948, when the British ship Empire Windrush docked on the River Thames, disembarking 802 passengers of Caribbean background in England.

They led the first sustained Black migration, the Windrush generation, mostly Black and Asian, arriving in Britain between 1948 and 1973.

U.K. employers wanted their labor amid a post-World War II shortage.

About a third of Windrush passengers were veterans of the British forces who served in World War II and recruited by employers for skilled jobs.

Caribbean women, for instance, became vital to the new U.K. National Health Service as nurses, cooks and cleaners, many caring for patients by night and families by day.

But, as British journalist Afua Hirsch argues, they faced persistent discrimination in housing and jobs. Employers wanted them as laborers, not neighbors, and they faced hostility from those determined to “Keep England White.”

When a Bristol bus company refused to employ Black conductors and drivers, Black workers counter-organized, staging a successful Bristol bus boycott against employment discrimination.

Such action led to the 1964 Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, which helped catalyze the 1965 U.K. Race Relations Act banning public discrimination and made promoting hatred based on “colour, race, or ethnic or national origins” a crime.

Meanwhile, civil rights leaders such as Olive Morris fought for economic inclusion through organizations like the Black Workers Movement. These efforts helped include Black workers in unionized industry and led to wage gains.

The American allure of opportunity

While the Windrush generation took shape, African Americans too were moving north and west in search of opportunity. Journalist Isabel Wilkerson contends that “the Great Migration had more in common with the vast movements of refugees from famine, war, and genocide in other parts of the world.”

In the three decades following the Great Depression, the American wage structure became more equal than at any time before or since, a process economic historians term “The Great Compression.” Between 1940 and 1960, the distance between earners in the top 10% and bottom 90% narrowed by a third.

But policies giving white Americans a boost up the ladder tended to hamstring African Americans.

Social Security initially excluded most Black workers. Union wages rose, but African Americans were underrepresented in union jobs.

Home loan guarantees went to white families and specifically excluded Black-occupied properties in many U.S. cities.

Redlining was the practice of denying loan guarantees to properties occupied by Black and other minority residents. It became a self-fulfilling prophesy of disinvestment and declining values.

Meanwhile, post-WWII programs to improve social mobility, like the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, or GI Bill, largely benefited white veterans by expanding the middle class with job, college and home loan assistance.

Historian Matthew F. Delmont argues that “by funneling resources to white veterans and denying loans to Black veterans, the GI Bill intensified the racial wealth gap and shared the terrain of opportunity in America for decades after the war.”

In the 1960s, legal barriers gave way to what African American Studies scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor calls “predatory inclusion” in home ownership, finance and education.

By the time Black Americans began to narrow a persistent wealth gap, the economy was paying diminishing returns to workers.

The wealth-to-earnings ratio rose in the U.S. and U.K. after 1973, and Black Americans who had recently climbed one or two rungs on the ladder started to move backward relative to whites.

Britain’s failed promise

By the 1970s, multicultural Britain had taken shape. As British sociologist Paul Gilroy argues, Black Britain, including people of African and South Asian descent, had become a complex of class and cultures as diverse as England’s imperial geography that once included colonies in Asia, Africa and the Americas.

But diversity didn’t mean inclusion. Just as Black working-class Britons were making gains in unionized industry, that rung of the ladder cracked.

Starting in the late 1970s, factories closed or moved offshore, and ways into the middle class narrowed as the U.K. and U.S. pursued a strategy of more privatization and less government spending on social services.

Union strength declined across sectors, and worker wages stagnated. Many Black Britons were trapped in segregated neighborhoods and didn’t reap gains from rising home values. Today, 2 in 3 white British families own homes compared to 2 in 5 Black British families of Caribbean background and 1 in 5 Black British families of African background.

By the 2000s, those who lacked capital or technological skills in Britain had a hard time climbing up the economic ladder. Income inequality soared between 1979 and the early 2000s, reaching levels not seen since before WWII.

America’s reinvention of inequality

Meanwhile in the United States, legal barriers fell while the economy changed in ways that disadvantaged Black workers in new ways. In 1979 the average Black worker earned 82 cents on the dollar compared to white counterparts. By 2000, the earnings gap widened to 77 cents on the dollar.

The Great Recession of 2008 destroyed half of Black wealth, and in 2015 an estimated 1.5 million Black American men were missing from the economy, having died early, been incarcerated or shut out of the employment market – 8.2% of working-age African American men compared with 1.6% of white men in the same age range.

Despite wealth gains since 2016, Black wealth was more vulnerable and harder to accumulate.

The earnings gap remains wide today.

Black women workers in the U.S. earn 79 cents on the dollar compared to white women, and Black men earn 87% of white men’s wages.

Discrimination across the Atlantic

In the U.K., just before the pandemic, Black Britons of African and Caribbean background earned 85% and 87% of the wages of white Britons, respectively.

According to a study by two leading U.K. inequality think tanks, British women of color endure “intersecting structural barriers and discrimination faced at every point of the career pipeline, from school to university to employment.”

U.K. wealth is largely white, resulting from the “history of economic relations between Britain and the rest of the world, especially Africa, the Caribbean and Asia,” according to the Runnymede Trust, an inequality think tank.

Over the last 80 years, the underbelly of Britain and America is that both countries reinvented racial economic disadvantages.

Instead of making their economies fundamentally fair, racial exclusions gave way to inclusion that came with surcharges on opportunity while failing to rectify past wrongs.

Calvin Schermerhorn does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.