Russia’s war against Ukraine is pressing into its fifth month – despite several rounds of failed peace talks, and Western countries’ issuing severe economic sanctions against Russia.

The war isn’t happening just on Ukrainian soil. President Vladimir Putin’s propaganda is propelling the Ukraine war through Russia media, while continuing to intensify tensions with the West.

This propaganda – whether featuring broadcast as talking points on TV shows, or appearing as the now ubiquitous symbol “Z” – works and will continue to work because it is a tried and true tactic repackaged from Russia’s complicated history.

The appeal of Putin’s propaganda is its repetition. It draws from similar kinds of disinformation used during Russia’s imperial and Soviet eras that recycle age-old narratives of the evil West.

Putin’s popularity is skyrocketing, with 83% of people reporting in the latest estimates in April 2022 that they support their leader. Most Russians also support the Ukraine war.

As scholars of critical cultural and international studies, we think that Putin’s popularity and the widespread impact of his propaganda are not accidental. Putin gives Russians what they have been missing since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 – a surge of national pride.

Appeal to former greatness

Most Russians have long considered themselves patriots, ready to give their lives for a bigger goal: to liberate Europe from Nazism and the toxic influence of the West, and to also unify divided countries that were once united under imperial Russia from 1721 to 1917.

The Russian Imperial Army sacrificed itself for the larger goal of preserving Mother Russia during many wars of this era.

Former Russian Emperor Peter the Great became a national symbol of pride and power in the 17th and early 18th centuries as he waged wars against Sweden and others to expand Russia’s territory. Putin has noted the similarities he shares with Peter the Great.

Political leaders continued to serve as strong figureheads in Russia in later years.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, for example, Russian Communist leader Vladimir Lenin became Russia’s new national symbol of strength. Statues of his face and body appeared at every central square of every city, town and village across the Soviet Union – and many remain intact today.

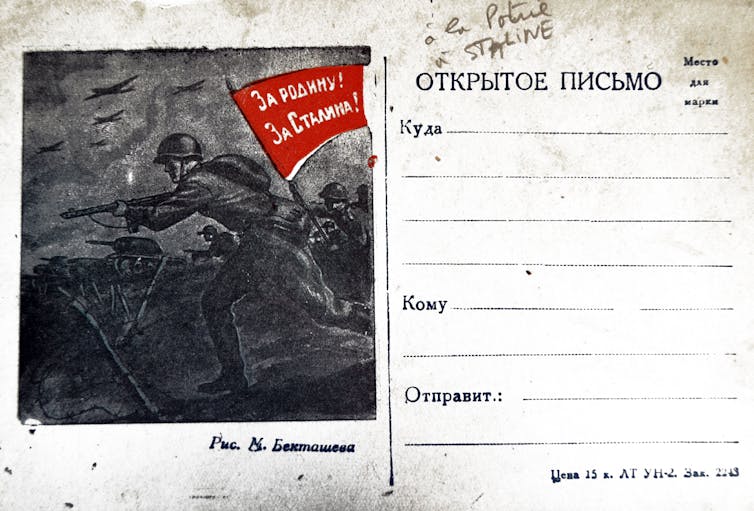

Joseph Stalin rose to power after Lenin’s death in 1924 and became especially prominent as a national symbol and leader during World War II. The war became an identity-crafting experience for the Soviet citizens. Some 27 million people in the Soviet Union died during the war, sacrificing themselves for Stalin and the Soviet Union.

A Renaissance man

Decades later, following the fall of the Soviet Union, another political leader emerged as a new national symbol of unity: Vladimir Putin.

Putin took office in 2000 as a hypermasculine, decisive and fearless leader who took after and aspired to embody previous admired rulers, like Lenin and Stalin. Like his predecessors, Putin was an uncompromising patriot with a historically familiar iron grip on politics.

Yet Putin was also someone who Russians could look to as “one of us.”

Putin plays the role of a strict but caring father to Russian citizens.

As he has cracked down on LGBTQ+ rights and decriminalized domestic violence, Putin has also held annual phone hotline sessions to address citizens’ urgent needs.

Putin also fishes, rides horses and swims with dolphins – all creating an image of him as tough, yet loving and relatable.

Today, Putin’s popularity cult is also tied to the idea of reanimating Russia’s past to reinstate the country’s greatness. This desire to rebuild Russia as an image of its past justifies Putin’s waging a war on Ukraine and the country’s ongoing political and economic confrontations with the West.

Back to the USSR

Putin has reminisced about Russia’s glorious past since the early days of his presidency. In 2003, he issued a modification of the Soviet Union’s state anthem into Russia’s new national anthem, with only minor changes to the lyrics and the same melody.

In 2005, Putin called the dissolution of the Soviet Union a “major geopolitical disaster of the century,” stressing that thousands of Russians were stranded outside of their home country.

Putin’s nostalgia for the Soviet Union has helped him justify different conflicts, like the 2008 invasion of Georgia, for example.

Putin defended the forced annexation of Crimea from Ukraine in 2014 as a reunification with Russia. Similarly, Putin says that the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine has always been Russian.

According to the president’s worldview, the proverbial Russian bear is simply collecting its strayed cubs.

Facing West

Another element of Putin’s appeal to Russians is how he defends the nation against Western powers.

Putin boasts that he is immune to the West’s criticisms and condemns the West, particularly the U.S., for its support of Ukraine and economic sanctions against Russia.

The tightly controlled Russian media regularly parrots the government’s official lines, falsely reporting that anti-Russian sanctions are killing the global economy, for example.

In return, Western criticism of Russia works counterproductively, further unifying Russians and strengthening their patriotism.

Different realities

Narratives in Russia about everything from the Ukraine war to the state of the economy create a very different reality to the one known outside of the country.

The fusion of nostalgia and state-controlled propaganda in Russia ensures people’s support of the ongoing war.

The call to fight against “Nazi Ukraine” has replaced decadesold rallying cries to defeat “Nazi Germany.”

Inspired by the memory of Russia’s fight against Nazism during World War II, Russia is now leading another sacred war – for a world against Nazism, as a banner at a March 2022 event Putin attended read.

The letter “Z” is a new war symbol in Russia that emerged when Russia’s military machinery was spotted rolling down Ukrainian streets in late February.

Since then, Z has grown in its popularity – appearing on military and civilian vehicles, Russian administrative buildings and on walls as graffiti.

Some Russians even wear a “Z” on their clothing.

The Russian government has said that “Z” stands for victory, unification and the new wave of Russian patriotism.

This spirit of patriotism is strong across generations, including among children and teenagers.

Propelled by the powerful propaganda and persuasive historic parallelism, Russia’s propaganda war continues, and it is not going to stop any time soon.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.