Status Quo are one of the most enduring and successful British rock bands in history, releasing 33 studio albums and more than 50 Top 40 singles. In 2007, guitarists and co-vocalists Francis Rossi and the late Rick Parfitt looked back over their rollercoaster career.

Germany, 1978, God knows how many degrees below zero. Rick Parfitt would be turning blue with cold if he wasn’t turning red with anger as we turn up to rescue him. “I am about to die of fucking exposure!” he fumes, having been standing for hours by a broken-down Range Rover in the dead of winter on a quiet back road.

The ungrateful bastard. Us heroes travelling in the other Range Rover used to transport the band – Francis Rossi, drummer (and driver) John Coghlan – and your intrepid reporter across the continent patiently explain to Rick that when we left him there in the freezing cold and went for help, we… er… misplaced his location and got lost ourselves. But hey, we’re here now. Rick (who doesn’t find it nearly as funny as we do, for some reason) jumps in the replacement hire car and we all take off. We eventually make the gig with just minutes to spare…

Amazingly, Status Quo rarely missed a gig in the 70s, despite being on what was effectively an endless tour, despite endless parties, hit album after hit album. But back in 1978 and throughout the 70s Status Quo were a mean, lean machine firing on all cylinders. Indestructible, really.

But before we get into that, let’s backtrack. Back in the 60s, The Status Quo (as they were then called) were a pop band. Their ’67 hit single Pictures Of Matchstick Men was psychedelic bubblegum; the following year’s Ice In The Sun sort of followed the formula. The Status Quo seemed destined to be one of the pack, set for theatre package tours until the interest ran out. There’s only so much of gaudy-coloured shirts with flowing sleeves a man can take. Then Quo sort of went quiet… Very quiet.

They were still going, of course, it’s just that they were playing in faraway British towns like Minehead and Skegness. When they made it back home to London, the band – Francis Rossi, Rick Parfitt, Alan Lancaster, John Coghlan and a keyboard player, Roy Lynes – were shocked to find that music had moved on a bit; a little bit of soul was what bands now needed for credibility. If not that, then a big bit of rock’n’roll was going to be the calling card of the 70s. Gigging with American singer pop Gene Pitney certainly wasn’t going to break the Quo. And when Pitney’s tour manager told them forty-five hundred times to shape up or ship out, it would be the ultimatum that would change their future. Whether they liked it or not, they had reached a crossroads.

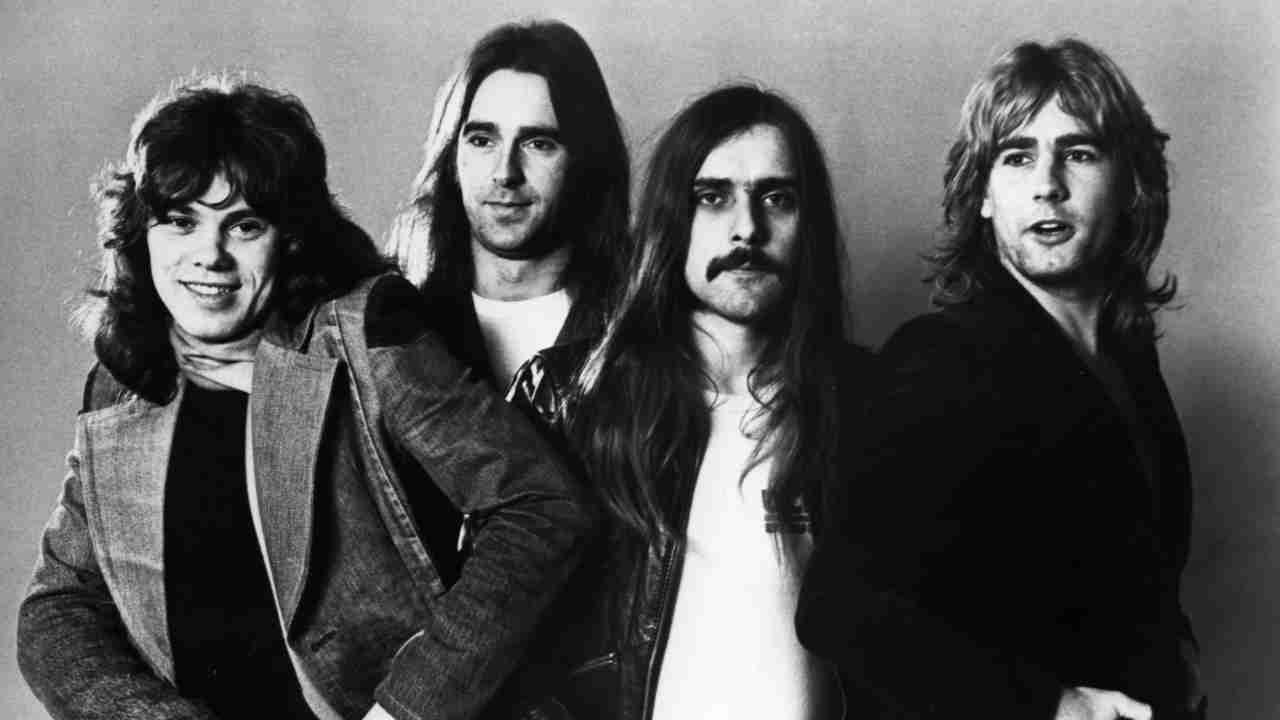

Then in 1970 came two singles in less than a year: the rip-roaring Down The Dustpipe and the equally hard-edged In My Chair, both thundering along like a steam train at full throttle with the boiler popping rivets. Strangely, the group also looked different. As popsters, Quo’s Rossi and Parfitt were sweet-lookin’ boys. But now these guys looked like their hillbilly second cousins, twice removed: straggly hair, torn jeans; like the original Quo set in a parallel universe. As Parfitt would note later: “We just became the dirty, horrible, scruffy Status Quo that everybody knows and loves.”

Also in 1970 they came out with an album that looked cheap and nasty, too, with an old, fag-ashed dame on the cover. Ma Kelly’s Greasy Spoon was the final confirmation that Status Quo (without the ‘The’) had been reborn as a rockin’ boogie blues band; one track, Junior’s Wailin’, was the anthemic epitome of that rebirth. It was a patchy album, but most definitely a sure sign of what was to come from them. And there was a tribe of wannabe Quo fans from all over the British Isles waiting for it to arrive.

“It must have seemed like this sudden change – ‘Quo go heavy!’ – as if it was really planned. It wasn’t quite like that,” said Rossi in 1978. “We were a rock’n’roll band back in ’65 doing mainly covers – Rock Around The Clock , Everly Brothers, Gene Vincent, Johnny And The Hurricanes – and some of our own material. I mean, Pictures Of Matchstick Men was me trying to sound like Hendrix, but it didn’t quite work out.”

Quo certainly weren’t an overnight sensation. They had to earn their breaks – one of which was a gig at the Castle pub in Tooting supporting Mott The Hoople. “The owner put us on, and people were saying: ‘What are they doing here?’” Rossi remembers. “We really went down well, and we liked that challenge, but even the promoter wouldn’t take the risk to put us in his other clubs just yet.”

In time places like the Greyhound in Croydon and the Red Lion in Leytonstone followed, and the local gigs gradually developed into national gigs across the country. The Quo Army was on the move and in recruitment mode. And plenty were signing up.

In 1971 they released Dog Of Two Head. That’s when Status Quo shook off the 60s and embraced the new decade with a new, throttlehead music that would be commercial enough to appeal to anyone who liked their rock raw and the hooks sharp.

They also had the air of a proper band democracy. Even though guitarists Francis Rossi (as main vocalist) and Rick Parfitt would be the more prominent, image-wise, there was no mistaking the quarter share each played by Alan Lancaster, the hard-looking man with the hard-rocking bass, and John Coghlan, the wild man on the kit with a bass drum the size of Africa. (In this new rock world, naturally, they jettisoned the keyboard player.)

Quo were a gang. With them was a team that kept them on the road right throughout the decade, in spite of themselves. How many image-conscious chart groups would have had a roadie-cum-tour manager who also co-wrote the songs and played harmonica on stage, in the studio and on the telly? Enter stage left – as he did most nights – Mr Bob Young. The gang mentality extended to the management, especially when Colin Johnson, who’d honed his skills at the famed NEMS agency (founded by Beatles manager Brian Epstein), was brought in to help take the band to the next level. Alongside an intensely loyal road crew and seasoned PR Keith Altham, this was the squad that would see Status Quo ride roughshod over the 70s, flying in the face of any fancy fad they might encounter along the way.

Quo on Pye Records wasn’t quite working: an old-fashioned label with old-fashioned ideas. One of Johnson’s first deeds in the managerial chair was to secure a deal with the much-vaunted and credible Vertigo label, home to many high-brow rock acts – some of whom were visibly cringing at the thought of Status Quo and their common graces joining their exclusive club. Vertigo’s label manager, Brian Shepherd, didn’t bat an eyelid. “I began to realise that here was an act who’d made it one time around and now I was actually watching them doing it all over again,” he explained. “They were fighting to reprove themselves and they had a manager who’d put his bollocks on the line for them.”

Any decent Quo fan will tell you that Piledriver was the one. From its heads-down, tripartite guitar attack cover, this album delivered everything it said on the packet, from the title and the visuals. Don’t Waste My Time, Big Fat Mama, Paper Plane and a triumphant version of the Doors’ Roadhouse Blues were the pick of the bunch and would be part of the Quo fan’s staple diet for years to come.

Thirty-odd years later, Rick Parfitt still has fond memories of the band’s new birth. “There was no master plan,” he says. “We lived from day to day. Another song, another happy day. All the days were happy. We hadn’t got into any foreign substances. We were just loving it.

“All of a sudden this sound appeared and people started talking about ‘the Quo sound’, and we were saying: ‘What fucking Quo sound? We’ve only got two Telecasters’ – like we still have. Even now, if I play my Tele it just sounds like a Telecaster. If Francis plays his Tele it sounds like another Telecaster. But if you put the two of them together it sounds like Status Quo. We didn’t make it up, we didn’t look for it. It just appeared. And I think we’re very, very lucky. We cornered the market in these kind of rhythms.”

Much would be made from the start of the quirky banter between Rossi and Parfitt, the supposed couldn’t-give-a-damn attitude that couldn’t be further from the truth. As Rossi puts it: “People think we’re humorous and all that, but don’t for a second think that we don’t take what we do seriously. We have a sense of humour, but it doesn’t mean we go out there to be funny.”

It was around this time that this writer entered the orbit of Planet Quo, an Irish writer in the South London home of semi-detached suburban Mr Rossi. Quo had recently returned from an American tour, and that subject framed a lot of our conversation. Even then, the relative inability to break the States was becoming the pain-in-the-ass issue that would dog Quo for years to come. There was the rest of the world falling over backwards in embracing Quo’s no-nonsense boogie, but the good ol’ USA was taking a rain check.

Rossi, though, assured me that the band’s fortunes were on the upturn there. In fact, if they were to set aside five months to work solidly coast-to-coast in the US, the job would be done. But they weren’t prepared to spend that much time away from home at that stage when so much was happening. Actually, he added with some aplomb, they had just blown-out a further three-week stint simply because they didn’t feel like doing it.

“If we break the States, it’ll be when we’re ready,” Rossi tells me confidently. “But don’t worry, they’ll come along with time. The thing with us is that we’re not going to send home all this bullshit about how well we’re doing in the States just to get a few headlines. It’s ridiculous sending home news about headlining 3,000-seaters out there, because those gigs mean nothing. The news is in filling the 20,000 places, and we do that by playing support to bands like ZZ Top.

“But we don’t want to spend more than two months there at a time. We’re successful here and we don’t have to give anything away that’s dear to us. All the States is about at the moment is money, and we’re not too concerned about money. I mean, if it doesn’t happen there it won’t finish us. There are people around who would like to see it finish us but there is no way that it will.”

I was having the same sort of conversation a couple of years down the line (in March 1977) with Rick Parfitt. He was musing on his ambition to be the Number One band in the world, and there was only one thing stopping them from achieving that – you guessed it, breaking through in America. “I still think we’ll do it,” he announced, “but I don’t know how long it’s gonna take. We were paranoid about it at one stage – ‘We gotta break the States or it’s all over’. We’re not worried about it any more. If we do break it, great. If we don’t, that’s the way it is.

“But we’re awkward fuckers,” Parfitt continues. “Colin [Johnston, then manager] says to us: ‘Look, you’ve got to go to the States and do two months, come back for a month and then do another two months.’ And we refuse. We don’t want to go away for that long any more.

“Look, perhaps it wouldn’t be so bad in Australia, where you’re known and you get a bit of treatment, stay in nice hotels and earn a couple of bob. But in America you’re stayin’ in shit holes and nobody wants to know you. You arrive at an airport with all your bags and everything. You’re packed into two hired cars and driven 30 miles to a gig to get pushed in the back door, where you get shown upstairs and find yourself in a broom-closet to get dressed. Before you’re dressed, some geezer says: ‘Come on, you lot, get on!’ It’s literally like that, and they tell you that if you’re not off in 25 minutes they’ll pull the power on you. Fuck all that, mate. Maybe it’s a selfish attitude, but we can’t be like that now because we’re not used to that treatment, and two months of it drives you potty. We’re not going to fuck ourselves up to break America!”

So there you have it, in a nutshell. The one glaring blot on the landscape of Quo’s magnificent decade was down to the fact that the band couldn’t be arsed.

And why would they worry, when a new album that would define their sound was released in 1973? Hello became the definitive Quo album, merging for the first time their raucous hard rock – those glorious 12-bar shuffles – with finely-honed pop sensibilities. Caroline showed the Rossi-Young composing axis at its strongest, and gave the band their first Top 5 single; Roll Over Lay Down, one of the few songs written by all of the band, took further care of the Top Of The Pops audience. For Quo’s ever-growing, maniacally devoted hard-rock fanbase, Rossi and Young had combined to come up with the finest Quo anthem in their history: Forty-Five Hundred Times, a rock symphony way ahead of Bohemian Rhapsody with its four musical movements, and a bit of jamming to really appease the ‘heads’. This was the track that Quo could have used to answer those music critics who rattled on about the “three-chord wonders”.

Of course, Quo were never the darlings of the media. I can remember editorial meetings on Melody Maker where suggestions of a Quo feature brought sniggers of arrogance from most corners of the room. But what couldn’t be denied was that they shifted records and tickets by the ton.

“We’ve had criticism for such a long time now,” Parfitt considered way back when. “These people try to dismiss what we do but they can’t.”

“The music appears simple but it’s bloody hard work,” said Alan Lancaster. “Sometimes we’d go in to do an album and start thinking about what we could do to be different, but then you realise that there is so much more to do within the way we do things. There are so many variations. It’s limitless, really. It’s about how much effort you put into it; how much you want to get into a certain thing and bring the hidden qualities of it out. We play from the heart and not from the head.”

Through the 70s, Quo were very much a unit. There was no frontman out there hogging the limelight; you couldn’t have one without the other. “It gels as a unit,” Lancaster told me once. “We all see things in the same colour. We tend to get the same pictures when we listen to tracks.”

“If Quo packed up I could never go with another band,” Parfitt added. “I couldn’t start over again, getting to know people, getting to know how they play, fitting into another band. I just don’t see myself in another band. We live Quo. It’s always on our minds. You never go through a day when you won’t think of the band. I’m married to Quo more than I am to my wife [his first, as it happened, then]. I see much more of the band than I do of me missus. Primarily in my life at the moment, the band comes first.”

But there was a sneaking feeling even then that the incessant touring was taking its toll. “I like being at home and just generally ticking over, getting a buzz out of the weekend,” Rossi mused. “There’s a certain atmosphere about that. On the road, every day’s a Monday.”

More than anyone else, though, John Coghlan was betraying a tendency to preferring a life at home. “Travelling, basically, is our problem,” he said once over an after-show beer. “Sometimes you don’t realise how hard you’re working, and suddenly all the sleep is catching up. Other times you find yourself sleeping more than anything else.”

Some time later, I find myself sitting with Rossi in a central-London studio just as the band have started sessions on the album that will be called simply Quo. Even at this early stage Rossi is making no apologies for the fact that this forthcoming album will, most likely, feature music similar to the other massively successful albums recorded by the band during this decade. “If we put out something different, kids have to start all over again and try to get into it,” he says by way of explanation. “They don’t expect us to change the music. They want the ingredients to stay the same, and I don’t see why we should struggle and do our damnedest to change it.

“But… we always make an effort to improve with each album and be a little different within the framework of the band. The fact is that if we changed the music completely, critics would pick up on something else and have a go at that!”

Thirty-three years later we’re sitting in a dressing room on another Quo tour, having the same sort of conversation. In the meantime Rossi has been letting this argument stew, and now it has matured.

“People wonder why we’ve stayed together so long,” he says. “What else am I going to fucking do? I kept my head down after Matchstick Men because I didn’t want to be a one-hit wonder, and when I put my head up again we have something like 50 hit singles. We’ve made some horrendous mistakes, but we’ve never analysed what we do because we’d fuck with it. How do we do it? I don’t know. Try and work out what we do and you fuck with it. Lots of things happen by chance.

“Something else happens when we play together. It’s not like we say: ‘We’ll do what we do, shall we?’ We just do it. I do think if you start fucking with it it’s over. Like Bowie and a few other acts – ‘I need to stretch my audience… I’m not doing any of those hit songs any more. I’m not that artist.’ Who the fuck are you, then?! What’s that about? Iron Maiden have said that too: ‘We like to stretch our audience…’ You pompous fuck. You’re desperate for them to love you when you’re growing up. They love you and they buy your albums, and then you say: ‘Just a moment…’ Hang on a second, mush.”

He pauses for a second and muses: “That’s the one thing about me – I think I am competitive. Inasmuch as I’ve been in this band and prostituted myself all over the world only to keep the name alive, to sell more records and more tickets.”

Would he do anything for the band?

“I have done, let’s face it. I’ve got eight children that I barely know [a joke, by the way. We think]. I’ve been away all my life, but… I love going home. But I wanted this so bad that I manifested this when I was little, to the point of selfishness. My, er, current wife understands that. If I don’t do it, we don’t eat. We have to maintain the status quo.”

Meanwhile, back in the 70s the Quo machine is rolling around the world like a juggernaut. So could they give a monkey’s what anybody but their fans thinks of them?

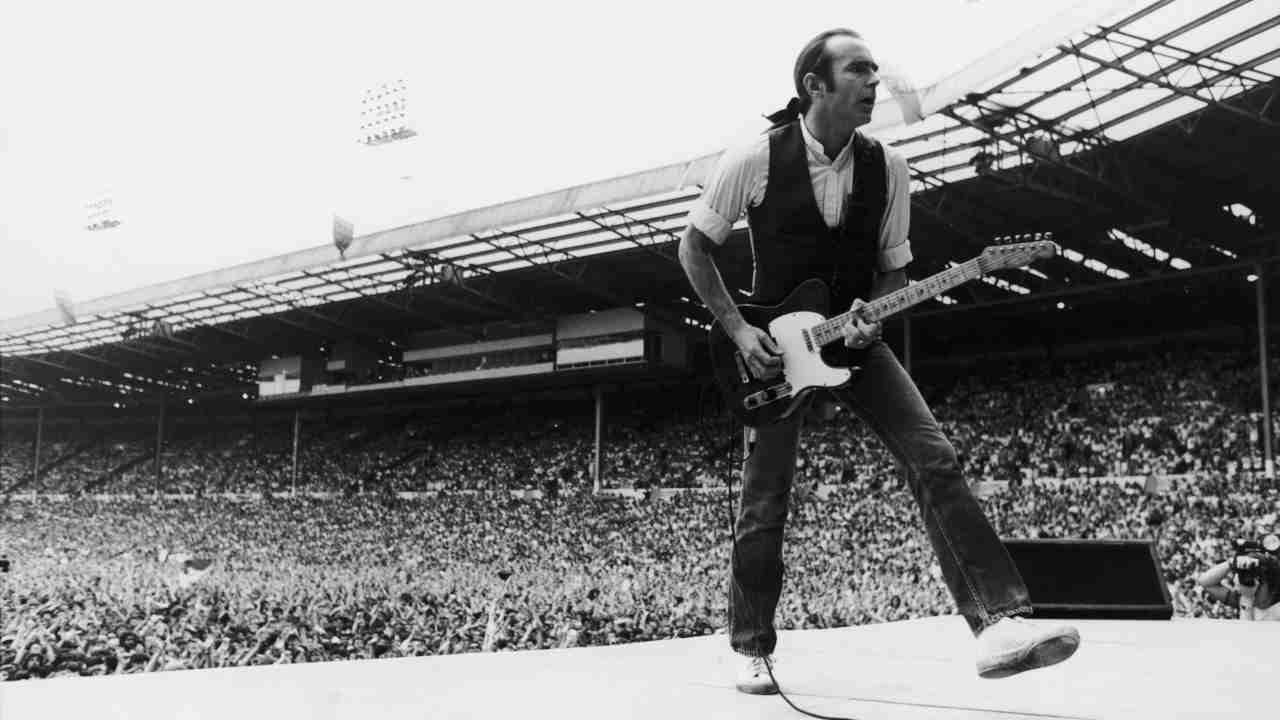

“I think most people know what we’re best at. We’re best at rocking,” Rossi says. “That’s what the stage act is all about – feel for the music. Anybody can go up and do what we do, but whether they do it with feel is another matter completely. That’s what Quo is all about, and that’s what our audiences get turned on about. You see, the thing about a 12-bar, the ‘chunk, chunk, chunk’, as the press describe it, is that there is nothing more teeth-grinding and sexy when we hit it.”

And hitting it they were – constantly. Hitting it in the studio and banging it on the road, and enjoying themselves in the process. Booze and dope had also started to fuel the tanks. Parfitt would explain it thus with his new-millennium clear head: “We started smoking cannabis and stuff, because everybody was. It was everywhere – festivals, gigs. And that brought out another creative streak in ,us because we started thinking deeply about things. It was so enjoyable, and then it got unbelievably funny.”

Bringing out an album each year – which sounds ludicrous these days – Quo somehow managed to sustain their commercial peaks, surpassing previous achievements with each release. On The Level, in 1975, became the band’s second No.1 album, and gave them their first No.1 single with Down Down, a track so basic and straight-ahead with a hook aimed at the man in the street that it gave their critics yet more ammunition. In 1975 Quo were celebrating a decade in existence – which was five years more than the length of time they anticipated when they first started out in this torrid business.

“In those days, no matter who it was, no one was going to last more than three to five years,” said Rossi. “I remember Lennon saying that. We signed our first record deal in 1966 and we had our first hit in ’68. In my mind that time span of two years is massive, but we were that much younger.”

Had they had ever considered calling it a day?

“We haven’t,” said Parfitt. “Really. But the band has got to end some time. But how does a band end? I don’t know. Is it when somebody says: ‘Right, no more gigs, no more records’? I can’t imagine how the band will finish because it’s such a way of life now. It’s a whole chunk of my life. I don’t know how a band ends. You tell me. I suppose it’ll become apparent some time but it won’t happen for a while yet, not while we can rock.”

It happens to the best of bands: they become big – very big – and a maelstrom is swirling ferociously around them; there’s no time to think about the next move. Then, just when there is, along come the demands to record the next album, rehearse for the next tour, jump onto the promotional treadmill… Which is just happened to Status Quo. And the band took the same escapist route that most successful rock bands took when they found themselves in that position: they hit the booze and the drugs.

But back then, after their On The Level album and even through the frequent drug-induced haze, Rick Parfitt could see that Quo needed to get back to top form. “We’ve diverted a bit away from the formula with each album,” he said back in 1976. “Now I think it’s time to get back to that hard-driving rock thing which Quo initially broke the country on. Francis Rossi and [band manager and harmonica player] Bob Young’s writing has been suffering a bit of pressure, whereby they feel that they should write something a little different from the Down, Downs and Carolines, but I think they’ve got themselves sorted out again.”

Actually, next album Blue For You was memorable not for Rossi/Young compositions, but rather for two songs written by Parfitt that showed his immense progression and maturity as a writer and vocalist: Rain, a slice of chugging rock that’s a little bit left of centre, became a firm favourite with Quo fans; the same goes for Mystery Song. Both showed that Quo could indeed mess with the ‘formula’ while not straying too far from the core.

Blue For You was yet another UK No.1 album. And this time Quo found themselves with corporate sponsorship. As the album sleeve shows, this was a work tailor-made for a company like Levi’s. (The band say they never got a whiff of the sponsorship dosh that changed hands, however.)

In Parfitt’s mind, when we spoke in March ’77, the previous year had been a solid one for the band. “That aspect of climbing and getting bigger has gone,” he reckoned. “Status Quo has made its mark, and we’ve got to maintain a standard now rather than build to one.” He thought they’d gone through a “shaky transitionary period”.

“Perhaps we wanted to experiment a bit and do things a little bit differently with Blue For You. We’ve done it and it’s okay, but we want to get back to full-on rock now.”

Parfitt referred to Blue For You as a hapless victim of the transition. He wasn’t keen on the production (“too jumbled”) and felt that the playing and singing wasn’t up to standard. He almost felt guilty, he added, that it was such a phenomenal success. “I should think that the next album is going to be a real all-hell-let-loose affair. We want to go the other way and get back to rockin’ in a big way. You won’t see too many slow things on there.”

Quo, of course, set off on another endless tour to promote Blue For You, selling out gigs everywhere; No.1s everywhere (except America, of course). During the tour they released a new single that would perhaps be the signal of something that would set the seeds of dissent within the band in years to come.

It was Francis Rossi – naturally – who came up with the idea of covering the country rock classic Wild Side Of Life. Rossi had always had more esoteric tastes than the other members of the band, leaning towards pop and country almost with the same enthusiasm as he did towards hard rock. “Country music is something like ours: it’s basic, simple music from simple people,” he told me way back in 1976. As far as he was concerned, those influences were what made Quo unique. Rossi was still rattling on about it when I saw him last month.

“People have been trying to make albums with us and trying to do three-minute, three-, five-chord tracks. It was almost like trying to make an AC/DC record. And I’m thinking, give us a break. Our early albums, whether it was Ma Kelly… , Dog Of Two Head, Piledriver, things like that, they had strange and incongruous things going on: ‘What the fuck is that doing there?’ Which to me makes Status Quo.”

Those different influences that Rossi refers to weren’t an issue at that point back in 1976 when Wild Side Of Life was a hit single, but they certainly would be later.

A year on, another country-tinged song, another cover. John Fogerty’s Rockin’ All Over the World, gave Quo what would eventually become their eternal anthem. For all intents and purposes Quo took ownership of the song.

The band proceeded to practise what the album title preached, and set off on an arduous tour that took in the Far East, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. Their shows at the (in)famous Glasgow Apollo were recorded, and released as Quo Live, released in ’77 – the year when the mighty Quo defied the punk tsunami that was sweeping through Britain. The way Quo saw it, a live album recorded at what was commonly seen as one of the toughest gigs in Europe (“You had to be good to get out of there alive!” said Parfitt) was the best way to answer anyone who was under the misapprehension that this band could not cut it. Indeed Quo Live is a fitting testament to the band’s performances on the road during that era.

Quo knew had nothing to fear from passing fads like punk. They were a band of the people. “Punk didn’t ride over the top of Quo as it did with other bands, because we rock harder than any of ’em anyway,” said Parfitt. “This band seems invincible somehow, even to me now. There’s some sort of magic to it, which I’m just beginning to realise.”

So the band felt no adverse reaction to punk? Not even a little bit?

“Well, I must admit it frightened me a little bit,” he conceded. “It might have got Quo into the Boring Old Farts bracket, but that hasn’t applied at all. On the British tour there have been quite a lot of punk rockers there and really getting off on it, because they are out, I realise now, for a good rock’n’roll time. They find they can do that with Quo.

“Nothing can sink this ship,” Parfitt continued. “Maybe that sounds like famous last words, but that’s the way it appears at the moment. You’ve seen the gigs. The band are working like bastards now. It’s really, really good. We’ll aim for 20 years.”

But in the classic decade that was the 70s, were Quo producing classic albums? From the start, you’d have to say that each had four or five great tracks, so ‘classic’ is hardly the word. But, taken as a whole, what Quo achieved on record and on the road did constitute a classic era for them.

And, looking back with the benefit of 30 years’ hindsight, Rossi’s view tallies with that. “I find that ‘classic album’ term all a bit too simplistic,” he says. “Like I said before, what does it all mean? It’s only a classic album for people that like that shit. For people that don’t like it, they couldn’t care less. The word ‘classic’ is bandied around a little too much these days. People say: ‘Oh yeah, the Piledriver album – what a classic.’ I’ve listened to that album: great in parts. Some of Hello is all over the shop, but there are some really great moments in there, coupled with some shite. And that’s true of music generally.”

Where the term ‘classic’ really applies to Status Quo is when it comes to their live performances. During the 70s their touring schedule was relentless, and as we eased through the winter of early 1978 I found myself on the road with them once more. What highlighted this tour was that it seemed to encapsulate everything about Quo at that point: drama, laughs, the increasing drug culture, a certain feeling that the wheels were, if not coming off the tour bus, then loosening a little bit. Let me tell you about it…

We’re in Dortmund. It’s 6.30pm, the doors have just opened at the Westfalenhalle cycling stadium and 10,000 headbangers are piling in to see Status Quo, who at this time the biggest rock band in Germany.

Quo have a certain pride in touring. Back then they had only ever cancelled three gigs in 10 years on the road. For the previous couple of weeks the band had been trekking through Europe in sub-zero temperatures, facing blizzards and reaching destinations literally minutes before making it onto the stage.

Germany loves Quo. More than 200,000 copies of the Rockin’ All Over the World album found their way into a home there, and this tour of 6-10,000-seat venues sold out in hours. As in other territories, Quo’s growth in Germany had been slow and methodical, but the band knew that once they’d made it they would not become ships that passed in the night, as had happened there in the previous couple of years with The Sweet and Smokie.

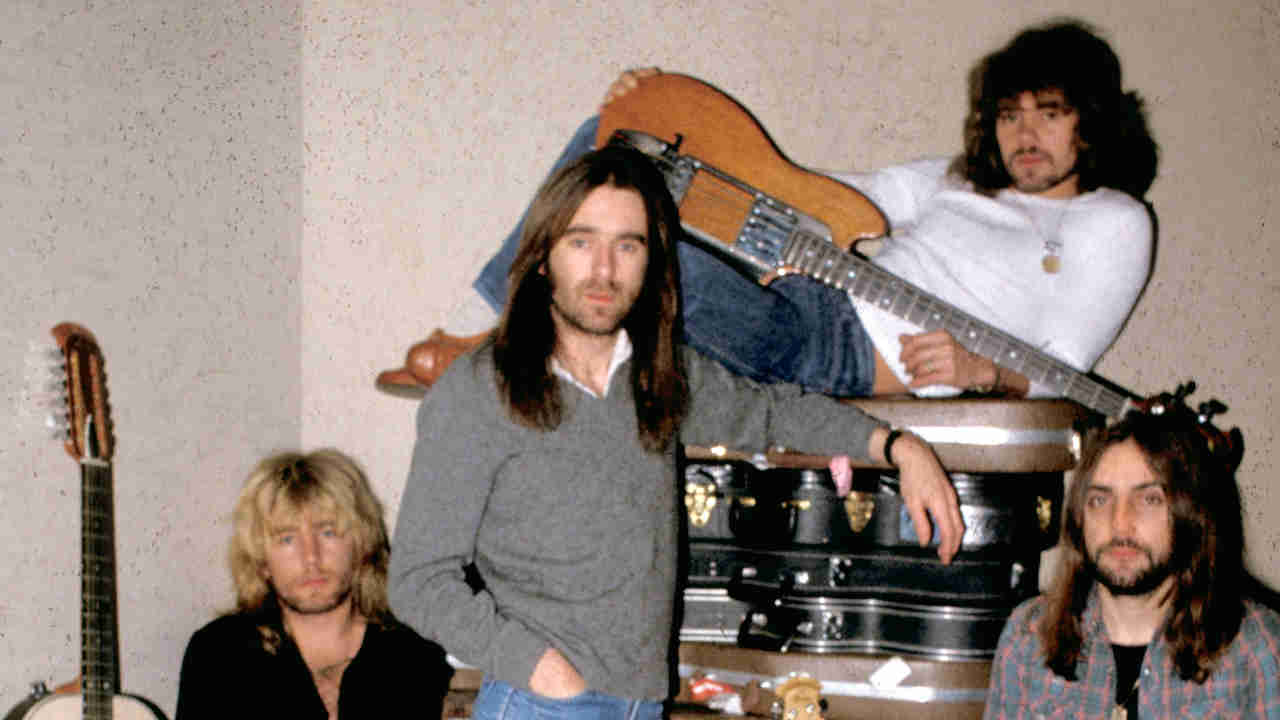

This was Quo’s first tour with keyboard player Andy Bown, brought into the band on Rossi’s instigation to add more colour to the sound. Bown had come with a reputation as a real muso. He was an original member of popsters The Herd and was trying to keep it quiet that he was the composer of the theme tune for Mike Mansfield’s TV pop show Supersonic. Bown had guested on Hello, and in the intervening years was slowly sucked into the Quo set-up, his own solo career eventually playing second fiddle.

Could he have known what he was letting himself in for? Quo on the road was a bit of a circus. Manager Johnson was on this trip in an attempt to keep the band in check – and especially to ensure that Parfitt and Lancaster made it to the gig in Vienna safely. On the previous trip there the two had been thrown in the cells by over-zealous cops. Well, Parfitt and Lancaster had picked a fight with them.

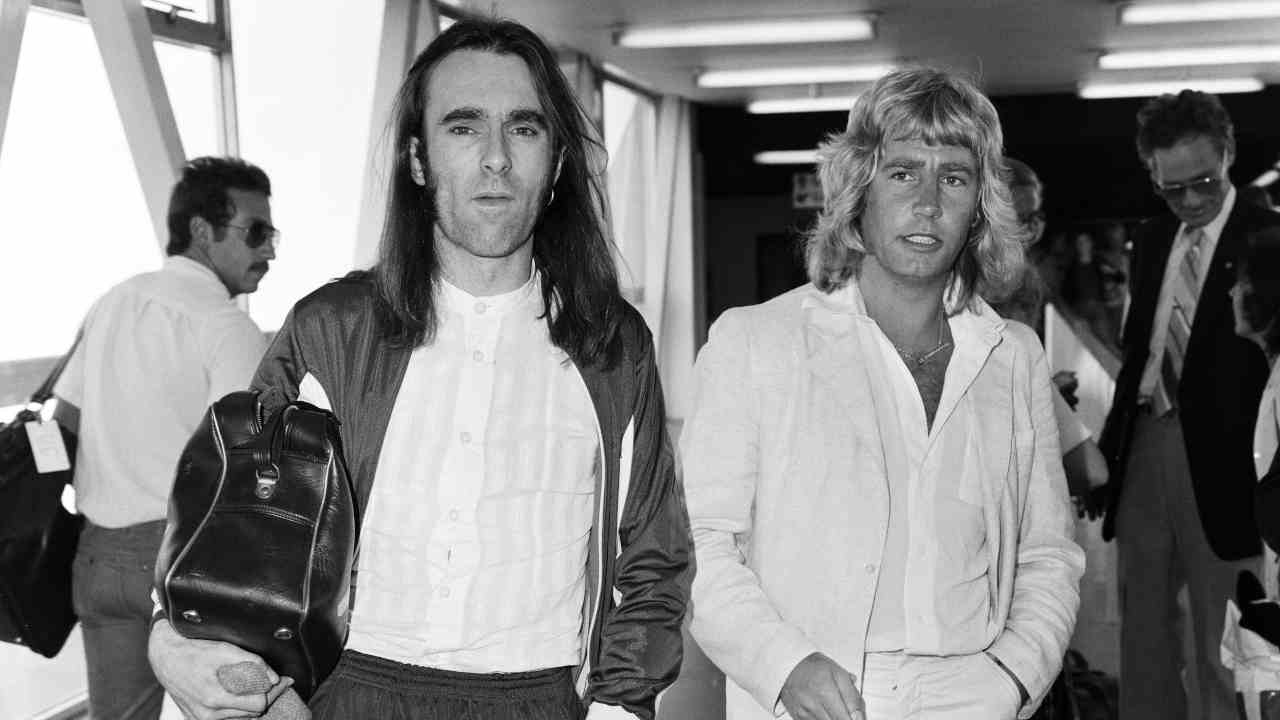

Quo’s touring arrangements have never been straightforward. Not for them flying all over the place. In 2007 they travel around in a couple of luxury coaches. Back in ’78 they liked driving in their vehicle of choice, which happened to be Range Rovers. So each morning, the band would set out in two white RRs, one driven by drummer John Coghlan, the other by Parfitt, travelling in tandem at high speed to the next gig.

On this particular Saturday we’re speeding along the autobahn to Wolfsburg, another great gig.

“I’ve said it before, but there is really no audience like a Quo audience,” Parfitt tells me afterwards. “I’ve seen other bands, and there is just something different, and the way people react to Quo is just something different; there’s a love there, there really is.

“We know there’s power in the music and we know there’s a power in the combination of the four people in the band. We don’t need to pull any stunts. We’ve escalated so slowly. It’s been beautiful. Year by year. And the band is now bigger than it’s ever been. All over Europe. We’ll outpull anybody in Europe now, including the Stones. That’s a feat in itself.

“I’m not trying to make it all sound rosy, there are internal problems. After 16 years there’s got to be. We don’t get on so well as we did, and a couple of us have split socially. We don’t have quite so many laughs as we used to have, but that’s no problem.”

That was the first admission that all was not as it once was in the Quo camp. Little cracks were appearing in the walls of the fortress.

That evening I sampled Quo’s unique hospitality on the road. Being on the road so much, the band and their entourage had tired of the usual dull routine of the post-gig drinks back at the hotel or hitting a local club. So they set up their own private club, which would open in a specially booked bedroom at whatever hotel they stayed in – bar fully stocked, security on the door, the whole deal.

That night we all got well and truly hammered. Through the haze, though, I can remember seeing Parfitt and Rossi occasionally float through the room, cocktail in hand. Both looked completely zonked, and not on just alcohol. This was the time when heavy-duty drugs were taking hold.

“We started drinking before we went on,” Parfitt recently recalled of that period. “The bourbon would come out and the Scotch would come out. I would have maybe half a bottle of Scotch before we went on. That got to us a bit. We started falling over and falling off stage. Which is all part of the rock’n’roll bit: pick yourself up, dust yourself down and carry on.”

The next morning we gather in reception as we prepare for another winter trek. I’m travelling with driver Coghlan, Rossi and his spouse of that moment and tour accountant Alan Crux. Johnson commandeers the other Range Rover with Lancaster, Parfitt, Young and Bown on board.

About 20 miles outside Wolfsburg it all starts to go a bit pear-shaped. Johnson pulls level to us, looking a tad annoyed, and signals for us to slow down and stop. It turns out his petrol pump is playing up.

Leaving the hapless CJJ1 with its miserable passengers behind, we scout ahead to the town of Celle for a petrol can, petrol and a tow rope. Unfortunately, upon heading back to rescue the rest of our group we forget where we’ve left them. Two wrong autobahns and an hour later, we find our bearings – and the other Range Rover and its freezing occupants. Parfitt is turning blue and swearing. Alas nothing can be done for the stricken 4x4, so in the middle of nowhere we start looking for a taxi. We eventually knock on the door of the only cab company in a the vicinity, with its fleet of two beaten-up and ancient Mercedes. We take both, and with a fare that involves a 200-mile journey, Quo make the day for the two aging drivers. Who, we suspect, are just a little tipsy. But needs must.

We get to the gig eventually, as always. As ever, the problems of the day disappear with that night’s show at Essen Grugahalle with Quo playing in front of 8,000 wild Germans. The audience is amazing, the venue is perfect for sound, and the band are in a positive mood despite the trials of the day. It was one of the best Quo gigs I’d seen.

Later that year Quo released If You Can’t Stand The Heat, a solid if unspectacular album that spawned one Top 20 single (Again And Again). The album itself peaked at No.3. There was a distinct feeling around that Quo were losing a bit of pace, and that the cracks Parfitt referred to earlier were having an adverse effect. Whatever You Want gave the same impression the following year. Quo were still capable of selling out tours and making hit records, but it seemed that ambition and impetus were out the door, passing an ever-increasing cocaine intake and band bickering on the way in. As the 70s came to an end, so did Quo’s golden era.

As it happened, it took four years before the inevitable happened. The combination of drugs, drink, touring, bickering about writing royalties, suspicions about business handling… All of that eventually took its toll.

The first to succumb to the pressure was John Coghlan, who had never been the chirpiest bird in the cage anyway, and his moroseness only intensified with all those pints of beer.

A few years later, the heightening tension between Rossi and Lancaster finally went through the roof. Lancaster announced that he was disgusted that Quo could record a song as trite and poppy as Marguerita Time. They were a hard rock band, after all. But that song epitomised everything that Rossi loved about country and pop, and as the single went into the Top 5 he felt justified. Lancaster refused to promote it. Jim Lea of Slade was drafted in to cover for him on Top Of The Pops.

The damage had been done. Rossi and Lancaster could no longer stand the sight of each other, and off Lancaster went into the Australian sunset. Rossi persuaded the band that they should take a year off the road and see how they felt after that. Just to push the point home, the tour in 1984 was called The End Of The Road Tour. It climaxed with a headlining appearance at the Reading Festival in front of 50,000 people.

Lancaster launched legal proceedings aimed at preventing the band playing without him. An arrangement was eventually reached that allowed Rossi and Parfitt to continue as Status Quo.

The final time Rossi, Parfitt and Lancaster played together was quite an historic moment – Quo opening Live Aid in 1985. It was a powerful reminder of how popular the band was, but it wouldn’t save them. Lancaster was out. And it would be some time before Quo regained the dignity and reputation they had spent so much time and energy building.

“A lot of the fans were dismayed and disgusted with what had happened,” recalled Parfitt. “It was like starting again, proving ourselves with In The Army Now. We’d done all this work to get the band to what it was, and then it all falls apart. Could we – did we – have the energy to pick this up again and start again? We didn’t have the character of the original Quo, and it’s taken up to now to build it again into a really good band.”

When I saw Quo play this summer in front of 15,000 crazed Swiss fans in Geneva, I was reminded of how raunchy and wonderful the band can be. Yes, there’s only Rossi and Parfitt left from the lethal quartet that made the band’s reputation back in the 70s, but they looked and sounded in rude health, now having buried the shackles that so blighted them throughout the late 80s and the 90s. The set they play is mostly a celebration of all the best material from those 70s albums, with even Down The Dustpipe and Gerundula thrown in. The pace is relentless.

“It is now the greatest band it has ever been,” said Parfitt “But nothing will ever replace that original Status Quo. It was magical. Those years, that decade, is to be savoured forever. I have all those thoughts and memories. Colourful, successful… just amazing. That’s really what it’s all about.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 114, December 2007