-Marc-Brenner-(1).jpeg?width=600&auto=webp&crop=3%3A2&quality=70)

Telling someone the basic outline of this play - the true story of 19 year old Jacob Dunne who threw a single punch at James Hodgkinson outside a pub in 2011 and killed him - is inevitably going to do it a disservice. It would be more helpful to say: bring tissues. Because it’s what happened next, and it’s how the great documenter of our times James Graham deals with it, that turns a tragic story into a truly devastating piece of theatre.

It’s a play set in Nottingham (it was commissioned by Nottingham Playhouse and comes to London after a very buzzy run there) which has the city at its heart: its estates and clubs, its nicer bits and nastier bits and the gulf of inequality between the two. But its fury and empathy are universal.

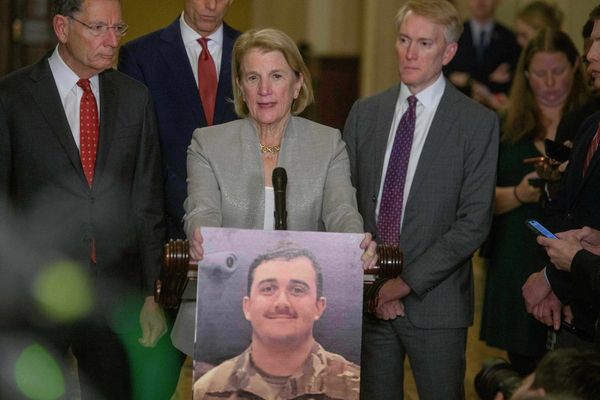

David Shields bursts onto the stage as Jacob, a drug dealer, gang member, amped-up kid desperate for a fight. Shields plays it with such intensity that you can almost see the blood vessels bulging in his eyeballs. And it’s not long before the fatal punch happens. From there the play starts to become more and more complex, as we learn about Jacob’s upbringing on The Meadows estate, the pipeline of drugs and gangs he’s sucked into, as well as the fallout of the punch: a prison sentence, and a remarkable restorative justice scheme that put him in contact with the parents of the young paramedic he killed.

The play isn’t perfect. Sometimes it’s too heavy-handed, too didactic, strangely unsubtle in a way that doesn’t do full justice to Graham’s abilities as a writer. It veers off into lectures about class and urban planning - Anna Fleischle’s concrete and metal railing set looks lifted from a 70s council estate - and palpable anger at austerity, at broken prison systems. It’s kaleidoscopic, and a bit messy.

-Marc-Brenner.jpeg)

But all that is made insignificant by the things that work. First, Shields’s Jacob blazing through the city in the grip of a masculinity that prizes fighting and face-saving; the way he struts, moves across the stage and takes up space. Then the stillness of James’s mum and dad Joan (Julie Hesmondhalgh) and David (Tony Hirst) in their grief. It’s a beautiful bit of directing from Adam Penford, that contrast between the sinewy, fist-first motion of Jacob and then the softness of Hirst and Hesmondhalgh. She is unbelievably good here, so understated and so believable.

Most of all it’s the eventual meeting between them, which will probably be the fourth or fifth time you’ve cried already, but where the tear ducts really start to get wrung out. They take it in turns to ask questions about what happened, about each other, and Jacob gets faced with the immovable object that is Joan’s quiet compassion.

The scene isn’t mawkish or sentimental, nor is it sad really. It’s even quite funny. Theatrically it’s just four people sitting on chairs with a plate of custard creams between them. But there’s something about the rawness of it that reaches into the heart and lungs and yanks those sobs right out. The fact that this happened is astonishing: that two humans were able to connect to another human in a way that defies logic and emotion.

Graham isn't interested in placing blame, nor in excusing what Jacob did. He’s too smart to be that simplistic. Traced back to deep, complex roots by Graham, so carefully handled by Penford, that punch opens up a paradox - a brutal act led to something so positive and hopeful - whose unanswerability is left to hang poignantly, confusedly and hopefully between the man who threw it, and the ones who felt its impact.

Punch is at the Young Vic until 26 April