The new film Conclave is a psychological thriller looking at the selection of the new pope. But what is a conclave, and where did this ritual begin?

The institution of the conclave is the formal process by which a pope is elected.

As cardinals cast their secret ballots, they partake in a process that upholds the Catholic Church’s millennia-old heritage and navigates the dynamics of contemporary global power, making the conclave a powerful intersection of faith, tradition, and geopolitics.

Who gets to be pope?

The pope’s role is deeply rooted in both spiritual and historical significance. The pope is the successor of Saint Peter, one of Jesus Christ’s disciples, entrusted by Jesus with the leadership of the early Christian Church.

The pope serves as the sovereign of the Holy See, the central governing body of the Catholic Church, and the head of state of the Vatican City State. The Holy See holds the status of an independent state in international law and maintains diplomatic relations with other countries and organisations such as the United Nations.

Any Roman Catholic male can be elected pope. But since the Middle Ages, every pope has been selected from the College of Cardinals, the group of highest-ranking Catholic leaders.

Many of the cardinals are archbishops and bishops appointed by the pope to lead Catholic communities in their country of residence.

Who gets to vote?

In the early Church, the Bishop of Rome was elected by the local clergy and laity. Over time, the clergy became the primary body responsible for the election, although the laity initially retained a degree of influence.

In 1059, Pope Nicholas II decreed only cardinals would primarily elect the pope, laying the groundwork for the formal role of the College of Cardinals. This shift marked the beginning of a more structured electoral procedure.

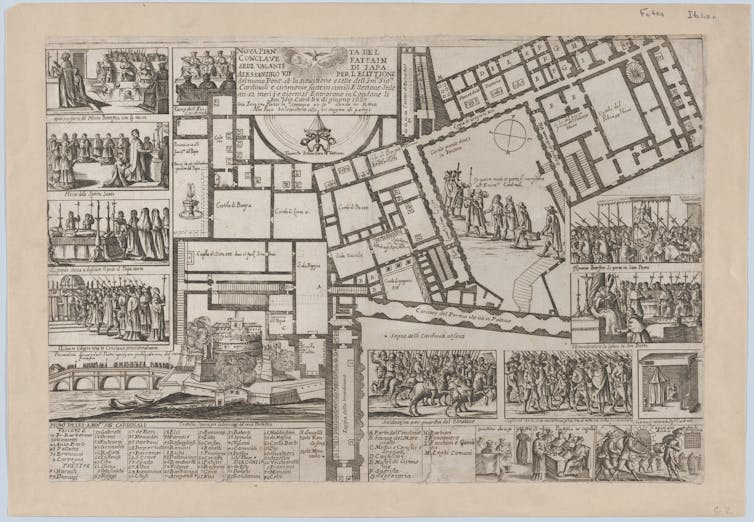

To expedite elections, in 1274 Pope Gregory X introduced the conclave system, sequestering the cardinals and rationing their food until a decision was reached.

The process became further standardised in the modern era. Pope Gregory XV in the early 17th century introduced a secret ballot system and reinforced the two-thirds majority rule, aiming to ensure electoral integrity and prevent manipulation.

In the 20th century, Pope Paul VI implemented significant changes. Cardinals over 80 years old were barred from voting, and the number of cardinal electors was capped at 120.

Today, there are 236 cardinals, and 123 are eligible to vote to elect a new pope.

How is a vote cast?

Various methods have been used to elect the Pope throughout history.

Acclamation, where cardinals unanimously declared a pope without a formal vote, was abolished in 1621. Another method was compromise, where a deadlocked College of Cardinals delegated the decision to a committee; this was last used in 1316.

The current method, known as scrutiny, involves a secret ballot.

Today, the papal election is governed essentially by rules set by Pope John Paul II in 1996. Cardinals reside in the Domus Sanctae Marthae within the Vatican during the conclave, but vote in the Sistine Chapel.

The dean of the College of Cardinals oversees the process, unless he is over 80 and age restricts his participation. Only cardinals participate in the election and, while campaigning for the papacy is discouraged, potential candidates are informally referred to as papabili (eligible).

When a pope dies, the cardinal camerlengo – the chief Vatican administrator – verifies the death and takes possession of the Ring of the Fisherman (the pope’s ring) which, along with the papal seal, is later destroyed to symbolise the end of the papacy.

During the period of papacy’s vacancy (sede vacante) the College of Cardinals assumes limited authority and manages the Church’s day-to-day matters.

The conclave to elect the new pope typically begins 15 to 20 days after the pope’s death, following the period of mourning. In the case of papal resignation, as with Benedict XVI in 2013, similar procedures apply.

Before the conclave, the cardinals attend two sermons that outline the Church’s current state and the qualities needed in a new pope. On the designated day, they celebrate Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica and proceed to the Sistine Chapel, where they take an oath of secrecy and adherence to the election rules.

After the oath, all non-participants are ordered to leave the chapel.

The conclave’s strict secrecy is enforced, with severe penalties for breaches. All electronic communication is blocked to prevent external interference.

Cardinals receive ballot cards and vote in the Sistine Chapel, with up to four ballots held daily. A two-thirds majority is required for election, and if a result is not reached, a runoff occurs between the top two candidates.

The ballots are then burned, with white smoke indicating a successful election and black smoke signalling no decision.

External influences

Secular rulers heavily influenced papal elections for much of the Church’s history. The Holy Roman Empire asserted control in the 9th century. From the 17th century, some Catholic monarchs held a veto power, used for the last time in 1903, when Pope Pius X banned government interference.

Despite this controlled environment, the world of politics, friendships and alliances, and the personal ambitions of the cardinals shape the outcome.

The conclave not only serves as a means of selecting the leader of the Catholic Church, but also reflects broader power dynamics within and beyond the Vatican.

Darius von Guttner Sporzynski does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.